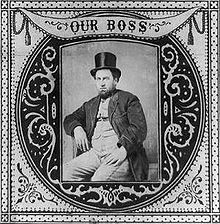

William M. Tweed

[3] Tweed was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1852 and the New York County Board of Supervisors in 1858, the year that he became the head of the Tammany Hall political machine.

However, Tweed's greatest influence came from being an appointed member of a number of boards and commissions, his control over political patronage in New York City through Tammany, and his ability to ensure the loyalty of voters through jobs he could create and dispense on city-related projects.

[5] At the time, volunteer fire companies competed vigorously with each other; some were connected with street gangs and had strong ethnic ties to various immigrant communities.

However, fire companies were also recruiting grounds for political parties at the time, thus Tweed's exploits came to the attention of the Democratic politicians who ran the Seventh Ward.

Several months later, in April, he became "Grand Sachem", and began to be referred to as "Boss", especially after he tightened his hold on power by creating a small executive committee to run the club.

[19][20] The new charter put control of the city's finances in the hands of a Board of Audit, which consisted of Tweed, who was Commissioner of Public Works, Mayor A. Oakey Hall and Comptroller Richard "Slippery Dick" Connolly, both Tammany men.

[23] Contractors working for the city – "Ring favorites, most of them – were told to multiply the amount of each bill by five, or ten, or a hundred, after which, with Mayor Hall's 'O.

[26]: 3 [27] After the Tweed Charter to reorganize the city's government was passed in 1870, four commissioners for the construction of the New York County Courthouse were appointed.

They would buy up undeveloped property, then use the resources of the city to improve the area – for instance by installing pipes to bring in water from the Croton Aqueduct – thus increasing the value of the land, after which they sold and took their profits.

Despite the corruption of Tweed and Tammany Hall, they did accomplish the development of upper Manhattan, though at the cost of tripling the city's bond debt to almost $90 million.

In order to ensure that the Brooklyn Bridge project would go forward, State Senator Henry Cruse Murphy approached Tweed to find out whether New York's aldermen would approve the proposal.

Tweed's response was that $60,000 for the aldermen would close the deal, and contractor William C. Kingsley put up the cash, which was delivered in a carpet bag.

James Watson, who was a county auditor in Comptroller Dick Connolly's office and who also held and recorded the ring's books, died a week after his head was smashed by a horse in a sleigh accident on January 24, 1871.

The riot was prompted after Tammany Hall banned a parade of Irish Protestants celebrating a historical victory against Catholicism, namely the Battle of the Boyne.

They were able to force an examination of the city's books, but the blue-ribbon commission of six businessmen appointed by Mayor A. Oakey Hall, a Tammany man, which included John Jacob Astor III, banker Moses Taylor and others who benefited from Tammany's actions, found that the books had been "faithfully kept", letting the air out of the effort to dethrone Tweed.

[35] More important, the Times started to receive inside information from County Sheriff James O'Brien, whose support for Tweed had fluctuated during Tammany's reign.

O'Brien had tried to blackmail Tammany by threatening to expose the ring's embezzlement to the press, and when this failed he provided the evidence he had collected to the Times.

[36] Shortly afterward, county auditor Matthew J. O'Rourke supplied additional details to the Times,[36] which was reportedly offered $5 million to not publish the evidence.

Property owners refused to pay their municipal taxes, and a judge—Tweed's old friend George Barnard—enjoined the city Comptroller from issuing bonds or spending money.

Green loosened the purse strings again, allowing city departments not under Tammany control to borrow money to operate.

[41] After his release from The Tombs prison, New York State filed a civil suit against Tweed, attempting to recover $6 million in embezzled funds.

The Tweed ring at its height was an engineering marvel, strong and solid, strategically deployed to control key power points: the courts, the legislature, the treasury and the ballot box.

The theme is that the sins of corruption so violated American standards of political rectitude that they far overshadow Tweed's positive contributions to New York City.

Seymour J. Mandelbaum has argued that, apart from the corruption he engaged in, Tweed was a modernizer who prefigured certain elements of the Progressive Era in terms of more efficient city management.

Much of the money he siphoned off from the city treasury went to needy constituents who appreciated the free food at Christmas time and remembered it at the next election, and to precinct workers who provided the muscle of his machine.

He facilitated the founding of the New York Public Library, even though one of its founders, Samuel Tilden, was Tweed's sworn enemy in the Democratic Party.

[49][50] Tweed recognized that the support of his constituency was necessary for him to remain in power, and as a consequence he used the machinery of the city's government to provide numerous social services, including building more orphanages, almshouses and public baths.

[5][51] Tweed also fought for the New York State Legislature to donate to private charities of all religious denominations, and subsidize Catholic schools and hospitals.

Hershkowitz blames the implications of Thomas Nast in Harper's Weekly and the editors of The New York Times, which both had ties to the Republican party.

I claim to be a live man, and hope (Divine Providence permitting) to survive in all my vigor, politically and physically, some years to come.