Transition metal

The 2011 IUPAC Principles of Chemical Nomenclature describe a "transition metal" as any element in groups 3 to 12 on the periodic table.

[7] The IUPAC Gold Book[8] defines a transition metal as "an element whose atom has a partially filled d sub-shell, or which can give rise to cations with an incomplete d sub-shell", but this definition is taken from an old edition of the Red Book and is no longer present in the current edition.

Published texts and periodic tables show variation regarding the heavier members of group 3.

[9] The common placement of lanthanum and actinium in these positions is not supported by physical, chemical, and electronic evidence,[10][11][12] which overwhelmingly favour putting lutetium and lawrencium in those places.

[13][14] Some authors prefer to leave the spaces below yttrium blank as a third option, but there is confusion on whether this format implies that group 3 contains only scandium and yttrium, or if it also contains all the lanthanides and actinides;[15][16][17][18][19] additionally, it creates a 15-element-wide f-block, when quantum mechanics dictates that the f-block should only be 14 elements wide.

[15] The form with lutetium and lawrencium in group 3 is supported by a 1988 IUPAC report on physical, chemical, and electronic grounds,[20] and again by a 2021 IUPAC preliminary report as it is the only form that allows simultaneous (1) preservation of the sequence of increasing atomic numbers, (2) a 14-element-wide f-block, and (3) avoidance of the split in the d-block.

[15] Argumentation can still be found in the contemporary literature purporting to defend the form with lanthanum and actinium in group 3, but many authors consider it to be logically inconsistent (a particular point of contention being the differing treatment of actinium and thorium, which both can use 5f as a valence orbital but have no 5f occupancy as single atoms);[14][21][22] the majority of investigators considering the problem agree with the updated form with lutetium and lawrencium.

The group 12 elements Zn, Cd and Hg may therefore, under certain criteria, be classed as post-transition metals in this case.

Moreover, Zn, Cd, and Hg can use their d orbitals for bonding even though they are not known in oxidation states that would formally require breaking open the d-subshell, which sets them apart from the p-block elements.

Although meitnerium, darmstadtium, and roentgenium are within the d-block and are expected to behave as transition metals analogous to their lighter congeners iridium, platinum, and gold, this has not yet been experimentally confirmed.

The p orbitals are almost never filled in free atoms (the one exception being lawrencium due to relativistic effects that become important at such high Z), but they can contribute to the chemical bonding in transition metal compounds.

The typical electronic structure of transition metal atoms is then written as [noble gas]ns2(n − 1)dm.

For Cr as an example the rule predicts the configuration 3d44s2, but the observed atomic spectra show that the real ground state is 3d54s1.

[32] The (n − 1)d orbitals that are involved in the transition metals are very significant because they influence such properties as magnetic character, variable oxidation states, formation of coloured compounds etc.

The valence s and p orbitals (ns and np) have very little contribution in this regard since they hardly change in the moving from left to the right in a transition series.

[34] Colour in transition-series metal compounds is generally due to electronic transitions of two principal types.

A metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) transition will be most likely when the metal is in a low oxidation state and the ligand is easily reduced.

The molar absorptivity (ε) of bands caused by d–d transitions are relatively low, roughly in the range 5-500 M−1cm−1 (where M = mol dm−3).

[36] Gallium also has a formal oxidation state of +2 in dimeric compounds, such as [Ga2Cl6]2−, which contain a Ga-Ga bond formed from the unpaired electron on each Ga atom.

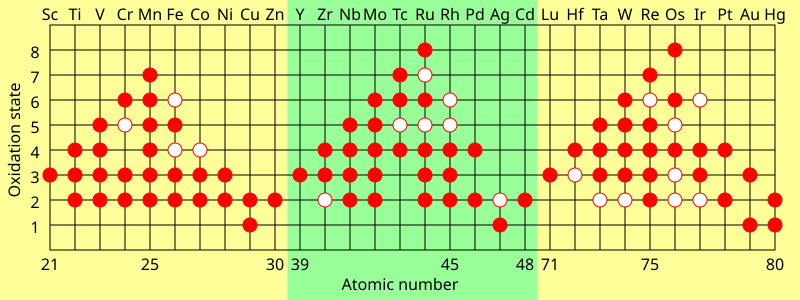

The maximum oxidation state in the first row transition metals is equal to the number of valence electrons from titanium (+4) up to manganese (+7), but decreases in the later elements.

Ferromagnetism occurs when individual atoms are paramagnetic and the spin vectors are aligned parallel to each other in a crystalline material.

Antiferromagnetism is another example of a magnetic property arising from a particular alignment of individual spins in the solid state.

This has the effect of increasing the concentration of the reactants at the catalyst surface and also weakening of the bonds in the reacting molecules (the activation energy is lowered).

3 )

2 (red); K

2 Cr

2 O

7 (orange); K

2 CrO

4 (yellow); NiCl

2 (turquoise); CuSO

4 (blue); KMnO

4 (purple).