Typhoid fever

enterica serovar Typhi growing in the intestines, Peyer's patches, mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, liver, gallbladder, bone marrow and blood.

[5][2][11] Recently, new advances in large-scale data collection and analysis have allowed researchers to develop better diagnostics, such as detecting changing abundances of small molecules in the blood that may specifically indicate typhoid fever.

[12] Diagnostic tools in regions where typhoid is most prevalent are quite limited in their accuracy and specificity, and the time required for a proper diagnosis, the increasing spread of antibiotic resistance, and the cost of testing are also hardships for under-resourced healthcare systems.

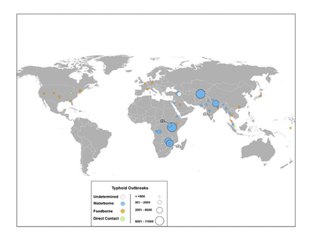

[25] Global phylogeographical analysis showed dominance of a haplotype 58 (H58), which probably originated in India during the late 1980s and is now spreading through the world with multi-drug resistance.

[28] Diagnosis is made by any blood, bone marrow, or stool cultures and with the Widal test (demonstration of antibodies against Salmonella antigens O-somatic and H-flagellar).

In epidemics and less wealthy countries, after excluding malaria, dysentery, or pneumonia, a therapeutic trial time with chloramphenicol is generally undertaken while awaiting the results of the Widal test and blood and stool cultures.

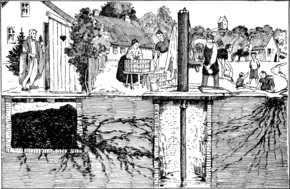

[36] According to statistics from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the chlorination of drinking water has led to dramatic decreases in the transmission of typhoid fever.

[38] To help decrease rates of typhoid fever in developing nations, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the use of a vaccination program starting in 1999.

One study found a 30-day mortality rate of 9% (8/88), and surgical site infections at 67% (59/88), with the disease burden borne predominantly by low-resource countries.

Many centres are shifting from ciprofloxacin to ceftriaxone as the first line for treating suspected typhoid originating in South America, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Thailand, or Vietnam.

enterica serovar Typhi is human-restricted, these chronic carriers become the crucial reservoir, which can persist for decades for further spread of the disease, further complicating its identification and treatment.

[91] The French doctors Pierre-Fidele Bretonneau and Pierre-Charles-Alexandre Louis are credited with describing typhoid fever as a specific disease, unique from typhus.

Both doctors performed autopsies on individuals who died in Paris due to fever – and indicated that many had lesions on the Peyer's patches which correlated with distinct symptoms before death.

[82] Pierre-Charlles-Alexandre Louis also performed case studies and statistical analysis to demonstrate that typhoid was contagious – and that persons who already had the disease seemed to be protected.

[82] Afterward, several American doctors confirmed these findings, and then Sir William Jenner convinced any remaining skeptics that typhoid is a specific disease recognizable by lesions in the Peyer's patches by examining sixty-six autopsies from fever patients and concluding that the symptoms of headaches, diarrhea, rash spots, and abdominal pain were present only in patients who were found to have intestinal lesions after death; these observations solidified the association of the disease with the intestinal tract and gave the first clue to the route of transmission.

[82] In 1847 William Budd learned of an epidemic of typhoid fever in Clifton, and identified that all 13 of 34 residents who had contracted the disease drew their drinking water from the same well.

[82] Notably, this observation was two years before John Snow first published an early version of his theory that contaminated water was the central conduit for transmitting cholera.

Budd later became health officer of Bristol ensured a clean water supply, and documented further evidence of typhoid as a water-borne illness throughout his career.

[82] In April 1880, three months before Eberth's publication, Edwin Klebs described short and filamentous bacilli in the Peyer's patches in typhoid victims.

[98] Most developed countries had declining rates of typhoid fever throughout the first half of the 20th century due to vaccinations and advances in public sanitation and hygiene.

[104][87] Although other cases of human-to-human spread of typhoid were known at the time, the concept of an asymptomatic carrier, who was able to transmit disease, had only been hypothesized and not yet identified or proven.

[82] At the time of Mallon's tenure as a personal cook for upper-class families, New York City reported 3,000 to 4,500 cases of typhoid fever annually.

[106] All cases were concluded to be due to a single milk farm worker, who was shedding large amounts of the typhoid pathogen in his urine.

[106] Pharmaceutical treatment decreased the amount of bacteria secreted, however, the infection was never fully cleared from the urine, and the carrier was released "under orders never again to engage in the handling of foods for human consumption.

"[106] At the time of release, the authors noted "for more than fifty years he has earned his living chiefly by milking cows and knows little of other forms of labor, it must be expected that the closest surveillance will be necessary to make certain that he does not again engage in this occupation.

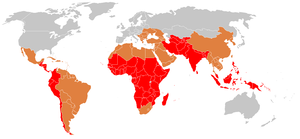

[107] Today, typhoid carriers exist all over the world, but the highest incidence of asymptomatic infection is likely to occur in South/Southeast Asian and Sub-Saharan countries.

[109] Fecal or gallbladder carrier release requirements: 6 consecutive negative feces and urine specimens submitted at 1-month or greater intervals beginning at least 7 days after completion of therapy.

[109] Urinary or kidney carrier release requirements: 6 consecutive negative urine specimens submitted at 1-month or greater intervals beginning at least 7 days after completion of therapy.

[111] British bacteriologist Almroth Edward Wright first developed an effective typhoid vaccine at the Army Medical School in Netley, Hampshire.

Wright further developed his vaccine at a newly opened research department at St Mary's Hospital Medical School in London in 1902, where he established a method for measuring protective substances (opsonin) in human blood.