Unclean spirit

[11] In the New Testament, the Greek modifier akatharton, although sometimes translated in context as "evil,"[12] means more precisely "impure, not purified," and reflects a concern for ritual purification shared with or derived from Judaism, though reinterpreted.

[16] It can be difficult to distinguish between a demon and an unclean or evil spirit in Judaic theology or contemporary scholarship; both entities like to inhabit wild or desolate places.

[18] The se’irim or śa‘ir are goat-demons or "hairy demons"[19] (sometimes translated as "satyrs") associated with other harmful supernatural beings and with ruins, i.e., human structures that threaten to revert to the wild.

[20] The demonic figure Azazel, depicted with goat-like features and in one instance as an unclean bird, is consigned to desert places as impure.

[21] The Babylonian Talmud[22] says that a person who wanted to attract an impure spirit might fast and spend the night in a cemetery;[23] in the traditional religions of the Near East and Europe, one ritual mode for seeking a divinely inspired revelation or prophecy required incubation at the tomb of an ancestor or hero.

[25] To pneuma to akatharton appears in the Septuagint at Zechariah 13:2,[26] where pseudoprophetai ("false prophets") speak in the name of Yahweh but are possessed by an unclean spirit.

A tradition of Solomonic exorcism continued into medieval Europe; an example is recorded by Gregory the Thaumaturge: "I adjure you all unclean spirits by Elohim, Adonai, Sabaoth, to come out and depart from the servant of God.

In the Greek New Testament, 20 occurrences of pneuma akatharton (singular and plural) are found in the Synoptic Gospels, Acts of the Apostles, and the Book of Revelation.

"It was certainly not very kind to the pigs," the philosopher Bertrand Russell remarked, "to put the devils into them and make them rush down the hill to the sea.

[55] Although the vaginal reception of the pneuma may strike the 21st-century reader as strange, fumigation was a not uncommon gynecological regimen throughout the Hippocratic Corpus and was employed as early as 1900–1500 BC in ancient Egyptian medicine.

[59] As a form of ritual purification, fumigation was intended to enhance the Pythia's receptivity to divine communication; to the men of the Church, the open vagina that served no reproductive purpose was an uncontrolled form of sexuality that invited demonic influence, necessarily rendering the Pythia's prophecies false.

In Acts 16:16–18, after Paul and Silas visit a woman of Thyatira, they are greeted on their way to synagogue by a "working girl" (paidiskê), a slave who has earned a reputation as a gifted diviner; she is said to have a pneuma pythona, not akatharton or poneron, though the spirit is presumed to be evil.

Although it is unclear why a Christian would dispute the truth of the paidiskê's message, and although Jesus himself had said "anyone who is not against you is for you" (see above and Luke 9:49–50), Paul eventually grows annoyed and commands the pneuma to leave her.

[66] Although both are forms of divination, Plato had distinguished the two: the mantis became the mouthpiece of the god through possession, but the "prophecy of interpretation" required specialized knowledge of how to read signs and omens and was considered a rational process.

[67] Plutarch gives Pythones as a synonym for engastrimythoi ("belly-talkers" or "ventriloquists"), a suspect type of mantic who employed trickery in projecting a voice, sometimes through a device such as a mechanical snake.

The snake was probably the chosen medium because of its association in myth with Delphi, where Apollo killed the serpent (the Python) to establish his own oracle there.

The implication of sexual union between the god and a mortal woman is again viewed as a dangerous deception.In one of his epistles to Timothy,[72] Paul defines apostates as those who are drawn to "deceiving" or "seductive" spirits (pneumasin planois) and demonic teachings (didaskaliais daimoniôn).

These pneumata plana are also found frequently in the apocryphal Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, where they threaten to lead astray the Israelites into varieties of immorality.

The incident has been examined at length from the perspective of feminist theology by Francis Taylor Gench, who views it as both healing and liberating; Jesus goes on to say that the woman has been freed from a kind of bondage to Satan.

It thus differs from most possessing demons, who are given to taunts and mockery (diabolos, the origin of both "diabolic" and "Devil," means "slanderer" in Greek).

This demonic possession manifests itself through symptoms that resemble epilepsy, as is suggested also by Matthew 17:15, who uses a form of the colloquial verb seleniazetai ("moonstruck") for the condition.

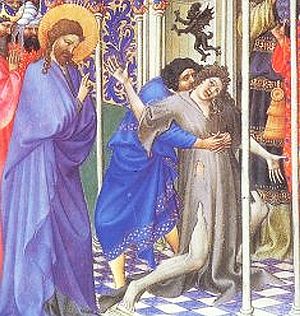

[79]Before Jesus, exorcism had been conducted by a trained practitioner who offered a diagnosis and administered a ritual usually employing spoken formularies, amulets or other objects, or compounds of substances resembling pharmacological recipes of the time.

In the period of post-Apostolic Christianity[broken anchor], baptism and the Eucharist required the prior riddance of both unclean spirits and illness.

[85] Because the possessing demon was conceptualized as a pneuma or spiritus, each of which derives from a root meaning "breath," one term for its expulsion was exsufflation, or a "blowing out.

Gyllou, a type of reproductive demon that appears on Aramaic amulets in late antiquity, is described in a Greek text as "abominable and unclean" (μιαρὰ καὶ ἀκάθαρτος, miara kai akathartos),[89] and is the object of a prayer to the Virgin Mary asking for protection.

[90] In his Decretum, Burchard of Worms asserts that "we know that unclean spirits (spiritus immundi) who fell from the heavens wander about between the sky and earth," drawing on the view expressed in the Moralia in Job of Gregory I.

The fear is not treated as groundless; rather, Burchard recommends Christ and the sign of the cross as protection, rather than reliance on the cock's crow.

The Milanese rite prescribes exsufflation: Exsufflat in faciem ejus in similitudinem crucis dum dicit ("Breathe out onto [the subject's] face in the likeness of the cross while speaking").

The 9th-century Stowe Missal preserves an early Celtic formula as procul ergo hinc, iubente te, domine, omnis spiritus immundus abscedat ("Therefore at your bidding, Lord, let every unclean spirit depart far from here").

[94] In a Latin version of The Blessing of the Waters on the Eve of Epiphany performed in Rome and recorded at the turn of the 19th–20th centuries, the unclean spirit is commanded per Deum vivum ("by the Living God").