Underground Railroad

[16] Eric Foner wrote that the term "was perhaps first used by a Washington newspaper in 1839, quoting a young slave hoping to escape bondage via a railroad that 'went underground all the way to Boston'".

[17][18] Dr. Robert Clemens Smedley wrote that following slave catchers' failed searches and lost traces of fugitives as far north as Columbia, Pennsylvania, they declared in bewilderment that "there must be an underground railroad somewhere," giving origin to the term.

[19] Scott Shane wrote that the first documented use of the term was in an article written by Thomas Smallwood in the August 10, 1842, edition of Tocsin of Liberty, an abolitionist newspaper published in Albany.

The law made it easier for slaveholders and slave catchers to capture African Americans and return them to slavery, and in some cases allowed them to enslave free blacks.

In North Carolina freedom seekers put turpentine on their shoes to prevent slave catchers' dogs from tracking their scents, in Texas escapees used paste made from a charred bullfrog.

It consisted of meeting points, secret routes, transportation, and safe houses, all of them maintained by abolitionist sympathizers and communicated by word of mouth, although there is also a report of a numeric code used to encrypt messages.

[55] In addition, author Diane Miller states: "Traditionally, historians have overlooked the agency of African Americans in their own quest for freedom by portraying the Underground Railroad as an organized effort by white religious groups, often Quakers, to aid 'helpless' slaves."

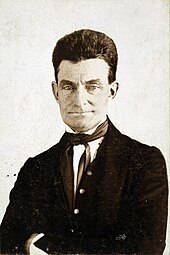

The actions of real historical figures such as Harriet Tubman, Thomas Garrett, and Levi Coffin are exaggerated, and Northern abolitionists who guided the enslaved to Canada are hailed as the heroes of the Underground Railroad.

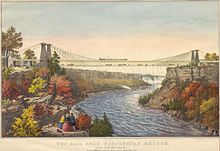

[56][57] The Underground Railroad benefited greatly from the geography of the U.S.–Canada border: Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and most of New York were separated from Canada by water, over which transport was usually easy to arrange and relatively safe.

The main route for freedom seekers from the South led up the Appalachians, Harriet Tubman going via Harpers Ferry, through the highly anti-slavery Western Reserve region of northeastern Ohio to the vast shore of Lake Erie, and then to Canada by boat.

One of the most famous and successful conductors (people who secretly traveled into slave states to rescue those seeking freedom) was Harriet Tubman, a woman who escaped slavery.

[75][76] Due to the risk of discovery, information about routes and safe havens was passed along by word of mouth, although in 1896 there is a reference to a numerical code used to encrypt messages.

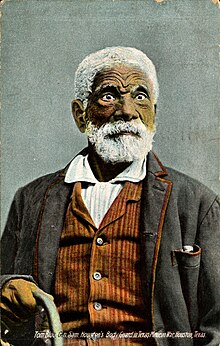

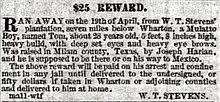

Southern newspapers of the day were often filled with pages of notices soliciting information about fugitive slaves and offering sizable rewards for their capture and return.

Historical archeologist Dan Sayer says that historians downplay the importance of maroon settlements and place valor in white involvement in the Underground Railroad, which he argues shows a racial bias, indicating a "...reluctance to acknowledge the strength of black resistance and initiative.

[96][97] Beginning in the 16th century, Spaniards brought enslaved Africans to New Spain, including Mission Nombre de Dios in what would become the city of St. Augustine in Spanish Florida.

In Monclova, Mexico a border official took up a collection in the town for a family in need of food, clothing, and money to continue on their journey south and out of reach of slave hunters.

[100] Knowing the repercussions of running away or being caught helping someone runaway, people were careful to cover their tracks, and public and personal records about fugitive slaves are scarce.

The Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression initiated a Federal Writers' Project to document slave narratives, including those who settled in Mexico.

[113] Roseann Bacha-Garza, of the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, has managed historical archeology projects and has researched the incidence of enslaved people who fled to Mexico.

[104][114] Mekala Audain has also published a chapter titled "A Scheme to Desert: The Louisiana Purchase and Freedom Seekers in the Louisiana-Texas Borderlands, 1804–1806" in the edited volume In Search of Liberty: African American Internationalism in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World.

Territorial governor William Hull offered Peter Denison, an enslaved man, "a written license" allowing him to form a militia company of free Blacks and escaped slaves.

[132][133][134] From 1821 to 1861, freedom seekers escaped from the Southeastern slave states of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida to the Bahamas on a secret route called the "Saltwater Railroad."

[141][142][143][144] A few weeks after the fugitive slave law passed, Black populations in Northern cities declined due to formerly enslaved African Americans migrating to Canada in fear they might be captured and re-enslaved.

[146] During the American Civil War, the Union Army captured Southern towns in Beaufort, South Carolina, St. Simons Island, Georgia, and other areas and setup encampments.

[151] On May 12, 1862, Robert Smalls and sixteen enslaved people escaped from slavery during the Civil War on a Confederate ship and sailed it out the Charleston Harbor to a Union blockade in South Carolina.

In 1861, three enslaved men in Norfolk, Virginia, Shepard Mallory, Frank Baker, and James Townsend, escaped from slavery and fled to Union lines at Fort Monroe.

An article from the National Trust for Historical Preservation explains: "...Butler realized the absurdity of honoring the Fugitive Slave Law, which dictated that he return the three runaways to their owner.

After the passage of this act, freedom seekers from Virginia and Maryland escaped and found freedom in the District of Columbia, and by 1863, there were 10,000 refugees (former runaway slaves) in the city and their numbers doubled the Black population in Washington, D.C.[157][158] During the war, enslaved people living near Beaufort County, South Carolina escaped from slavery and fled to Union lines in Beaufort because African Americans in the county were freed from slavery after the Battle of Port Royal on November 7, 1861 when the plantation owners fled the area after the arrival of the Union Navy and Army.

To accommodate the freedom seekers, general Grenville M. Dodge established the Corinth Contraband Camp with homes, schools, hospitals, churches, and paid employment for African Americans.

Similarly, some popular, nonacademic sources claim that spirituals and other songs, such as "Steal Away" or "Follow the Drinking Gourd", contained coded information and helped individuals navigate the railroad.