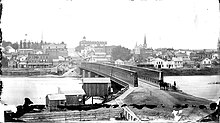

Dixon Bridge Disaster

A coroner's jury ruled that the Dixon City Council erred in judgment in selecting the Truesdell bridge design, which was determined to be faulty.

… He certainly has the best thing yet out … They are unequalled for strength and symmetry and are rapidly growing into favor.”[5] The Dixon city council took three ballots before finally favoring the Truesdell bid on a 5-3 vote.

Pratt later admitted to the Chicago Daily Tribune that he had detained the crowd longer than usual to impress upon them the advantage of ‘coming to Jesus.’ He added that he had no concerns of a bridge failure since he had conducted similar ceremonies at the same spot with “at least three times as many persons congregated on the same span to witness the immersion.”[13] By various accounts, the bridge had filled with at least 150 to 200 spectators, with the heaviest concentration on the sidewalk between the riverbank and the first pier.

The weak generally succumbed.” The 15 foot (4.6 m) truss “fell over with the weight, and imprisoned the doomed in an iron cage, with which they sunk, and from which there was no escape.” The hands and faces of some victims could be felt only six inches (150 mm) below the surface of the water, trapped under the debris.

[3] Several newspaper reports noted the ensuing panic in the water, as victims frantically grabbed at each other to get to the surface, while others fought off such grasps to avoid being pulled under.

[18] As the mass of bodies were thrown into the river, several citizens quickly brought ropes, planks, and boats to rescue the living and recover the dead.

Carpets and beds were given up freely, and services rendered that ought to give us a nobler estimate of humanity than has ever entered our conceptions.”[18] The extensive newspaper coverage of the event included many survivor stories.

Some poor fellow caught hold of me, and would have dragged me down, only I managed to get free and began striking out with my right hand.”[20] Other young men were noted for their stories of survival and rescue.

As the Chicago Inter-Ocean reported, “Stories of miraculous escapes and adventures are more rife than ever, and when facts fail, the power of invention is brought into play, each fiction-monger endeavoring to make his more readable than the last.”[2] With the large number of bodies in the water and the river current estimated at 8 miles per hour (13 km/h), the community had difficulty accounting for the saved, the lost, and the missing.

[22] On the next day, the Inter-Ocean added, “The scene of the wreck has been visited to-day by thousands of people who have come by train from … Chicago, Geneva, Sterling, Amboy, Mendota, and other places along the railway lines.”[17] Before the city established a free ferry to facilitate crossing, “rapacious sharks (were) reaping a rich harvest by charging outrageous rates.”[17] Business in town was suspended for several days, and schools were closed until further notice.

Church bells tolled continually, as the streets were occupied with dozens of funeral processions in the days after the disaster, including 13 on Tuesday alone.

They are Eliza Alexander, Irene Baker, Malinda Carpenter, Henrietta Cheney, Mary Cook, Minnie Florence Dana, Emily Deming, Edward Doyle, the daughter of Edward Doyle, Ida Drew, Robert Dyke, Julia Gilman, Christan Goble, Thomas Haley, Frederick Halpe, Francis (Frank) Hamilton, Lucia Hendrix, Althea Hendrix, Nettie Hill, Millie Hoffman, Elizabeth Hope, George Kent, Pamelia Kentner, Sarah Latta, Elizabeth (Lizzie) Mackey, Sarah March, Jay Mason, Henrietta Merriman, Agnes Nixon, Jane Ann Noble, Maggie O'Brien, P. (son of Mrs. John) O'Neal, Allie Petersberger, Fannie Petersberger, Bessie Rayne, Mary Sillman, Rosa Stackpole, Clara Stackpole, Katie Sterling, Eliza M. Vann, Ida Vann, Ann Wade, Elizabeth Wallace, Seth H. Whitmore, Mrs. W. Wilcox, and Melissa Wilhelm.

The Dixon Sun reported on May 7 that the story had found its way “around the globe.”[18] The news received prominent coverage throughout the nation in newspapers such as the New York Times, Washington (DC) Evening Star, Memphis Daily Appeal, Baltimore Sun, Detroit Free Press, New Orleans Times-Picayune, Philadelphia Inquirer, San Francisco Chronicle, and elsewhere.

As he was going down he was heard to exclaim, ‘___ ____ the Baptists.’ With the curse on his lips, he sank forever.”[3] On the following day, the Tribune’s story carried an editorial remark: “There are some people in this town—those in the habit of censuring Christians whenever they have an opportunity—who consider the Baptists, especially the Rev.

This is unfair …”[13] As several newspaper stories noted, the Baptists had conducted a number of public baptisms in the river previously, attracting large crowds, but with no incidents or injuries.

The press, still sensitive to misconduct by public officials from the Crédit Mobilier Scandal of 1872, quickly suspected that corruption was at the root of the Dixon debacle.

[18]On May 7, Chicago's Inter-Ocean newspaper reported that, in New York, a letter had been published that “distinctly and explicitly charged that Truesdell obtained the contract for building the bridge … by bribery.

It is said he bought four of the eight Aldermen of the city at prices ranging from $300 to $500 each.”[17] These bribery allegations swirled briefly in newspapers outside Dixon, but locally, the charges gained little traction.

When his input was not heeded, he would’ve resigned his position if he hadn’t been supported by City Attorney John V. Eustace and Alderman Porter.

[41] In an effort to collect other expert opinions about the Truesdell design, a Tribune reporter interviewed several prominent engineers in Chicago.

He explained, “(City officials) insisted on having their own way, and accused those who opposed them of advocating private interests and jobbery.”[3] Every Chicago engineer interviewed by the Tribune expressed “the unanimous verdict … that the State ought to cause the immediate destruction of every existing bridge of this pattern.” The Tribune report concluded that Truesdell “had the means to push his invention, and was thwarted only in the presence of men of science, who again and again declared it dangerous and useless.

The Tribune quoted J. K. Thompson, commissioner of the Chicago Board of Public Works, who said that Mr. Truesdell had succeeded in “foisting upon ignorant or unscrupulous authorities a miserable apology for a bridge.

He added, “The Dixon bridge could never have broken by any such weight as 200 or 250 persons, unless some important parts of the iron work had been fractured by the frosts of the past severe winter.

… If the city authorities had exercised due diligence in looking after its condition, the accident would never have happened, in all probability.”[8] The rumors that L. E. Truesdell was dead proved false when he emerged from silence from his home in Massachusetts, sending a letter to the Springfield (Mass.)

Can as much be said of any other plan?”[44] In the 1860s, Lucius E. Truesdell had built several bridges in Illinois, including in Chicago (Kinzie St. and Wells St.), Belvidere, Pecatonica, Elgin, and Geneva.

[48] The coroner's jury of May 7 gathered opinions from local citizens only, raising the possibility that their engineering analysis of the bridge was inadequate and incomplete.

The collapse of the Dixon bridge in 1873 attracted formal discussion at the ASCE's fifth annual convention, held in Louisville, Ky., on May 21–22, 1873, less than three weeks after the disaster.

[3] Several reports noted that the western sidewalk of the north side of the bridge, the area that proved to be a death trap, was filled with women and children.

Several newspaper stories noted that the county board included many farmers who disliked the heavy tolls they had to pay for using the Truesdell bridge.

The Sterling newspaper commented, “Correct theory, but not generous action in such a case.”[52] By June, the Dixon City Council was proceeding with building a temporary wooden bridge to enable continued transportation across the river.