Cultural depictions of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, known variously as consumption, phthisis, and the great white plague, was long thought to be associated with poetic and artistic qualities in its sufferers, and was also known as "the romantic disease".

[2] Major artistic figures such as the poets John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Edgar Allan Poe; the composer Frédéric Chopin;[3] the playwrights Lesya Ukrainka[4] and Anton Chekhov; the novelists Franz Kafka, Katherine Mansfield,[5] the Brontë family, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Thomas Mann, W. Somerset Maugham,[6] and Robert Louis Stevenson;[7] and the artists Alice Neel,[8] Jean-Antoine Watteau, Elizabeth Siddal, Marie Bashkirtseff, Edvard Munch, Aubrey Beardsley and Amedeo Modigliani either had the disease or were surrounded by people who did.

Physical mechanisms proposed for this effect included the slight fever and the toxaemia caused by the disease, which allegedly helped them to see life more clearly and to act decisively.

This includes Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night, where the protagonist, Edmund, is diagnosed with tuberculosis at the start of the play; his mental anguish forms a substantial part of the drama.

Fyodor Dostoevsky used the theme of the consumptive nihilist repeatedly, with Katerina Ivanovna in Crime and Punishment, Kirillov in The Possessed, and both Ippolit and Marie in The Idiot.

[12] In French literature, Victor Hugo used the tuberculosis theme repeatedly: the disease is the likely cause of the spinal deformity of the hunchback in his 1831 novel Notre-Dame de Paris, while Fantine becomes ill and ultimately dies from consumption in his 1862 Les Misérables.

[9] The disease appears, too, in English novels of the Victorian era, including Charles Dickens's 1839 Nicholas Nickleby and his 1848 Dombey and Son, Elizabeth Gaskell's 1855 North and South, and Mrs. Humphry Ward's 1900 Eleanor.

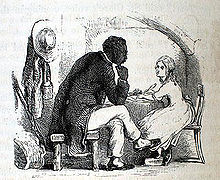

[13][14] In American literature, Little Eva dies a romanticised death of consumption over several chapters of Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Several novels by different authors have been set in Swiss sanatoriums for tuberculosis sufferers, including Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain,[15] A. E. Ellis's The Rack,[16] Liselotte Marshall's Tongue-Tied and Beatrice Harraden's Ships That Pass in the Night.

For example, John le Carré's 2001 The Constant Gardener, and its film adaptation, tells the tale of the testing of anti-tuberculosis drugs on unwitting subjects in Africa.

For example, in A. J. Cronin's best-known novel, The Citadel (1937), made into a 1938 film of the same name by King Vidor, the idealistic protagonist, Dr. Andrew Manson, is dedicated to treating Welsh miners suffering from tuberculosis.

[23] Shame is brought to Sheilagh Fielding's Newfoundland family in Wayne Johnston's The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, as she has tuberculosis even though her father is a doctor.

[27] Drunken Angel, a 1948 film by Akira Kurosawa, is the story of a doctor (Takashi Shimura) who is obsessed with curing tuberculosis in his patients, including a young yakuza (Toshirō Mifune) whose illness is being used by his organization as a biological weapon.

[30] In the 1994 film Heavenly Creatures, directed by Peter Jackson and based on a true story, Juliet Hulme (Kate Winslet) had the disease, and her fear of being sent away 'for the good of her health' played a large role in determining subsequent actions.

[8] The permanent collection of the American Visionary Art Museum contains a life-size applewood sculpture, Recovery, of a tuberculosis sufferer with a sunken chest.

Faced with his own mortality, he becomes more conscious of his actions and tries to better himself in the time he has left, doing his best to give the remaining members of the Van der Linde gang an opportunity at a better life following his death, all the while seeking redemption for his past behaviour.