Tyrannosauroidea

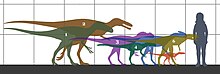

Tyrannosauroidea (meaning 'tyrant lizard forms') is a superfamily (or clade) of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs that includes the family Tyrannosauridae as well as more basal relatives.

By the end of the Cretaceous Period, tyrannosauroids were the dominant large predators in the Northern Hemisphere, culminating in the gigantic Tyrannosaurus.

[5] Teeth from Lower Cretaceous rocks (140 to 136 million years old) of Hyogo, Japan, appear to have come from an approximately 5 metres (16 ft) long animal, possibly indicating an early size increase in the lineage.

[10] Derived tyrannosaurids have forelimbs strongly reduced in size, the most extreme example being Tarbosaurus from Mongolia, where the humerus was only one-quarter the length of the femur.

Characteristic features of the tyrannosauroid pelvis include a concave notch at the upper front end of the ilium, a sharply defined vertical ridge on the outside surface of the ilium, extending upwards from the acetabulum (hip socket), and a huge "boot" on the end of the pubis, more than half as long as the shaft of the pubis itself.

Tyrannosauroid hindlimbs are longer relative to body size than almost any other theropods, and show proportions characteristic of fast-running animals, including elongated tibiae and metatarsals.

[15] This structure was shared by derived ornithomimids, troodontids and caenagnathids,[16] but was not present in basal tyrannosauroids like Dilong paradoxus, indicating convergent evolution.

The first was by Paul Sereno in 1998, where Tyrannosauroidea was defined as a stem-based taxon including all species sharing a more recent common ancestor with Tyrannosaurus rex than with neornithean birds.

[21] To make the family more exclusive, Thomas Holtz redefined it in 2004 to include all species more closely related to Tyrannosaurus rex than to Ornithomimus velox, Deinonychus antirrhopus or Allosaurus fragilis.

[3][36][38] While many place tyrannosauroids as basal coelurosaurs, Paul Sereno in his 1990s analysis of theropods would find the Tyrannosaurs to be sister taxa to the Maniraptora with them being closer to birds than Ornithomimosaurs were.

[39] A 2007 analysis found the family Coeluridae, including the Late Jurassic North American genera Coelurus and Tanycolagreus, to be the sister group of Tyrannosauroidea.

[4][5] Dryptosaurus, long a difficult genus to classify, has turned up in several recent analyses as a basal tyrannosauroid as well, slightly more distantly related to Tyrannosauridae than Eotyrannus and Appalachiosaurus.

[12][43] Below on the left is a cladogram of Tyrannosauroidea from a 2022 study by Darren Naish and Andrea Cau on the genus Eotyrannus, and on the right is a cladogram of Eutyrannosauria from a 2020 study by Jared T. Voris and colleagues on the genus Thanatotheristes:[44][45] Juratyrant Stokesosaurus Dilong Guanlong Proceratosaurus Sinotyrannus Yutyrannus Xiongguanlong Aniksosaurus Fukuiraptor Australovenator Orkoraptor Dryptosaurus Bistahieversor Tyrannosauridae Dryptosaurus aquilunguis Appalachiosaurus montgomeriensis Bistahieversor sealeyi Gorgosaurus libratus Albertosaurus sarcophagus Qianzhousaurus sinensis Alioramus remotus Alioramus altai Teratophoneus curriei Dynamoterror dynastes Lythronax argestes Nanuqsaurus hoglundi Thanatotheristes degrootorum Daspletosaurus torosus Daspletosaurus horneri Zhuchengtyrannus magnus Tarbosaurus bataar Tyrannosaurus rex In 2018 authors Rafael Delcourt and Orlando Nelson Grillo published a phylogenetic analysis of Tyrannosauroidea which incorporated taxa from the ancient continent of Gondwana (which today consists of the southern hemisphere), such as Santanaraptor and Timimus, whose placement in the group has been controversial.

The first is Pantyrannosauria referring to all non-proceratosaurid members of the group, while Eutyrannosauria for larger tyrannosaur taxa found in the northern hemisphere such as Dryptosaurus, Appalachiosaurus, Bistahieversor, and Tyrannosauridae.

[46] Guanlong wucaii Proceratosaurus bradleyi Kileskus aristotocus Sinotyrannus kazuoensis Yutyrannus huali Aviatyrannis jurassica Dilong paradoxus Santanaraptor placidus Timimus hermani Stokesosaurus clevelandi Juratyrant langhami Eotyrannus lengi Xiongguanlong baimoensis NMV P186046 ("Australian tyrannosaur") Alectrosaurus olseni Timurlengia euotica Dryptosaurus aquilunguis Appalachiosaurus montgomeriensis Bistahieversor sealeyi Gorgosaurus libratus Albertosaurus sarcophagus Qianzhousaurus sinensis Alioramus remotus Alioramus altai Nanuqsaurus hoglundi Teratophoneus curriei Lythronax argestes Daspletosaurus torosus Daspletosaurus horneri Zhuchengtyrannus magnus Tarbosaurus bataar Tyrannosaurus rex In 2021, Chase Brownstein published a research article based on more thorough descriptions of tyrannosauroid metatarsals and vertebra from the Merchantville Formation in Delaware.

[47] This reanalysis of phylogenetic relationships of tyrannosauroids in Appalachia has brought the rediscovery of the clade Dryptosauridae due to the similarities of metatarsals II and IV with the same bones in the Dryptosaurus holotype.

The earliest recognized tyrannosauroids lived in the Middle Jurassic, represented by the proceratosaurids Kileskus from the Western Siberia and Proceratosaurus from Great Britain.

Upper Jurassic tyrannosauroids include Guanlong from China, Stokesosaurus from the western United States and Aviatyrannis and Juratyrant from Europe.

Early Cretaceous tyrannosauroids are known from Laurasia, being represented by Eotyrannus from England[7] and Dilong, Sinotyrannus, and Yutyrannus from northeastern China.

The absence of tyrannosaurids from the eastern part of the continent suggests that the family evolved after the appearance of the seaway, allowing basal tyrannosauroids like Dryptosaurus and Appalachiosaurus to survive in the east as a relict population until the end of the Cretaceous.

NMV P186069, a partial pubis (a hip bone) with a supposed distinctive tyrannosauroid-like form, was discovered in Dinosaur Cove in Victoria.

[66] These filaments have usually been interpreted as "protofeathers," homologous with the branched feathers found in birds and some non-avian theropods,[67][68] although other hypotheses have been proposed.

[4] A scientific publication by Phil Bell and colleagues in 2017 show that tyrannosaurids such as Gorgosaurus, Tarbosaurus, Albertosaurus, Daspletosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus had scales.

The Bell et al. 2017 paper notes that the scale-like integument on bird feet were actually secondarily derived feathers according to paleontological and evolutionary developmental evidence so they hypothesize that the scaly skin preserved on some tyrannosaurid specimens might be secondarily derived from filamentous appendages like on Yutyrannus although strong evidence is needed to support this hypothesis.

The most elaborate is found in Guanlong, where the nasal bones support a single, large crest which runs along the midline of the skull from front to back.

[5] A less prominent crest is found in Dilong, where low, parallel ridges run along each side of the skull, supported by the nasal and lacrimal bones.

Similarly to the unwieldy tail of a male peacock or the outsized antlers of an Irish elk, the crest of Guanlong may have evolved via sexual selection, providing an advantage in courtship that outweighed any decrease in hunting ability.