Transposing instrument

Before valves were invented in the 19th century, horns and trumpets could play only the notes of the overtone series from a single fundamental pitch.

Medial crooks, inserted in the central portion of the instrument, were an improvement devised in the middle of the 18th century, and they could also be made to function as a slide for tuning, or to change the pitch of the fundamental by a semitone or tone.

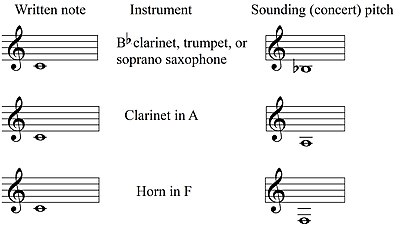

F transposition became standard in the early 19th century, with the horn sounding a perfect fifth below written pitch in treble clef.

Modern builders of continuo instruments sometimes include moveable keyboards which can play with either pitch standard.

[2] Some harpsichords are made with a mechanism that shifts the keyboard action right or left, causing each key to play the adjacent string.

The top or bottom key on the instrument will not produce sound unless the builder has added extra strings to accommodate this transposition.

In order to avoid the use of excessive ledger lines, music for these instruments may be written one, or even two, octaves away from concert pitch, using treble or bass clef.

Piccolo, xylophone, celesta, and some recorders (sopranino, soprano, bass and sometimes alto) sound an octave above the written note.

Most woodwind instruments have one major scale whose execution involves lifting the fingers more or less sequentially from bottom to top.

This convention is not followed in British Brass Band music, where tenor trombone is treated as a transposing instrument in B♭.