Plantation of Ulster

Most of the land had been confiscated from the native Gaelic chiefs, several of whom had fled Ireland for mainland Europe in 1607 following the Nine Years' War against English rule.

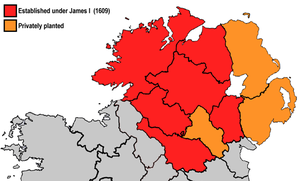

The official plantation comprised an estimated half a million acres (2,000 km2) of arable land in counties Armagh, Cavan, Fermanagh, Tyrone, Donegal, and Londonderry.

Many of the Gaelic Irish practised "creaghting" or "booleying", a kind of transhumance whereby some of them moved with their cattle to upland pastures during the summer months and lived in temporary dwellings during that time.

[27] The war fought between the native Irish Confederacy and the English Crown undoubtedly contributed to depopulation, with 60,000 reported dead by famine and attacks on the civilian population.

[31] In the 1570s, Elizabeth I authorised a privately funded plantation of eastern Ulster, led by Thomas Smith and Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex.

In 1607, O'Neill and his primary allies left Ireland to seek Spanish help for a new rebellion to restore their privileges, in what became known as the Flight of the Earls.

The rebellion prompted Arthur Chichester, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, to plan a much bigger plantation and to expropriate the legal titles of all native landowners in the province.

The principal landowners were to be "Undertakers", wealthy men from England and Scotland who undertook to import tenants from their own estates.

Veterans of the Nine Years' War (known as "Servitors") led by Arthur Chichester successfully lobbied to be rewarded with land grants of their own.

[46] From 1609 onwards, British Protestant colonists arrived in Ulster through direct importation by Undertakers to their estates and also by a spread to unpopulated areas, through ports such as Derry and Carrickfergus.

[47] Some planters settled on uninhabited and unexploited land, often building up their farms and homes on overgrown terrain that has been variously described as "wilderness" and "virgin" ground.

However, ministers chosen to serve in the plantation were required to take a course in the Irish language before ordination, and nearly 10% of those who took up their preferments spoke it fluently.

[61][page needed] Nevertheless, conversion was rare, despite the fact that, after 1621, Gaelic Irish natives could be officially classed as British if they converted to Protestantism.

Chichester wrote in 1610 that the native Irish in Ulster were "generally discontented, and repine greatly at their fortunes, and the small quantity of land left to them".

That same year, English army officer Toby Caulfield wrote that "there is not a more discontented people in Christendom" than the Ulster Irish.

[65] Historian Thomas Bartlett suggests that Irish hostility to the plantation may have been muted in the early years, as there were much fewer settlers arriving than expected.

[66] Historian Gerard Farrell writes that the plantation stoked a "smoldering resentment" in the Irish, among whom "a widespread perception persisted that they and the generation before them had been unfairly dispossessed of their lands by force and legal chicanery".

Ferrell suggests it took many years for an Irish uprising to happen because there was depopulation, because many native leaders had been removed, and those who remained only belatedly realised the threat of the plantation.

Charles I subsequently raised an army largely composed of Irish Catholics, and sent them to Ulster in preparation to invade Scotland.

In the midst of this, Gaelic Irish landowners in Ulster, led by Felim O'Neill and Rory O'More, planned a rebellion to take over the administration in Ireland.

A. T. Q. Stewart states that "The fear which it inspired survives in the Protestant subconscious as the memory of the Penal Laws or the Famine persists in the Catholic.

[76] As a result, the English Parliamentarians (or Cromwellians) were generally hostile to Scottish Presbyterians after they re-conquered Ireland from the Catholic Confederates in 1649–53.

The main beneficiaries of the postwar Cromwellian settlement were English Protestants like Sir Charles Coote, who had taken the Parliament's side over the King or the Scottish Presbyterians.

This was of particular concern to James VI of Scotland when he became King of England, since he knew Scottish instability could jeopardise his chances of ruling both kingdoms effectively.

Another wave of Scottish immigration to Ulster took place in the 1690s, when tens of thousands of Scots fled a famine (1696–1698) in the border region of Scotland.

[79] There was continuing English migration throughout this period, particularly the 1650s and 1680s, notably amongst these settlers were the Quakers from the North of England, who contributed greatly to the cultivation of flax and linen.

During the 18th century, rising Scots resentment over religious, political and economic issues fueled their emigration to the American colonies, beginning in 1717 and continuing up to the 1770s.

Scots-Irish from Ulster and Scotland and British from the borders region comprised the most numerous group of immigrants from Great Britain and Ireland to the colonies in the years before the American Revolution.

They settled first mostly in Pennsylvania and western Virginia, from where they moved southwest into the backcountry of the Upland South, the Ozarks and the Appalachian Mountains.

A. T. Q. Stewart, a protestant from Belfast, concluded: "The distinctive Ulster-Scottish culture, isolated from the mainstream of Catholic and Gaelic culture, would appear to have been created not by the specific and artificial plantation of the early seventeenth century, but by the continuous natural influx of Scottish settlers both before and after that episode ...."[84] The Plantation of Ulster is also widely seen as the origin of mutually antagonistic Catholic/Irish and Protestant/British identities in Ulster.

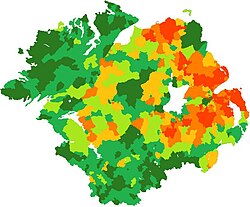

0–10% dark orange, 10–30% mid orange,

30–50% light orange, 50–70% light green,

70–90% mid green, 90–100% dark green