Unbinilium

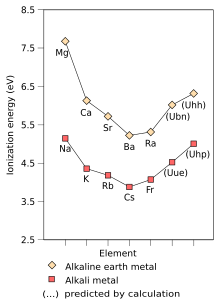

For example, unbinilium is expected to be less reactive than barium and radium, be closer in behavior to strontium, and while it should show the characteristic +2 oxidation state of the alkaline earth metals, it is also predicted to show the +4 and +6 oxidation states, which are unknown in any other alkaline earth metal.

[20] The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds.

This value was chosen as an estimate of how long it takes a nucleus to acquire electrons and thus display its chemical properties.

Tens of milligrams of these would be needed to create such targets, but only micrograms of einsteinium and picograms of fermium have so far been produced.

[53] More practical production of further superheavy elements would require bombarding actinides with projectiles heavier than 48Ca,[52] but this is expected to be more difficult.

[53] Attempts to synthesize elements 119 and 120 push the limits of current technology, due to the decreasing cross sections of the production reactions and their probably short half-lives,[54] expected to be on the order of microseconds.

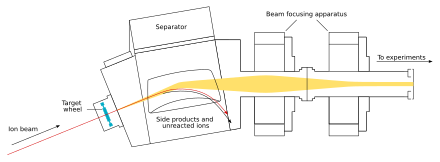

[1][55] Following their success in obtaining oganesson by the reaction between 249Cf and 48Ca in 2006, the team at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna started experiments in March–April 2007 to attempt to create unbinilium with a 58Fe beam and a 244Pu target.

[58] In April 2007, the team at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Darmstadt, Germany attempted to create unbinilium using a 238U target and a 64Ni beam:[59] No atoms were detected.

The GSI repeated the experiment with higher sensitivity in three separate runs in April–May 2007, January–March 2008, and September–October 2008, all with negative results, reaching a cross section limit of 90 fb.

Thus, 249Cf could no longer be used as a target, as it would have to be produced at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in the United States.

[73] In 2023, the director of the JINR, Grigory Trubnikov, stated that he hoped that the experiments to synthesise element 120 will begin in 2025.

This was an unexpectedly good result; the aim had been to experimentally determine the cross-section of a reaction with 54Cr projectiles and prepare for the synthesis of element 120.

[79] The team at the Heavy Ion Research Facility in Lanzhou, which is operated by the Institute of Modern Physics (IMP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, also plans to synthesise elements 119 and 120.

The 1979 IUPAC recommendations temporarily call it unbinilium (symbol Ubn) until it is discovered, the discovery is confirmed and a permanent name chosen.

This concept, proposed by University of California professor Glenn Seaborg, explains why superheavy elements last longer than predicted.

Several experiments have been performed between 2000 and 2008 at the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions in Dubna studying the fission characteristics of the compound nucleus 302Ubn*.

[89] In 2008, the team at GANIL, France, described the results from a new technique which attempts to measure the fission half-life of a compound nucleus at high excitation energy, since the yields are significantly higher than from neutron evaporation channels.

The team studied the nuclear fusion reaction between uranium ions and a target of natural nickel:[90][91] The results indicated that nuclei of unbinilium were produced at high (≈70 MeV) excitation energy which underwent fission with measurable half-lives just over 10−18 s.[90][91] Although very short (indeed insufficient for the element to be considered by IUPAC to exist, because a compound nucleus has no internal structure and its nucleons have not been arranged into shells until it has survived for 10−14 s, when it forms an electronic cloud),[92] the ability to measure such a process indicates a strong shell effect at Z = 120.

At lower excitation energy (see neutron evaporation), the effect of the shell will be enhanced and ground-state nuclei can be expected to have relatively long half-lives.

[94] Being the second period 8 element, unbinilium is predicted to be an alkaline earth metal, below beryllium, magnesium, calcium, strontium, barium, and radium.

Each of these elements has two valence electrons in the outermost s-orbital (valence electron configuration ns2), which is easily lost in chemical reactions to form the +2 oxidation state: thus the alkaline earth metals are rather reactive elements, with the exception of beryllium due to its small size.

[1] The main reason for the predicted differences between unbinilium and the other alkaline earth metals is the spin–orbit (SO) interaction—the mutual interaction between the electrons' motion and spin.

The SO interaction is especially strong for the superheavy elements because their electrons move faster—at velocities comparable to the speed of light—than those in lighter atoms.

Computational chemists understand the split as a change of the second (azimuthal) quantum number l from 1 to 1/2 and 3/2 for the more-stabilized and less-stabilized parts of the 7p subshell, respectively.

[1] This stabilization of the outermost s-orbital (already significant in radium) is the key factor affecting unbinilium's chemistry, and causes all the trends for atomic and molecular properties of alkaline earth metals to reverse direction after barium.

[96] Unbinilium should be a solid at room temperature, with melting point 680 °C:[98] this continues the downward trend down the group, being lower than the value 700 °C for radium.

[3][2] The chemistry of unbinilium is predicted to be similar to that of the alkaline earth metals,[1] but it would probably behave more like calcium or strontium[1] than barium or radium.

[4] Many unbinilium compounds are expected to have a large covalent character, due to the involvement of the 7p3/2 electrons in the bonding: this effect is also seen to a lesser extent in radium, which shows some 6s and 6p3/2 contribution to the bonding in radium fluoride (RaF2) and astatide (RaAt2), resulting in these compounds having more covalent character.

On the other hand, their metal–metal bond-dissociation energies generally increase from Ca2 to Ba2 and then drop to Ubn2, which should be the most weakly bound of all the group 2 homodiatomic molecules.