Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation

[23] [24][25][26][27] Notably, UV-C light is virtually absent in sunlight reaching the Earth's surface due to the absorptive properties of the ozone layer within the atmosphere.

[28] The development of UVGI traces back to 1878 when Arthur Downes and Thomas Blunt found that sunlight, particularly its shorter wavelengths, hindered microbial growth.

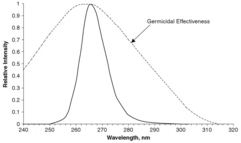

[41] Frederick Gates, in the late 1920s, offered the first quantitative bactericidal action spectra for Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus coli, noting peak effectiveness at 265 nm.

William F. Wells demonstrated in 1935 that airborne infectious organisms, specifically aerosolized B. coli exposed to 254 nm UV, could be rapidly inactivated.

Shortly after Wells' initial experiments, high-intensity UVGI was employed to disinfect a hospital operating room at Duke University in 1936.

[50] Soon, this approach was extended to other hospitals and infant wards using UVGI "light curtains", designed to prevent respiratory cross-infections, with noticeable success.

[55][56][57] This was exemplified by Wells' successful usage of upper-room UVGI between 1937 and 1941 to curtail the spread of measles in suburban Philadelphia day schools.

[58] Richard L. Riley, initially a student of Wells, continued the study of airborne infection and UVGI throughout the 1950s and 60s, conducting significant experiments in a Veterans Hospital TB ward.

[59][60][61] Despite initial successes, the use of UVGI declined in the second half of the 20th century era due to various factors, including a rise in alternative infection control and prevention methods, inconsistent efficacy results, and concerns regarding its safety and maintenance requirements.

As a result, US EPA has accepted UV disinfection as a method for drinking water plants to obtain Cryptosporidium, Giardia or virus inactivation credits.

While it is theoretically possible in a controlled environment, it is very difficult to prove and the term "disinfection" is generally used by companies offering this service as to avoid legal reprimand.

[80] Many standard UVGI systems, such as low-pressure mercury (LP-Hg) lamps, produce broad-band emissions in the UV-C range and also peaks in the UV-B band.

Precautions are commonly implemented to protect users of these UVGI systems, including: Since the early 2010s there has been growing interest in the far-UVC wavelengths of 200-235 nm for whole-room exposure.

It has also been demonstrated that far-UVC does not cause erythema or damage to the cornea at levels many times that of solar UV or conventional 254 nm UVGI systems.

[88][89][22] Exposure limits for UV, particularly the germicidal UV-C range, have evolved over time due to scientific research and changing technology.

In the 1930s and 40s, an experiment in public schools in Philadelphia showed that upper-room ultraviolet fixtures could significantly reduce the transmission of measles among students.

However, numerous professional and scientific publications have indicated that the overall effectiveness of UVGI actually increases when used in conjunction with fans and HVAC ventilation, which facilitate whole-room circulation that exposes more air to the UV source.

UV can also be used to remove chlorine and chloramine species from water; this process is called photolysis, and requires a higher dose than normal disinfection.

[108][109] Ultraviolet can also be combined with ozone or hydrogen peroxide to produce hydroxyl radicals to break down trace contaminants through an advanced oxidation process.

UV treatment compares favourably with other water disinfection systems in terms of cost, labour and the need for technically trained personnel for operation.

Water chlorination treats larger organisms and offers residual disinfection, but these systems are expensive because they need special operator training and a steady supply of a potentially hazardous material.

[citation needed] A 2006 project at University of California, Berkeley produced a design for inexpensive water disinfection in resource deprived settings.

In a somewhat similar proposal in 2014, Australian students designed a system using potato chip (crisp) packet foil to reflect solar UV radiation into a glass tube that disinfects water without power.

The radiation profile is developed from inputs such as water quality, lamp type (power, germicidal efficiency, spectral output, arc length), and the transmittance and dimension of the quartz sleeve.

System validation uses non-pathogenic surrogates such as MS 2 phage or Bacillus subtilis to determine the Reduction Equivalent Dose (RED) ability of the reactors.

Individual wastestreams to be treated by UVGI must be tested to ensure that the method will be effective due to potential interferences such as suspended solids, dyes, or other substances that may block or absorb the UV radiation.

Water passing through the flow chamber is exposed to UV rays, which are absorbed by suspended solids, such as microorganisms and dirt, in the stream.

The reduced size of LEDs opens up options for small reactor systems allowing for point-of-use applications and integration into medical devices.

[119] Low power consumption of semiconductors introduce UV disinfection systems that utilized small solar cells in remote or Third World applications.

[119] UV-C LEDs don't necessarily last longer than traditional germicidal lamps in terms of hours used, instead having more-variable engineering characteristics and better tolerance for short-term operation.