Uganda Railway

The official approach, British and local, to both slavery and free porter labour included a genuine belief that the man doing the work had real interests which deserved concern and protection.

It was decided to build the railway as quickly as possible; its construction was viewed almost as a military attack—casualties were inevitable and might be large if the objective were to be attained and momentum not lost.

[1] Before the railway's construction, the Imperial British East Africa Company had begun the Mackinnon-Sclater road, a 970-kilometre (600 mi) ox-cart track from Mombasa to Busia in Kenya, in 1890.

In December 1890, a letter from the Foreign Office to the treasury proposed constructing a railway from Mombasa to Uganda to disrupt the traffic of slaves from its source in the interior to the coast.

[3] With steam-powered access to Uganda, the British could transport people and soldiers to ensure dominance of the African Great Lakes region.

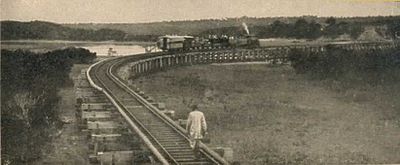

[6] Construction began at the port city of Mombasa in British East Africa in 1896 and finished at the line's terminus, Kisumu, on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria, in 1901.

Workers were sourced from villages in the Punjab and sent to Karachi on specially chartered steamers belonging to the British India Steam Navigation Company.

Hunting mainly at night, a pair of maneless male lions stalked and killed at least 28 Indian and African workers – although some accounts put the number of victims as high as 135.

Whilst the concept of cost-benefit analysis did not exist in public spending in the Victorian Era, the huge capital sums of the project nevertheless made many sceptical of the value of the investment.

This, coupled with the fatalities and wastage of the personnel constructing it through disease, tribal activity, and hostile wildlife led the Uganda Railway to be dubbed a Lunatic Line: What it will cost no words can express, What is its object no brain can suppose, Where it will start from no one can guess, Where it is going to nobody knows, What is the use of it, none can conjecture, What it will carry, there is none can define, And in spite of George Curzon's superior lecture, It is clearly naught but a lunatic line.

Years before, Joseph Chamberlain had proclaimed that, if Britain were to step away from its "manifest destiny", it would by default leave it to other nations to take up the work that it would have been seen as "too weak, too poor, and too cowardly" to have done itself.

[20] Because of the wooden trestle bridges, enormous chasms, prohibitive cost, hostile tribes, men infected by the hundreds by diseases, and man-eating lions pulling railway workers out of carriages at night, the name "Lunatic Line" certainly seemed to fit.

Through everything—through the forests, through the ravines, through troops of marauding lions, through famine, through war, through five years of excoriating Parliamentary debate, muddled and marched the railway.

In 1898 it launched the 110 ton SS William Mackinnon at Kisumu, having assembled the vessel from a "knock down" kit supplied by Bow, McLachlan and Company of Paisley in Scotland.

As the only modern means of transport from the East African coast to the higher plateaus of the interior, a ride on the Uganda Railway became an essential overture to the safari adventures which grew in popularity in the first two decades of the 20th century.

The rail journey stirred many a romantic passage, like this one from former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who rode the line to start his world-famous safari in 1909: The railroad, the embodiment of the eager, masterful, materialistic civilization of today, was pushed through a region in which nature, both as regards wild man and wild beast, does not differ materially from what it was in Europe in the late Pleistocene.

Research has shown that expectations and hopes for the transformations that the Uganda railway would bring about are similar to contemporary visions about the changes that would happen once East Africa became connected to high-speed fibre-optic broadband.

The construction also serves as the backdrop to the novel Dance of the Jakaranda (Akashic Books, 2017) by Peter Kimani, and appears early in the novel A History of Burning by Janika Oza (2023).