Trichome

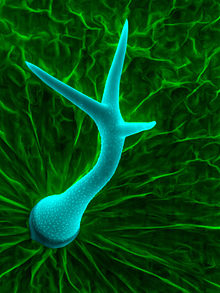

Trichomes (/ˈtraɪkoʊmz, ˈtrɪkoʊmz/; from Ancient Greek τρίχωμα (tríkhōma) 'hair') are fine outgrowths or appendages on plants, algae, lichens, and certain protists.

Certain, usually filamentous, algae have the terminal cell produced into an elongate hair-like structure called a trichome.

[citation needed] The filamentous sheaths form a persistent sticky network that helps maintain soil structure.

[4] Trichomes can protect the plant from a large range of detriments, such as UV light, insects, transpiration, and freeze intolerance.

Branched hairs can be dendritic (tree-like) as in kangaroo paw (Anigozanthos), tufted, or stellate (star-shaped), as in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Another common type of trichome is the scale or peltate hair, that has a plate or shield-shaped cluster of cells attached directly to the surface or borne on a stalk of some kind.

Common examples are the leaf scales of bromeliads such as the pineapple, Rhododendron and sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides).

In windy locations, hairs break up the flow of air across the plant surface, reducing transpiration.

Dense coatings of hairs reflect sunlight, protecting the more delicate tissues underneath in hot, dry, open habitats.

In addition, in locations where much of the available moisture comes from fog drip, hairs appear to enhance this process by increasing the surface area on which water droplets can accumulate.

[9] For example, the model plant C. salviifolius is found in areas of high-light stress and poor soil conditions, along the Mediterranean coasts.

It contains non-glandular, stellate and dendritic trichomes that have the ability to synthesize and store polyphenols that both affect absorbance of radiation and plant desiccation.

[4] In Salix and gossypium genus, modified trichomes create the cottony fibers that allow anemochory, or wind aided dispersal.

[4] Both trichomes and root hairs, the rhizoids of many vascular plants, are lateral outgrowths of a single cell of the epidermal layer.

Both processes involve a core of related transcription factors that control the initiation and development of the epidermal outgrowth.

Activation of genes that encode specific protein transcription factors (named GLABRA1 (GL1), GLABRA3 (GL3) and TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 (TTG1)) are the major regulators of cell fate to produce trichomes or root hairs.

[22] Trichomes are an essential part of nest building for the European wool carder bee (Anthidium manicatum).

In Urtica, the stinging trichomes induce a painful sensation lasting for hours upon human contact.

Studies suggest that this sensation involves a rapid release of toxin (such as histamine) upon contact and penetration via the globular tips of said trichomes.