Translation (biology)

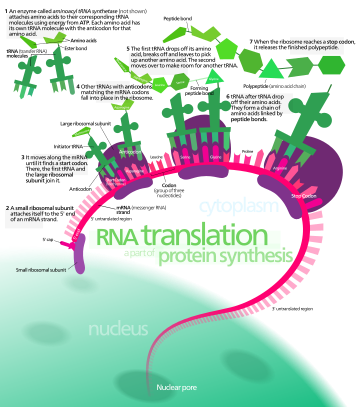

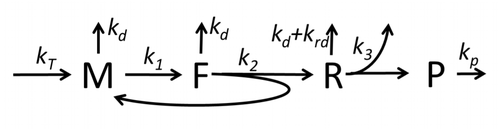

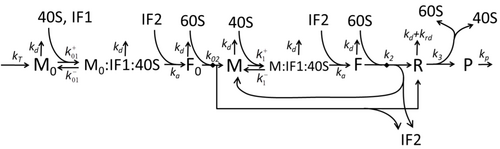

In biology, translation is the process in living cells in which proteins are produced using RNA molecules as templates.

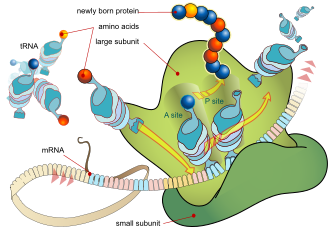

In translation, messenger RNA (mRNA) is decoded in a ribosome, outside the nucleus, to produce a specific amino acid chain, or polypeptide.

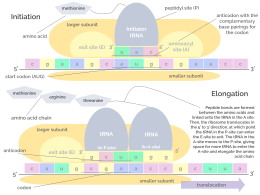

[1] The ribosome facilitates decoding by inducing the binding of complementary transfer RNA (tRNA) anticodon sequences to mRNA codons.

The tRNAs carry specific amino acids that are chained together into a polypeptide as the mRNA passes through and is "read" by the ribosome.

In eukaryotes, translation occurs in the cytoplasm or across the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum through a process called co-translational translocation.

[3] The choice of amino acid type to add is determined by a messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule.

[citation needed] The ribosome molecules translate this code to a specific sequence of amino acids.

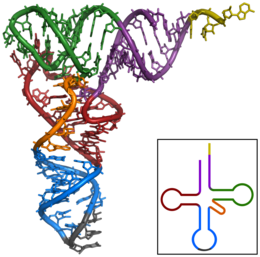

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are small noncoding RNA chains (74–93 nucleotides) that transport amino acids to the ribosome.

Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases (enzymes) catalyze the bonding between specific tRNAs and the amino acids that their anticodon sequences call for.

In bacteria, this aminoacyl-tRNA is carried to the ribosome by EF-Tu, where mRNA codons are matched through complementary base pairing to specific tRNA anticodons.

This "mistranslation"[7] of the genetic code naturally occurs at low levels in most organisms, but certain cellular environments cause an increase in permissive mRNA decoding, sometimes to the benefit of the cell.

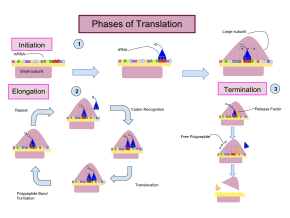

The binding of these complementary sequences ensures that the 30S ribosomal subunit is bound to the mRNA and is aligned such that the initiation codon is placed in the 30S portion of the P-site.

[11] Termination of the polypeptide occurs when the A site of the ribosome is occupied by a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA) on the mRNA, creating the primary structure of a protein.

Instead, the stop codon induces the binding of a release factor protein[12] (RF1 & RF2) that prompts the disassembly of the entire ribosome/mRNA complex by the hydrolysis of the polypeptide chain from the peptidyl transferase center [2] of the ribosome.

[13] Drugs or special sequence motifs on the mRNA can change the ribosomal structure so that near-cognate tRNAs are bound to the stop codon instead of the release factors.

[14] Even though the ribosomes are usually considered accurate and processive machines, the translation process is subject to errors that can lead either to the synthesis of erroneous proteins or to the premature abandonment of translation, either because a tRNA couples to a wrong codon or because a tRNA is coupled to the wrong amino acid.

[15] The rate of error in synthesizing proteins has been estimated to be between 1 in 105 and 1 in 103 misincorporated amino acids, depending on the experimental conditions.

Regulation of translation can impact the global rate of protein synthesis which is closely coupled to the metabolic and proliferative state of a cell.

To study this process, scientists have used a wide variety of methods such as structural biology, analytical chemistry (mass-spectrometry based), imaging of reporter mRNA translation (in which the translation of a mRNA is linked to an output, such as luminescence or fluorescence), and next-generation sequencing based methods.

For example, research utilizing this method has revealed that genetic differences and their subsequent expression as mRNAs can also impact translation rate in an RNA-specific manner.

[21] Expanding on this concept, a more recent development is single-cell ribosome profiling, a technique that allows us to study the translation process at the resolution of individual cells.

It is also possible to translate either by hand (for short sequences) or by computer (after first programming one appropriately, see section below); this allows biologists and chemists to draw out the chemical structure of the encoded protein on paper.

This approach may not give the correct amino acid composition of the protein, in particular if unconventional amino acids such as selenocysteine are incorporated into the protein, which is coded for by a conventional stop codon in combination with a downstream hairpin (SElenoCysteine Insertion Sequence, or SECIS).

Normally this is performed using the Standard Genetic Code, however, few programs can handle all the "special" cases, such as the use of the alternative initiation codons which are biologically significant.