Treaty of Devol

The Treaty of Deabolis (Greek: συνθήκη της Δεαβόλεως) was an agreement made in 1108 between Bohemond I of Antioch and Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, in the wake of the First Crusade.

Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, who had requested only some western knights to serve as mercenaries to help fight the Seljuk Turks, blockaded these armies in the city and would not permit them to leave until their leaders swore oaths promising to restore to the Empire any land formerly belonging to it that they might conquer on the way to Jerusalem.

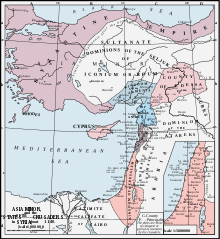

[3] The crusaders, feeling betrayed by Alexios, who was able to recover a number of important cities and islands, and in fact much of western Asia Minor, continued on their way without Byzantine aid.

In 1098, when Antioch had been captured after a long siege and the crusaders were in turn themselves besieged in the city, Alexios marched out to meet them, but, hearing from Stephen of Blois that the situation was hopeless, he returned to Constantinople.

In 1107, having organized a new army for his planned crusade against the Muslims in Syria, Bohemond instead launched into open warfare against Alexios, crossing the Adriatic to lay siege to Dyrrhachium, the westernmost city of the Empire.

[14] Bohemond soon found himself in an impossible position, isolated in front of Dyrrhachium: his escape by sea was cut off by the Venetians, and Paschal II withdrew his support.

[17] The specific terms of the treaty were negotiated by the general Nikephoros Bryennios, and were recorded by Anna Komnene:[18] The terms were negotiated according to Bohemond's western understanding, so that he saw himself as a feudal vassal of Alexios, a "liege man" (homo ligius or ἄνθρωπος λίζιος) with all the obligations this implied, as customary in the West: he was obliged to bring military assistance to the Emperor, except in wars in which he was involved, and to serve him against all his enemies, in Europe and in Asia.

From Alexios' imperial court, the treaty was witnessed by the sebastos Marinos of Naples, Roger son of Dagobert, Peter Aliphas, William of Gand, Richard of the Principate, Geoffrey of Mailli, Hubert son of Raoul, Paul the Roman, envoys from the Queen's relation (from the family of the former cral/king of Bulgaria), the ambassadors Peres and Simon from Hungary, and the ambassadors Basil the Eunuch and Constantine.

[24] Many of Alexios' witnesses were themselves Westerners, who held high positions in the Byzantine army and at the imperial court;[25] Basil and Constantine were ambassadors in the service of Bohemond's relatives in Sicily.

[27] Alexios, recognizing the impossibility of driving Bohemond out of Antioch, tried to absorb him into the structure of Byzantine rule, and put him to work for the Empire's benefit.

[28] Bohemond was to retain Antioch until his death with the title of doux, unless the emperor (either Alexios or, in the future, John) chose for any reason to renege on the deal.

Bohemond therefore could not set up a dynasty in Antioch, although he was guaranteed the right to pass on to his heirs the County of Edessa, and any other territories he managed to acquire in the Syrian interior.

[29] René Grousset calls the Treaty a "Diktat", but Jean Richard underscores that the rules of feudal law to which Bohemond had to submit "were in no way humiliating.

"[22] According to John W. Birkenmeier, the Treaty marked the point at which Alexios had developed a new army, and new tactical doctrines with which to use it, but it was not a Byzantine political success; "it traded Bohemond's freedom for a titular overlordship of Southern Italy that could never be effective, and for an occupation of Antioch that could never be carried out.

[32] In contrast, Asbridge has recently argued that the Treaty derived from Greek as well as western precedents, and that Alexios wished to regard Antioch as falling under the umbrella of pronoia arrangements.

Although the Treaty of Deabolis never came into effect, it provided the legal basis for Byzantine negotiations with the crusaders for the next thirty years, and for imperial claims to Antioch during the reigns of John II and Manuel I.

[37] The campaign finally failed, however, partly because Raymond and Joscelin II, Count of Edessa, who had been obliged to join John as his vassals, did not pull their weight.

[42] Antioch, weakened by powerless regents after Raynald's capture by the Muslims in 1160, remained a Byzantine vassal state until 1182 when internal divisions following Manuel's death in 1180 hindered the Empire's ability to enforce its claim.