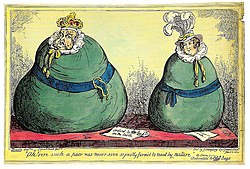

Pains and Penalties Bill 1820

After a sensational debate in the Lords, which was heavily reported in the press in salacious detail, the bill was narrowly passed by the upper house.

However, George IV refused to recognise Caroline as queen, and commanded British ambassadors to ensure that monarchs in foreign courts did the same.

In June, Caroline returned to London to assert her rights as queen consort of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

George despised her, and over the preceding few years had collected evidence to support his contention that Caroline had committed adultery while abroad with Bartolomeo Pergami, the head servant of her household.

Brougham was in the opposition Whig party and knew that public sympathy rested with Caroline, rather than her husband or the government, which was weak and unpopular.

Disclosure of George's own adulterous affairs, or even his scandalous and unlawful previous marriage to Maria Fitzherbert, could destabilise the Tory government led by Lord Liverpool.

[4] Wilberforce moved a motion in the House of Commons requesting that Caroline not insist on all her claims, which was passed by a wide margin of 394 votes to 124.

His eldest son had recently died and, rather than be involved in the debate, Canning left Britain on a tour of Europe to recover from his grief.

The bill charged that Caroline had committed adultery with Bartolomeo Pergami, "a foreigner of low station", and that consequently she had forfeited her rights to be queen consort.

[14] By August, Caroline had allied with radical campaigners such as William Cobbett, and it was probably Cobbett who wrote these words of Caroline's:[15] If the highest subject in the realm can be deprived of her rank and title—can be divorced, dethroned and debased by an act of arbitrary power, in the form of a Bill of Pains and Penalties—the constitutional liberty of the Kingdom will be shaken to its very base; the rights of the nation will be only a scattered wreck; and this once free people, like the meanest of slaves, must submit to the lash of an insolent domination.

In it, she decried the injustices against her, claimed she was the victim of conspiracy and intrigue, accused George of heartlessness and cruelty, and demanded a fair trial.

[22] In their speeches, Brougham and Denman hinted but did not state explicitly, referring only to "recrimination", that George could come off worse because of the bill if his own infidelities (such as his secret marriage to Maria Fitzherbert) were revealed in the course of the debate.

[23] The prosecution case, led by the Attorney General for England and Wales Sir Robert Gifford, began on Saturday 19 August.

By forcing the details of Caroline's life into the public arena, George had damaged the monarchy and endangered the political status quo.

[37] Under examination by the Solicitor General for England and Wales, John Singleton Copley, Majocchi testified that Caroline and Pergami ate breakfast together, had adjoining bedrooms, and had kissed each other on the lips.

[45] After the conclusion of the cross-examination, however, Lord Ellenborough rose and asked Briggs directly, "Did the witness see any improper familiarity between the Princess and Pergami?

[44] A further witness, Pietro Cuchi, an innkeeper in Trieste, told the Lords that he had spied on the couple through a keyhole, during which he thought he saw Pergami leave the Queen's bedroom wearing stockings, pantaloons and a dressing gown.

[52] The procession of witnesses continued; a mason, Luigi Galdini, claimed he had stumbled across Pergami holding Caroline's bare breast in their Italian villa.

[36] Coachman Giuseppe Sacchi, who was Demont's lover,[53] claimed that he had found the couple asleep in a carriage in each other's arms, with Caroline's hand on Pergami's undone breeches.

[54] Sacchi's testimony was ridiculed in the British press, as "the parties being asleep, such a position in a carriage, where the bodies are themselves upright, or nearly so, is beyond all question absolutely and physically impossible".

[57] Liverpool warned the King that Majocchi and Demont were discredited as witnesses, and the evidence produced by the defence could damage George severely.

[56] After the presentation of the prosecution case, the trial was adjourned for three weeks, and the Queen's solicitor, Denman, visited Cheltenham Spa for a break.

"[67] He reminded the Lords that Majocchi was forgetful, that Demont was a liar, and that Cuchi was a lecherous wretch who spied on his female guests through a keyhole.

Keppel Craven, Sir William Gell, Henry Holland, Colonel Alessandro Olivieri, and Carlo Vassalli, all of whom swore that there was nothing unusual about Caroline's behaviour.

[71] Under cross-examination, Lord Guilford was unable to recall leaving a handsome Greek servant alone with Caroline for three-quarters of an hour,[72] and Lady Charlotte had on occasion said "I do not recollect", but without the same disdain that had met Majocchi's constant refrain of non mi ricordo.

[74] A French milliner, Fanchette Martigner, further testified that Demont had told her that Caroline was innocent, and the charges against her "were nothing but calumnies invented by her enemies in order to ruin her".

[79] The Whigs now claimed that the trial was tainted as there was prima facie evidence of conspiracy to pervert the course of justice by paying witnesses for their testimony.

[81] The Tories challenged Brougham's line of questioning, as they claimed it implicated persons who could not be called as witnesses, and widened the investigation beyond the relevance of the bill.

Even if Caroline had shown Pergami favour, it was within the power of royalty to elevate anyone from a low rank to a high one, and it was a strength of society that any person could rise from the lowest of births to the highest of offices.

They had travelled through countries that through the influence of the French Revolution had seen the reversal of traditional power structures, with the once-wealthy laid low, and the obscure propelled to distinction.