Tsetse fly

They have pronounced economic and public health impacts in sub-Saharan Africa as the biological vectors of trypanosomes, causing human and animal trypanosomiasis.

The dipteran crop is heavily understudied, with Glossina being one of the few genera having relatively reliable information available: Moloo and Kutuza 1970 for G. brevipalpis (including its innervation) and Langley 1965 for G.

[8] The reproductive tract of adult females includes a uterus, which can become large enough to hold the third-instar larva at the end of each pregnancy.Most tsetse flies are, physically, very tough.

The newly-birthed larvae crawl into the ground and develop a hard outer shell (called the puparial case), within which they complete their morphological transformations into adult flies.

The importance of the richness and quality of blood to this stage can be seen; all tsetse development (prior to emerging from the puparial case as a full adult) occurs without feeding, with only the nutrition provided by the mother fly.

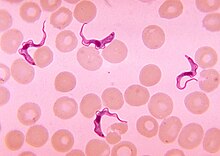

These trypanosomes, depending on the species, may remain in place, move to a different part of the digestive tract, or migrate through the tsetse body into the salivary glands.

[31] The trypanosomes are injected into vertebrate muscle tissue,[citation needed] but make their way, first into the lymphatic system, then into the bloodstream, and eventually into the brain.

The tsetse-vectored trypanosomiases affect various vertebrate species including humans, antelopes, bovine cattle, camels, horses, sheep, goats, and pigs.

A recent molecular study using restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis suggests that the three subspecies are polyphyletic,[36] so the elucidation of the strains of T. brucei infective to humans requires a more complex explanation.

The most notable is American trypanosomiasis, known as Chagas disease, which occurs in South America, caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, and transmitted by certain insects of the Reduviidae, members of the Hemiptera.

[38][39] The conquest of sleeping sickness and nagana would be of immense benefit to rural development and contribute to poverty alleviation and improved food security in sub-Saharan Africa.

Economic analysis indicates that the cost of managing trypanosomosis through the elimination of important populations of major tsetse vectors will be covered several times by the benefits of tsetse-free status.

[41] Area-wide interventions against the tsetse and trypanosomosis problem appear more efficient and profitable if sufficiently large areas, with high numbers of cattle, can be covered.

Tsetse fly eradication programmes are complex and logistically demanding activities and usually involve the integration of different control tactics, such as trypanocidal drugs, impregnated treated targets (ITT), insecticide-treated cattle (ITC), aerial spraying (Sequential Aerosol Technique - SAT) and in some situations the release of sterile males (sterile insect technique – SIT).

To ensure sustainability of the results, it is critical to apply the control tactics on an area-wide basis, i.e. targeting an entire tsetse population that is preferably genetically isolated.

[citation needed] Tsetse tend to rest on the trunks of trees so removing woody vegetation made the area inhospitable to the flies.

Some scientists put forward the idea that zebra have stripes, not as a camouflage in long grass, but because the black and white bands tend to confuse tsetse and prevent attack.

The sustainable removal of the tsetse fly is in many cases the most cost-effective way of dealing with the T&T problem resulting in major economic benefits for subsistence farmers in rural areas.

[51] The eradication of the tsetse fly from Unguja Island in 1997 was followed by the disappearance of the AAT which enabled farmers to integrate livestock keeping with cropping in areas where this had been impossible before.

[54] In the Niayes region of Senegal, a coastal area close to Dakar, livestock keeping was difficult due to the presence of a population of Glossina palpalis gambiensis.

After completion of the feasibility studies (2006–2010), an area-wide integrated eradication campaign that included an SIT component was started in 2011, and by 2015, the Niayes region had become almost tsetse fly free.

Results suggest that the tsetse decimated livestock populations, forcing early states to rely on slave labor to clear land for farming, and preventing farmers from taking advantage of natural animal fertilizers to increase crop production.

Qualitative support for this claim comes from archaeological findings; e.g., Great Zimbabwe is located in the African highlands where the fly does not occur, and represented the largest and technically most advanced precolonial structure in Southern sub-Sahara Africa.

[59] According to an article in the New Scientist, the depopulated and apparently primevally wild Africa seen in wildlife documentary films was formed in the 19th century by disease, a combination of rinderpest and the tsetse fly.

[61][additional citation(s) needed] The land was left emptied of its cattle and its people, enabling the colonial powers Germany and Britain to take over Tanzania and Kenya with little effort.

Highland regions of east Africa which had been free of tsetse fly were colonised by the pest, accompanied by sleeping sickness, until then unknown in the area.

[61][additional citation(s) needed] Although the colonial powers saw the disease as a threat to their interests, and acted accordingly to bring transmission almost to a halt in the 1960s,[62]: 0174 this improved situation led to a laxity of surveillance and management by the newly independent governments covering the same areas - and a resurgence that became a crisis again in the 1990s.

The disease nagana or African animal trypanosomiasis (AAT) causes gradual health decline in infected livestock, reduces milk and meat production, and increases abortion rates.

[10] The tsetse fly lives in nearly 10,000,000 square kilometres (4,000,000 sq mi) in sub-Saharan Africa[10] (mostly wet tropical forest) and many parts of this large area is fertile land that is left uncultivated—a so-called green desert not used by humans and cattle.

Eradicating the tsetse and trypanosomiasis (T&T) problem would allow rural Africans to use these areas for animal husbandry or the cultivation of crops and hence increase food production.