Hammam

[2][3][4] Muslim bathhouses or hammams were historically found across the Middle East, North Africa, al-Andalus (Islamic Iberia, i.e. Spain and Portugal), Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and in Southeastern Europe under Ottoman rule.

This stems from the tendency of historical Western writers to conflate ethnic and religious terms by referring to Muslims as "Turk" and because they presented hammams largely as an Ottoman cultural feature.

[13][14][15]Following the expansion of Arab Muslim rule over much of the Middle East and North Africa in the 7th and 8th centuries, the emerging Islamic societies were quick to adapt the bathhouse to their own needs.

[16] He suggests that the hammam's initial appeal derived at least in part from its convenience for other services (such as shaving), from its endorsement by some Muslim doctors as a form of therapy, and from the continued popular appreciation of its pleasures in a region where they had already existed for centuries.

[16][17] These scholars viewed hammams as unnecessary for full-body ablutions (ghusl) and questioned whether public bathing spaces could be sufficiently clean to achieve proper purification.

[17] In Iran, which did not previously have a strong culture of public bathing, historical texts mention the existence of bathhouses in the 10th century as well as the use of hot springs for therapeutic purposes; however, there has been relatively little archeological investigation to document the early presence and development of hammams in this region.

During those centuries of war, peace, alliance, trade and competition, these intermixing cultures (Eastern Roman, Islamic Persian and Turkic) had tremendous influence on each other.

[22] When Sultan Mustafa III issued a decree halting the construction of new public baths in the city in 1768, it seems to have resulted in an increase in the number of private hammams among the wealthy and the elites, especially in the Bosphorus suburbs where they built luxurious summer homes.

[27] Hammams continued to be a vital part of urban life in the Muslim world until the early 20th century when the spread of indoor plumbing in private homes rendered public baths unnecessary for personal hygiene.

[32] In the former European territories of the Ottoman Empire such as Greece and the Balkans, many hammams became defunct or were neglected in modern times, although some have now been restored and turned into historic monuments or cultural centres.

[36] His writing focused especially on the need to avoid touching the penis during bathing and after urination, and wrote that nakedness was decent only when the area between a man's knees and lower stomach was hidden.

[citation needed] Some accessories from Roman times survive in modern hammams, such as the peştemal (a special cloth of silk and/or cotton to cover the body, like a pareo) and the kese (a rough mitten used for scrubbing).

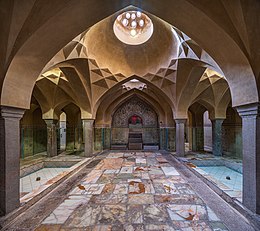

Fictional Arab people South Arabian deities The hammam combines the functionality and structural elements of the Roman thermae with the Islamic tradition of steam bathing, ritual cleansing and respect for water.

The changing room was known generally as al-mashlaḥ or al-maslakh in Arabic, or by local vernacular terms like goulsa in Fez (Morocco) and maḥras in Tunisia, whereas it was known as the camekân in Turkish and the sarbineh in Persian.

The hot room was called the bayt al-sakhun in al-Andalus, ad-dakhli in Fez, harara in Cairo, garmkhaneh in Persian, and hararet or sıcaklık in Turkish.

[2][4][5] Qusayr 'Amra is particularly notable for the frescoes in late Roman style that decorate the chambers, presenting a highly important example of Islamic art in its early historical stages.

[57][55][17] In 2020 a well-preserved 12th-century Almohad-period bathhouse, complete with painted geometric decoration, was discovered during renovations of a local tapas bar in Seville, near the Giralda tower.

[62] The oldest known Islamic baths in Algeria are those uncovered by archeologists, including one in Tahert from the Rustamid period (8th–9th centuries), one near the mosque of Agadir (part of present-day Tlemcen), and one at the 10th-century Zirid palace of 'Ashir.

The Great Bath located in present-day Pakistan is a notable example dating from the 3rd millennium BC at the archeological site of Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley.

This was due to the fact that, unlike most cities in those regions, water was readily available across much of India, making hammams less essential for bathing and performing full ablutions.

[24] Most have been abandoned, demolished or survive in a state of decay, but recently a growing number have been restored and converted to serve new cultural functions as historic sites or exhibitions spaces.

[citation needed] Elsewhere in Greece, the Abid Efendi Hamam, built between 1430 and 1669 near the Roman Forum in Athens, restored in the 1990s and converted to the Center of Documentation in Body Embellishment.

The unknown author wrote that he had wanted "to erect baths at the expense of government in different parts of London, after the manner of the Roman thermæ, publicly endowed like hospitals for the use of the people," and that in 1818 he had unsuccessfully tried to interest George III in his project.

Covering an area of 7,500 square metres, it also includes a madrasa (school), library, conference hall and, beyond the Moorish gardens, an annexe housing a hammam and a tearoom with a direct entrance to the street.

Constructed in reinforced concrete, the decorative green tiles, earthenware, mosaics, and wrought iron work come from Maghreb countries, and were fitted by craft workers from there.

[137] Drawing on centuries of mixed traditions, their signs in Spanish and English, they are promoting a new view of the hammam to a younger generation of bathers, thereby attracting both tourists and locals, a trend currently developing around the continent.

[138] A famous painting by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Le Bain Turc ("The Turkish Bath"), depicts these spaces as magical and sexual.

Turkish director Ferzan Özpetek's 1997 film Hamam told the story of a man who inherited a hammam in Istanbul from his aunt, restored it and found a new life for himself in the process.

One such was the British diplomat's wife, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who visited a hammam in Sofia in Bulgaria in 1717 and wrote about it in her Turkish Embassy Letters, first published in 1763.

[141] In 1836 another British woman, the traveller and novelist, Julia Pardoe, left a description of taking part in the hammam ritual in Constantinople/Istanbul in her book The City of the Sultan and Domestic Manners of the Turks, published in 1838.