Huldrych Zwingli

Among his most notable contributions to the Reformation was his expository preaching, starting in 1519, through the Gospel of Matthew, before eventually using Biblical exegesis to go through the entire New Testament, a radical departure from the Catholic mass.

The religious factions of Zwingli's time debated vociferously the merits of sending young Swiss men to fight in foreign wars mainly for the enrichment of the cantonal authorities.

[13] These internal and external factors contributed to the rise of a Confederation national consciousness, in which the term fatherland (Latin: patria) began to take on meaning beyond a reference to an individual canton.

Zwingli was ordained in Constance, the seat of the local diocese, by Bishop Hugo von Hohenlandenberg, and he celebrated his first Mass in his hometown, Wildhaus, on 29 September 1506.

Zwingli defended this act in a sermon which was published on 16 April, under the title Von Erkiesen und Freiheit der Speisen (Regarding the Choice and Freedom of Foods).

[46][47] Fabri, who had not envisaged an academic disputation in the manner Zwingli had prepared for,[48] was forbidden to discuss high theology before laymen, and simply insisted on the necessity of the ecclesiastical authority.

[49][50] In September 1523, Leo Jud, Zwingli's closest friend and colleague and pastor of St Peterskirche, publicly called for the removal of statues of saints and other icons.

During the first three days of dispute, although the controversy of images and the mass were discussed, the arguments led to the question of whether the city council or the ecclesiastical government had the authority to decide on these issues.

Zwingli wrote a booklet on the evangelical duties of a minister, Kurze, christliche Einleitung (Short Christian Introduction), and the council sent it out to the clergy and the members of the Confederation.

As individual pastors altered their practices as each saw fit, Zwingli was prompted to address this disorganised situation by designing a communion liturgy in the German language.

The council secularised the church properties (Fraumünster handed over to the city of Zurich by Zwingli's acquaintance Katharina von Zimmern in 1524) and established new welfare programs for the poor.

When talks were broken off, Zwingli published Wer Ursache gebe zu Aufruhr (Whoever Causes Unrest) clarifying the opposing points of view.

[68][69] On 8 April 1524, five cantons, Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, and Zug, formed an alliance, die fünf Orte (the Five States) to defend themselves from Zwingli's Reformation.

Eck led the Catholic party while the reformers were represented by Johannes Oecolampadius of Basel, a theologian from Württemberg who had carried on an extensive and friendly correspondence with Zwingli.

[citation needed] In the case of Bern, Berchtold Haller, the priest at St Vincent Münster, and Niklaus Manuel, the poet, painter, and politician, had campaigned for the reformed cause.

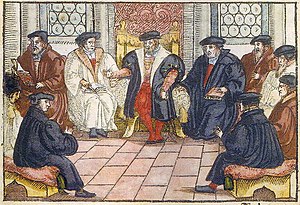

Three hundred and fifty persons participated,[71]: 144 including pastors from Bern and other cantons as well as theologians from outside the Confederation such as Martin Bucer and Wolfgang Capito from Strasbourg, Ambrosius Blarer from Constance, and Andreas Althamer from Nuremberg.

He demanded the dissolution of the Christian Alliance; unhindered preaching by reformers in the Catholic states; prohibition of the pension system; payment of war reparations; and compensation to the children of Jacob Kaiser.

Timothy George, evangelical author, editor of Christianity Today and professor of Historical Theology at Beeson Divinity School at Samford University, has refuted a long-standing misreading of Zwingli that erroneously claimed the Reformer denied all notions of real presence and believed in a memorial view of the Supper, where it was purely symbolic.

[81][82] By spring 1527, Luther reacted strongly to Zwingli's views in the treatise Dass Diese Worte Christi "Das ist mein Leib etc."

Martin Bucer tried to mediate while Philip of Hesse, who wanted to form a political coalition of all Protestant forces, invited the two parties to Marburg to discuss their differences.

Indeed, to press the literal meaning of the text even farther, it follows that Christ would have again to suffer pain, as his body was broken again—this time by the teeth of communicants.

The same motive that had moved Zwingli so strongly to oppose images, the invocation of saints, and baptismal regeneration was present also in the struggle over the Supper: the fear of idolatry.

Bern refused to participate, but after a long process, Zürich, Basel, and Strasbourg signed a mutual defence treaty with Philip in November 1530.

[89] As Zwingli was working on establishing these political alliances, Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, invited Protestants to the Augsburg Diet to present their views so that he could make a verdict on the issue of faith.

Zürich's mobilisation was slow due to internal squabbling and, on 11 October, 3500 poorly deployed men encountered a Five States force nearly double their size near Kappel.

[93] Zwingli had considered himself first and foremost a soldier of Christ; second a defender of his country, the Confederation; and third a leader of his city, Zürich, where he had lived for the previous twelve years.

He used various passages of scripture to argue against transubstantiation as well as Luther's views, the key text being John 6:63, "It is the Spirit who gives life, the flesh is of no avail".

Gottfried W. Locher writes, "The old assertion 'Zwingli was against church singing' holds good no longer ... Zwingli's polemic is concerned exclusively with the medieval Latin choral and priestly chanting and not with the hymns of evangelical congregations or choirs".

Locher then summarizes his comments on Zwingli's view of church music as follows: "The chief thought in his conception of worship was always 'conscious attendance and understanding'—'devotion', yet with the lively participation of all concerned".

2019 began the 500th anniversary of the Swiss Reformation with a conference at John Calvin University, and renewed interest in revisiting the life and impact of Zwingli.