Apophatic theology

[web 2]According to Fagenblat, "negative theology is as old as philosophy itself:" elements of it can be found in Plato's unwritten doctrines, while it is also present in Neo-Platonic, Gnostic and early Christian writers.

[3] According to Carabine, "apophasis proper" in Greek thought starts with Neo-Platonism, with its speculations about the nature of the One, culminating in the works of Proclus.

"[15] Plato (428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC), "deciding for Parmenides against Heraclitus" and his theory of eternal change,[16] had a strong influence on the development of apophatic thought.

[16] The Theory of Forms is Plato's answer to the problem of how one fundamental reality or unchanging essence can admit of many changing phenomena, other than by dismissing them as being mere illusion.

[18][web 5] Humans are to be educated to search for knowledge, by turning away from their bodily desires toward higher contemplation, culminating in an intellectual[note 5] understanding or apprehension of the Forms, c.q.

"[18] According to Cook, the Theory of Forms has a theological flavour, and had a strong influence on the ideas of his Neo-Platonist interpreters Proclus and Plotinus.

[16] The pursuit of Truth, Beauty and Goodness became a central element in the apophatic tradition,[16] but nevertheless, according to Carabine "Plato himself cannot be regarded as the founder of the negative way.

[web 6] Middle Platonism proposed a hierarchy of being, with God as its first principle at its top, identifying it with Plato's Form of the Good.

[web 8] It is a product of Hellenistic syncretism, which developed due to the crossover between Greek thought and the Jewish scriptures, and also gave birth to Gnosticism.

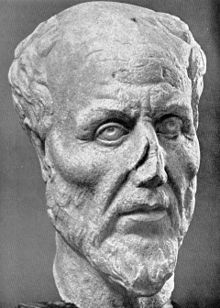

[web 7] Proclus of Athens (*412–485 AD) played a crucial role in the transmission of Platonic philosophy from antiquity to the Middle Ages., serving as head or 'successor' (diadochos, sc.

[25] In the Enneads Plotinus writes: Our thought cannot grasp the One as long as any other image remains active in the soul [...] To this end, you must set free your soul from all outward things and turn wholly within yourself, with no more leaning to what lies outside, and lay your mind bare of ideal forms, as before of the objects of sense, and forget even yourself, and so come within sight of that One.Carabine notes that Plotinus' apophasis is not just a mental exercise, an acknowledgement of the unknowability of the One, but a means to ecstasis and an ascent to "the unapproachable light that is God.

The term "silence" also alludes to the "still small voice" (1 Kings 19:12) whose revelation to Elijah on Mount Horeb rejected visionary imagery by affirming a negative theology.

[37][note 8]The Early Church Fathers were influenced by Philo[4] (c. 25 BC – 50 AD), who saw Moses as "the model of human virtue and Sinai as the archetype of man's ascent into the 'luminous darkness' of God.

[52]Saint Cyril of Jerusalem (313–386), in his Catechetical Homilies, states: For we explain not what God is but candidly confess that we have not exact knowledge concerning Him.

[53]Augustine of Hippo (354–430) defined God aliud, aliud valde, meaning 'other, completely other', in Confessions 7.10.16,[54] wrote Si [enim] comprehendis, non est Deus,[55] meaning 'if you understand [something], it is not God', in Sermo 117.3.5[56] (PL 38, 663),[57][58] and a famous legend tells that, while walking along the Mediterranean shoreline meditating on the mystery of the Trinity, he met a child who with a seashell (or a little pail) was trying to pour the whole sea into a small hole dug in the sand.

This remains transcendent to mankind's rational categories, a mystery which has to be guarded by apophatic language, as it is a personal union of a singularly unique kind.

[62] Apophatic theology found its most influential expression in the works of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (late 5th to early 6th century), a student of Proclus (412–485) who combined a Christian worldview with Neo-Platonic ideas.

[63] He is a constant factor in the contemplative tradition of the eastern Orthodox Churches, and from the 9th century onwards his writings also had a strong impact on western mysticism.

[64] Dionysius the Areopagite was a pseudonym, taken from Acts of the Apostles chapter 17, in which Paul gives a missionary speech to the court of the Areopagus in Athens.

[69] According to Corrigan and Harrington, "Dionysius' central concern is how a triune God [...] who is utterly unknowable, unrestricted being, beyond individual substances, beyond even goodness, can become manifest to, in, and through the whole of creation in order to bring back all things to the hidden darkness of their source.

[82][83][84]Thomas Aquinas was born ten years later (1225–1274) and, although in his Summa Theologiae he quotes Pseudo-Dionysius 1,760 times,[85] stating that "Now, because we cannot know what God is, but rather what He is not, we have no means for considering how God is, but rather how He is not"[86][87] and leaving the work unfinished because it was like "straw" compared to what had been revealed to him,[88] his reading in a neo-Aristotelian key[89] of the conciliar declaration overthrew its meaning inaugurating the "analogical way" as tertium between via negativa and via positiva: the via eminentiae.

[93][94] Apophatic statements are still crucial to many modern theologians, restarting in the 1800s by Søren Kierkegaard (see his concept of the infinite qualitative distinction)[95][96] up to Rudolf Otto, Karl Barth (see their idea of "Wholly Other", i.e. ganz Andere or totaliter aliter),[97][98][99] the Ludwig Wittgenstein of the Tractatus, and Martin Heidegger after his Kehre.

[108] Philosopher and literary scholar William Franke, particularly in his 2007 two-volume collection On What Cannot Be Said and his 2014 monograph A Philosophy of the Unsayable, puts forth that negative theology's exploration and performance of language's limitations is not simply one current among many in religious thought, but is "a kind of perennial counter-philosophy to the philosophy of Logos" that persistently challenges central tenets of Western thought throughout its history.

For Franke, literature demonstrates the "infinitely open" nature of language which negative theology and related forms of philosophical thought seek to draw attention to.

Franke therefore argues that literature, philosophy, and theology begin to bleed into one another as they approach what he frames as the "apophatic" side of Western thought.

They therefore hold that descriptors and qualifiers that occur in the Qur'ān and in the canonized religious traditions, even if seeming or sounding humanlike such as "hand", "finger, or "foot", are to be wholly affirmed as attributes of God (not limbs).

[121] Later in his career, such in as his essay "Sauf le nom", Derrida comes to see apophatic theology as potentially but not necessarily a means through which the intractable inadequacies of language and the ontological difficulties which proceed from them can brought to our attention and explored:[122] There is one apophasis that can in effect respond to, correspond to, correspond with the most insatiable desire of God, according to the history and the event of its manifestation or the secret of its non-manifestation.

[127]Buddhist philosophy has also strongly advocated the way of negation, beginning with the Buddha's own theory of anatta (not-atman, not-self) which denies any truly existent and unchanging essence of a person.

Madhyamaka is a Buddhist philosophical school founded by Nagarjuna (2nd–3rd century AD), which is based on a four-fold negation of all assertions and concepts and promotes the theory of emptiness (shunyata).

One problem noted with this approach is that there seems to be no fixed basis on deciding what God is not, unless the Divine is understood as an abstract experience of full aliveness unique to each individual consciousness, and universally, the perfect goodness applicable to the whole field of reality.