Trikaya

[1] This concept posits that a Buddha has three distinct "bodies", aspects, or ways of being, each representing a different facet or embodiment of Buddhahood and ultimate reality.

It is widely accepted in Mahayana that these three bodies are not separate realities, but functions, modes or "fluctuations" (Sanskrit: vṛṭṭis) of a single state of Buddhahood.

It is also used to explain the Mahayana doctrine of non-abiding nirvana (apratiṣṭhita-nirvana), which sees Buddhahood as both unconstructed (asaṃskṛta) and transcendent, as well as constructed, immanent and active in the world.

Thus, the Madhyāntavibhāga says of Buddhahood "Its operation is nondual (advaya vṛtti) because of its abiding neither in saṃsāra nor in nirvāṇa (saṃsāra-nirvāṇa-apratiṣṭhitatvāt), through its being both conditioned and unconditioned (saṃskṛta-asaṃskṛtatvena).

Likewise, within the purified dharma realm (dharmadhātuviśuddha) of the Tathagatas, there appear the arising and ceasing of awareness, manifestation, and performance of all the activities for sentient beings.

[9] The Trikāyasūtra preserved in the Tibetan canon contains the following simile for the three bodies:the dharmakāya of the Tathāgata consists in the fact that he has no nature, just like the sky.

[25] Because of this negative buddhology that is often used to describe the Dharmakaya, it is often depicted with impersonal symbols, like the letter A, some other mantric seed syllable, the disk of the moon or sun, space (Sanskrit: ākāśa), or the sky (gagana).

According to Williams, Yogācāra sees the Dharmakāya as the support or basis of all dharmas, and as being a self-contained nature (svabhāva) which lacks anything contingent or adventitious.

[9] [31] In the Xuanzang's Chengweishilun (Treatise Demonstrating Consciousness-only), the Dharmakaya (also called here the vimuktikaya, body of liberation) is described as what is adorned with the great Buddha qualities (mahāguṇa), which are conditioned and unconditioned, immeasurable, and infinite.

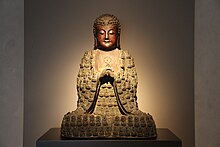

[20] This body is the object of popular Buddhist devotion in Mahayana Buddhism, it is the Buddha as an omniscient transcendent being with immense powers, animated only by universal compassion for all living things.

Likewise, it is agreed, its activity (karman) is uninterrupted for as long as cyclic existence last... (AA 8.33) [48]Manifestation bodies allow Buddhas to interact with and teach sentient beings in a more direct and human manner.

[49] Xuanzang's Chengweishilun defines the emanation body as the method used by Buddhas through their knowledge of accomplishing actions (kṛṭya-anuṣṭhāna-jñāna) to create "innmumerable and varied" transformations "which inhabit pure or impure lands".

[56] Furthermore, in Abhidharma texts like the Abhidharmakośa and the Mahāvibhāṣa Śāstra, dharmakaya also includes the eighteen special qualities of a Buddha (āveṇikadharmaḥ), which are: the ten powers, four forms of fearlessness, great compassion, and the three mindful equanimities.

[61] In another passage, the Aṣṭasāhasrikā identifies the Buddha with the real nature, dharmataya, which is unmoving, non-arising (anutpada), emptiness, the thusness of dharmas (dharmam tathātā) which has no enumeration or division.

The dharmakāya has [the attributes of ] eternity (nitya), happiness (sukha), self (ātman) and purity (śubha) and is perpetually free from birth, old age, sickness, death and all other sufferings .

[77] By the time the mature Sambhogakāya concept was developed in the Yogacara treatises, it had absorbed all the various transcendent qualities that had been attributed to the Buddha in the Mahayana sutras, such as his boundless light, limitless life-span and power.

[85] The term "fundamental transformation" or "revolution of the basis" (āśraya-parāvṛtti) indicates that the a key element of Buddhahood's essence is its aspect as a totally purified and perfected (paranispanna) nature, i.e. the Buddha's non-dual knowledge (which transcends any sense of self, or of subject and object).

[87] Furthermore, according to Makransky, in this early formulation, there are not really three different "bodies", instead there is ultimately one "insubstantial, unlimited, and undivided" purified dharma realm that all Buddhas share and which is embodied in three modes.

Meanwhile, the jñānātmaka-dharmakāya was "the conditioned aspect through which he appears to beings within their world of delusion to work for them", in other words, the Buddha wisdom (buddhajñāna) and undefiled dharmas, which are still impermanent and relative.

[94] Furthermore, as Makransky writes, for Haribhadra the Yogacara model gave rise to a logical tension because it failed to distinguish separate ontological bases for the transcendence and immanence of Buddhahood.

A more accurate interpretation of the Abhisamayalankara's eighth chapter, according to Makransky, is Arya Vimuktisena's three kaya view, since it matches a straightforward and historical reading of the text as a Yogacara work.

[99] As such, the logical tension found in the teaching of the dharmakaya as being immanent and transcendent at the same time is a key element of the three body theory which challenges us to attain that non-dual state of non-abiding nirvana.

[91] In Tibetan Buddhism, one common meaning of the fourth body, the svābhāvikakāya (when understood as a different concept than dharmakāya), is that it is refers to the inseparability and identity of all three kāyas.

For example, the Dharmakāya in the Chinese Esoteric Buddhist and Huayan traditions is often understood through the cosmic body of Mahavairocana, which consists of the whole cosmos and also is the basis for all reality, the ultimate principle (li, 理), equivalent to the One Mind taught in the Awakening of Faith.

This is explained by the Japanese Shingon founder Kukai in his Difference between exoteric and esoteric (Benkenmitsu nikyoron) which says that mikkyo is taught by the cosmic embodiment (hosshin) Buddha.

[115] Simmer-Brown (2001: p. 334) asserts that: When informed by tantric views of embodiment, the physical body is understood as a sacred maṇḍala (Wylie: lus kyi dkyil).

Understanding this fundamental nature, you give up the three kinds of physical activity--good, bad, and neutral--and sit like a corpse in a charnal ground, with nothing needing to be done.

The literature of this school, such as the Tao-chiao i-shu (Pivotal Meaning of the Taoist Teaching) by Meng An-p’ai, is heavily influenced by Buddhist terminology.

[130] According to Sharf, the Tao-chiao i-shu presents a Daoist triple body theory (sanshen 三身) based on an ultimate “law-body” (fa-shen, 法身, the same Chinese characters used in Buddhism for Dharmakaya), which is a "fundamental principle on which all is “modeled” (fa); it is also used to refer to the Taoist deity the Heavenly Venerable (t’ien-tsun).

[20] A major difference with these other systems however, is that Buddhism rejects the concept of a Creator Deity or Ishvara (supreme lord) who is the controller of karma and reincarnation.