USS Scorpion (SSN-589)

SUBSAFE required intensive vetting of submarine component quality, coupled with various improvements and intensified structural inspections – particularly of hull welding, using ultrasonic testing.

[citation needed] Chief of Naval Operations Admiral David Lamar McDonald approved Scorpion's reduced overhaul on 17 June 1966.

[verification needed] In late October 1967, Scorpion started refresher training and weapons-system acceptance tests, and was given a new commanding officer, Francis Slattery.

No evidence was found that Scorpion's speed was restricted in May 1968, although it was conservatively observing a depth limitation of 500 feet (150 m), due to the incomplete implementation of planned post-Thresher safety checks and modifications.

[9] After departing the Mediterranean on 16 May, Scorpion dropped two men at Naval Station Rota in Spain, one for a family emergency and one for health reasons.

The search continued with a team of mathematical consultants led by John Piña Craven, the chief scientist of the Navy's Special Projects Division.

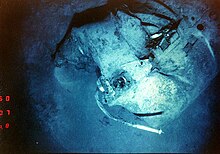

[15] At the end of October 1968, the Navy's oceanographic research ship Mizar located sections of the hull of Scorpion on the seabed, about 400 nmi (740 km) southwest of the Azores[16] under more than 9,800 ft (3,000 m) of water.

[17] The court of inquiry was subsequently reconvened, and other vessels, including the bathyscaphe Trieste II, were dispatched to the scene to collect pictures and other data.

Craven received much credit for locating the wreckage of Scorpion, although Gordon Hamilton was instrumental in defining a compact "search box" wherein the wreck was ultimately found.

He was an acoustics expert who pioneered the use of hydroacoustics to pinpoint Polaris missile splashdown locations, and he had established a listening station in the Canary Islands, which obtained a clear signal of the vessel's pressure hull imploding as it passed crush depth.

Naval Research Laboratory scientist Chester Buchanan used a towed camera sled of his own design aboard Mizar and finally located Scorpion.

"[18] In 1984, the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot and The Ledger-Star obtained documents related to the inquiry, and reported that the likely cause of the disaster was the detonation of a torpedo while the Scorpion's own crew attempted to disarm it.

[20] An extensive, year-long analysis of Gordon Hamilton's hydroacoustic signals of the submarine's demise was conducted by Robert Price, Ermine Christian, and Peter Sherman of the Naval Ordnance Laboratory (NOL).

This appears to differ from conclusions drawn by Craven and Hamilton, who pursued an independent set of experiments as part of the same phase II probe, demonstrating that alternate interpretations of the hydroacoustic signals were possibly based on the submarine's depth at the time it was stricken and other operational conditions.

[citation needed] The Structural Analysis Group (SAG) concluded that an explosive event was unlikely and was highly dismissive of Craven and Hamilton's tests.

Nonetheless, Sterlet was a small World War II-era diesel-electric submarine of a vastly different design and construction from Scorpion with regard to its pressure hull and other characteristics.

[24][25] Due to the radioactive nature of the Scorpion wreck site, the U.S. Navy has had to publish what specific environmental sampling it has done of the sediment, water, and marine life around the sunken submarine to establish what impact it has had on the deep-ocean environment.

A private group including family members of the lost submariners stated they would investigate the wreckage on their own, since it was located in international waters.

[27] Retired acoustics expert Bruce Rule, a long-time analyst for the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS), wrote that a hydrogen explosion sank Scorpion.

The acoustic homing torpedo, in a fully ready condition and lacking a propeller guard, is theorized by some to have started running within the tube.

The book Blind Man's Bluff documents findings and investigation by John Craven, who was the chief scientist of the Navy's Special Projects Office, which had management responsibility for the design, development, construction, operational test and evaluation, and maintenance of the UGM-27 Polaris fleet missile system.

[37] The book All Hands Down by Kenneth Sewell and Jerome Preisler (Simon and Schuster, 2008) concludes that Scorpion was destroyed while en route to gather intelligence on a Soviet naval group conducting operations in the Atlantic.

"[46] All Hands Down[9] was written by Kenneth R. Sewell, a nuclear engineer and a U.S. Navy veteran who spent five years aboard Parche, a fast attack submarine.

It attempts to link the sinking of Scorpion with the Pueblo incident, the John Anthony Walker spy ring, and Cold War Soviet aggression.

The bait for this trap would be strange military operations and furtive naval manoeuvres in the Atlantic, accompanied by countermeasures that would seemingly be defeated only by the deployment of a nuclear submarine.

[citation needed] The book then purports a cover-up by American and Soviet officials, to avoid public outrage and an increase in Cold War tension.

[citation needed] Ed Offley, a reporter on military affairs, has closely followed developments in information concerning the sinking of the Scorpion.

These machines, combined with daily crypto keys from the Walker spy ring, likely allowed the Soviets to monitor U.S. Navy ship dispositions and communications.

He claims the U.S. Navy was aware of the loss of the Scorpion on 21 May 1968, and by the night of 22 May 68, deep concern had arisen over the Scorpion after not receiving the required 24-hr, four-word communication check required on operational duty, in the SUBCOMLANT communication center at Norfolk on the evidence of two 2nd-class radiomen on the deck that night, among junior USN officers, and the unit supervisor, Warrant Officer J. Walker, confirmed to interested staff that no check transmission from Scorpion was received that night, and by the morning of 23 May 1968, the SUBCOMLANT center was full of admirals and a Marine general, and no doubt interested about the loss of Scorpion,[47] and the US government and Navy were engaged in a massive cover-up, within days destroying much of the sound and communication data at SOSUS ground stations in the U.S. and Europe,[48] and delaying any public indication of the loss until the ship's scheduled arrival at Norfolk, Virginia, five days later, partly to disguise the fact that U.S. nuclear subs were in constant or frequent communication with U.S. naval communication bases and that the subsequent search for the Scorpion was a five-month-long deception to pretend they had no idea of the hull's location.

[citation needed] In a section from this 2014 book titled "The Danger of Culture", retired U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Dave Oliver offers the theory based on his own experiences that a hydrogen explosion, either during or immediately following a battery charge, possibly destroyed USS Scorpion and killed her crew.

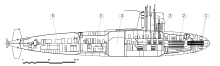

1. Sonar arrays

2. Torpedo room

3. Operations compartment

4. Reactor compartment

5. Auxiliary machinery space

6. Engine room