Tuskegee Syphilis Study

[12] The study continued, under numerous Public Health Service supervisors, until 1972, when a leak to the press resulted in its termination on November 16 of that year.

[15] In 1997, President Bill Clinton formally apologized on behalf of the United States to victims of the study, calling it shameful and racist.

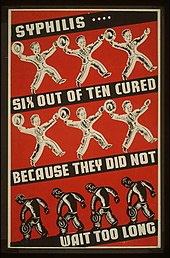

[2] Initially, subjects were studied for six to eight months and then treated with contemporary methods, including Salvarsan ("606"), mercurial ointments, and bismuth, which were mildly effective and highly toxic.

[20] The researchers reasoned that the knowledge gained would benefit humankind; however, it was determined afterward that the doctors did harm their subjects by depriving them of appropriate treatment once it had been discovered.

"[21] To ensure that the men would show up for the possibly dangerous, painful, diagnostic, and non-therapeutic spinal taps, doctors sent participants a misleading letter titled "Last Chance for Special Free Treatment".

[26] The venereal disease section of the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) formed a study group in 1932 at its national headquarters in Washington, D.C. Taliaferro Clark, head of the USPHS, is credited with founding it.

[31] Raymond A. Vonderlehr was appointed on-site director of the research program and developed the policies that shaped the long-term follow-up section of the project.

His method of gaining the "consent" of the subjects for spinal taps (to look for signs of neurosyphilis) was by advertising this diagnostic test as a "special free treatment".

[2] Several African-American health workers and educators associated with the Tuskegee Institute played a critical role in the study's progress.

[32] Nurse Eunice Rivers, who had trained at Tuskegee Institute and worked at its hospital, was recruited at the start of the study to be the main point of contact with the participants.

[4] Several men employed by the PHS, namely Austin V. Deibert and Albert P. Iskrant, expressed criticism of the study, primarily on the grounds of poor scientific practice.

[4] In 1966, Peter Buxtun, a PHS venereal-disease investigator in San Francisco, sent a letter to the national director of the Division of Venereal Diseases expressing his concerns about the ethics and morality of the extended U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee.

Following that, interested parties formed the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee to develop ideas that had arisen at the symposium, chaired by Vanessa Northington Gamble.

[38] The Committee had two related goals:[38] A year later on May 16, 1997, Bill Clinton formally apologized and held a ceremony at the White House for surviving Tuskegee study participants.

[41] In 2009, the Legacy Museum opened in the Bioethics Center, to honor the hundreds of participants of the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the African American Male.

[43] The five survivors who attended the White House ceremony in 1997 were Charlie Pollard, Herman Shaw, Carter Howard, Fred Simmons, and Frederick Moss.

Charlie Pollard appealed to civil rights attorney Fred D. Gray, who also attended the White House ceremony, for help when he learned the true nature of the study he had been participating in for years.

[4] Another participant of the study was Freddie Lee Tyson, a sharecropper who helped build Moton Field, where the legendary "Tuskegee Airmen" learned to fly during World War II.

Because participants were treated with mercury rubs, injections of neoarsphenamine, protiodide, Salvarsan, and bismuth, the study did not follow subjects whose syphilis was untreated, however minimally effective these treatments may have been.

[2][4] Austin V. Deibert of the PHS recognized that since the study's main goal had been compromised in this way, the results would be meaningless and impossible to manipulate statistically.

[2][44] Taliaferro Clark said, "The rather low intelligence of the Negro population, depressed economic conditions, and the common promiscuous sex relations not only contribute to the spread of syphilis but the prevailing indifference with regards to treatment.

"[44] In reality, the promise of medical treatment, usually reserved only for emergencies among the rural black population of Macon County, Alabama, was what secured subjects' cooperation in the study.

She called attention to a broader historical and social context that had already negatively influenced community attitudes, including countless prior medical injustices before the study's start in 1932.

These dated back to the antebellum period, when slaves had been used for unethical and harmful experiments including tests of endurance against and remedies for heatstroke and experimental gynecological surgeries without anesthesia.

[48] A 2016 paper by Marcella Alsan and Marianne Wanamaker found "that the historical disclosure of the [Tuskegee experiment] in 1972 is correlated with increases in medical mistrust and mortality and decreases in both outpatient and inpatient physician interactions for older black men.

[54] In February 1992 on ABC's Prime Time Live, journalist Jay Schadler interviewed Dr. Sidney Olansky, Public Health Services director of the study from 1950 to 1957.

[55] In 2001, a court compared the Kennedy Krieger Institute's Lead-Based Paint Abatement and Repair and Maintenance Study to the Tuskegee experiments.

[57] In September 2021, the right-wing group America's Frontline Doctors, which has promoted COVID-19 conspiracy theories and misinformation, filed a lawsuit against New York City, claiming that its vaccine passport health orders were inherently discriminatory against African Americans due to the "historical context".

[16] In the period following World War II, the revelation of the Holocaust and related Nazi medical abuses brought about changes in international law.

Lloyd Clements, Jr. has worked with noted historian Susan Reverby concerning his family's involvement with the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee.