Tribal Hidage

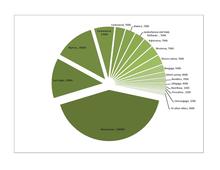

The list is headed by Mercia and consists almost exclusively of peoples who lived south of the Humber estuary and territories that surrounded the Mercian kingdom, some of which have never been satisfactorily identified by scholars.

The Tribal Hidage has been used to construct theories about the political organisation of the Anglo-Saxons, and to give an insight into the Mercian state and its neighbours when Mercia held hegemony over them.

The Tribal Hidage is, according to historian D. P. Kirby, "a list of total assessments in terms of hides for a number of territories south of the Humber, which has been variously dated from the mid-7th to the second half of the 8th century".

Other named tribes have even smaller hidages, of between 300 and 1200 hides: of these the Herefinna, Noxgaga, Hendrica and Unecungaga cannot be identified,[5] whilst the others have been tentatively located around the south of England and in the border region between Mercia and East Anglia.

[12] Frank Stenton describes the hidage figures given for the Heptarchy kingdoms as exaggerated and in the instances of Mercia and Wessex, "entirely at variance with other information".

[20] Other historians, such as J. Brownbill, Barbara Yorke, Frank Stenton and Cyril Roy Hart, have written that it originated from Mercia at around this time, but differ on the identity of the Mercian ruler under whom the list was compiled.

[24][25] N. J. Higham has argued that because the original information cannot be dated and the largest Northumbrian kingdoms are not included, it cannot be proved to be a Mercian tribute list.

He notes that Elmet, never a province of Mercia, is on the list,[26] and suggests that it was drawn up by Edwin of Northumbria in the 620s,[27] probably originating when a Northumbrian king last exercised imperium over the Southumbrian kingdoms.

[33] James Campbell has argued that if the list served any practical purpose, it implies that tributes were assessed and obtained in an organised way,[20] and notes that, "whatever it is, and whatever it means, it indicates a degree of orderliness, or coherence in the exercise of power...".

Among these, the Isle of Wight and the South Gyrwe tribes, tiny in terms of their hidages and geographically isolated from other peoples, were among the few who possessed their own royal dynasties.

To Sawyer, the obscurity of some of the tribal names and the absence from the list of others points to an early date for the original text, which he describes as a "monument to Mercian power".

[36] Of the first or primary part of the list contained several recognized peoples: This part of the list seems to have been added: Sir Henry Spelman was the first to publish the Tribal Hidage in his first volume of Glossarium Archaiologicum (1626) and there is also a version of the text in a book written in 1691 by Thomas Gale, but no actual discussion of the Tribal Hidage emerged until 1848, when John Mitchell Kemble's The Saxons in England was published.

[31] In 1884, Walter de Gray Birch wrote a paper for the British Archaeological Association, in which he discussed in detail the location of each of the tribes.

[38] The most important subsequent accounts of the Tribal Hidage since Corbett, according to Campbell, are by Josiah Cox Russell (1947), Hart (1971), Davies and Vierck (1974) and David Dumville (1989).

[39] Kemble recognised the antiquity of Spelman's document and used historical texts (such as Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum) to assess its date of origin.

[42] He methodically compared all the publications and manuscripts of the Tribal Hidage that are available at the time and placed each tribe using both his own theories and the ideas of others, some of which (for instance when he located the Wokensætna in Woking, Surrey) are now discounted.

Assuming that all the English south of the Humber are listed within the Tribal Hidage, he produced a map that divides southern England into Mercia's provinces and outlying dependencies, using evidence from river boundaries and other topographical features, place-names and historical borders.

[31] The Tribal Hidage lists several minor kingdoms and tribes that are not recorded anywhere else[14] and is generally agreed to be the earliest fiscal document that has survived from medieval England.

The expansion of Wessex in the tenth century would have caused the obliteration of the Middle Anglia's old divisions,[52] by which time the places listed would have become mere names.

[59] Scott DeGregorio has argued that the Tribal Hidage provides evidence that Anglo-Saxon governments required a system of "detailed assessment" in order to construct great earthworks such as Offa's Dyke.

[60] According to Davies and Vierck, 7th century East Anglia may have consisted of a collection of regional groups, some of which retained their individual identity.