Treaty of Naples (1639)

[1] Politically the two countries operated in entirely different zones; the former focused on the Iberian Peninsula, western/central Mediterranean and northern slopes of the Pyrenees, the latter concentrated on the Baltic and huge plains in the Oder-Vistula-Dnieper basins.

In the mid-1620s Felipe IV of Spain intended to crack down on Dutch merchant shipping on northern routes,[6] while Sigismund III of Poland, himself of Swedish origin, had his eyes set on regaining the throne in Stockholm.

[10] Apart from usual negotiations on the Sforza heritage, the talks focused on compensation for the Polish fleet lost to the Swedes when nominally at the service of Felipe IV and ensuring Spanish posts and pension for two royal brothers.

Though the agreement sealed some heritage and succession issues and did not cover military co-operation, it seemed that following years of indecision, the king of Poland was firmly leaning towards Vienna instead of Paris.

In early 1638 prince John Casimir left Poland for Spain; it is not entirely clear whether Madrid and Warsaw had agreed on his future role on the Iberian Peninsula or whether he travelled to speed negotiations up.

During his stay in Vienna the Paris press broke the news on his future appointment as viceroy of Portugal; Spanish sources suggest it was merely an option, considered at Consejo de Estado.

[22] Officially he was charged with espionage,[23] but scholars speculate that cardinal Richelieu seized the opportunity to dissuade Władysław IV from military alliance with the Habsburgs and from entering the Thirty Years' War.

In October 1638 Władysław met Ferdinand III in Nikolsburg to agree further action; both monarchs decided to seek mediation of Italian states, usually on good terms with the king of France.

He arrived in Warsaw in the spring of 1639 and found Władysław IV not only upset with the French and frustrated with futile Italian mediation, but also adopting an increasingly belligerent attitude.

[31] Details of Monroy's talks in Poland are not known and it is not clear who he spoke to, yet the key of his partners was Adam Kazanowski, personal friend of the king[32] and high official at the court.

[33] During or shortly after Monroy's mission the Polish king decided to explore the path proposed by Madrid and to start talks on military co-operation, potentially aimed against the French.

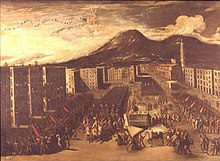

[37] It is not exactly clear why Naples and Medina have been chosen; Vienna would have been closer and the Spanish diplomatic team there, especially marqués de Castañeda, were better acquainted with details of East European policy.

Scholars speculate that at the time the Kingdom of Naples turned into sort of a logistics base and reserve economic pool for Madrid, and Medina was well experienced in handling related financial issues.

Some viewed them as brutal and hard to control; the Elector of Saxony claimed that cossack mercenaries in Polish service were “harmful people that do as much damage to enemies as to friends”.

He might have considered minor engagement if this would enhance his position against the competitive Vasa branch ruling in Sweden, but he was generally unwilling to commit himself either to the Spanish-Austrian alliance or to the French; his strategy consisted of leaving all options open.

However, it is not clear whether he genuinely considered a Polish army to be engaged against the French, or whether from the onset he approached his talks with the Spaniards merely as a diplomatic means against Paris, and was never willing to close a deal with Madrid.

[49] Another possible option was that objectives of Władysław IV were purely financial, and that dependent upon the diet when it comes to raising money internally, he intended to extract cash from the Madrid court.

Finally, an Italian in Spanish diplomatic service, a certain Allegretto de Allegretti, who for some time has been serving as a link between the Vienna embassy and Warsaw, was to supervise recruitment and organization of the troops in Poland.

[65] In the spring a Polish mission in Paris secured liberation of Jan Kazimierz following 2 years in custody; in return, the Vasas pledged not to engage militarily against the French.

In late spring Madrid decided to send to Poland a military who would professionally assess the state of affairs; the person chosen was Pedro Roco de Villagutiérrez, cavalry captain at the service of Cardenal Infante in Flanders.

Finally, numerous details were added to specify issues such as command, transport and logistics,[88] e.g. Medina successfully resisted the demand that the troops be entitled to plunder territories they pass through.

The person chosen was Vicenzo Tuttavilla, duca de Calabritto,[92] a military man who later grew to high commander in the army of the Kingdom of Naples.

[93] When Tuttavilla arrived in Warsaw in the spring of 1641 he found himself engaged in diplomatic struggle against a team of French envoys, who worked to prevent the Vasa rapprochement with the Habsburgs and ensure Polish neutrality in the Thirty Years' War.

[94] Kazanowski, who by the time has pocketed large sums from the Spaniards and was personally implicated in the deal, maintained that there was a high chance of success; in early autumn of 1641 he claimed having support of 48 senators with only few more needed to be won over.

[96] In late 1641 the emperor Ferdinand III declared that no Polish army would be allowed to pass through his lands; Madrid sent Marqués de Castelo Rodrigo to Vienna to negotiate, but the envoy was only treated to suggestions that the entire deal be abandoned, with cheaper recruitment options in Denmark or Silesia.

[97] The position of Medina himself, the chief negotiator of the deal, was also becoming fragile; his political ally Cardinal Infante passed away and he was left relying solely on his family relation to Olivares.

Medina was very critical about Castañeda and claimed the Vienna ambassador mishandled his mission, namely that appointment of Allegretti allowed the Poles to believe the treaty was negotiable.

[106] Another factor listed as contributing to failure was position adopted by the emperor; always skeptical about transit of the Poles across his territory; in key moments he refused the right of passage and effectively buried the project.

[108] Polish historians have doubts about intentions of Władysław IV and suspect that he might have engaged in negotiations with the Spaniards with ill will, using them as an instrument enabling him to exert some pressure on the French.

The Polish light cavalry formation known as lisowczycy, at times confused with cossacks, was briefly engaged in 1620 fighting in Upper Hungary; it achieved some success against Protestant troops, but gained opinion of an army that “God would not want and the devil would be afraid of”,[112] which made its further employment doubtful.