United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves

The Portuguese Prince Regent (the future King John VI), with his incapacitated mother (Queen Maria I of Portugal) and the Royal Court, fled to the colony of Brazil in 1808.

On the other hand, leading Brazilian courtiers pressed for the elevation of Brazil from the rank of a colony, so that they could enjoy the full status of being nationals of the mother-country.

After the Liberal Revolution of 1820 in Portugal, the King left Brazil and returned to the European portion of the United Kingdom, arriving in Lisbon on 4 July 1821.

As for the King, upon his arrival in Lisbon, he behaved as though he accepted the new political settlement that resulted from the Liberal Revolution (a posture he would maintain until mid-1823), but the powers of the Crown were severely limited.

A Council of Regency that had been elected by the Cortes to govern Portugal in the wake of the Revolution – and that replaced by force the previous governors that administered the European portion of the United Kingdom by royal appointment – handed back the reins of government to the Monarch on his arrival in Lisbon, but the King was now limited to the discharge of the Executive branch, and had no influence over the drafting of the Constitution or over the actions of the Cortes.

They alleged that once the provisions approved by the Cortes were enacted and enforced, Brazil, although formally remaining a part of the transatlantic monarchy, would be in reality returned to the condition of a Colony.

Faced with that scenario, Brazilian independentists managed to convince Prince Pedro to stay in Brazil against the orders of the Cortes, that demanded his immediate return.

The Prince's decision not to obey the decrees of the Cortes that demanded this return, and instead to stay in Brazil as its Regent was solemnly announced on 9 January 1822, in reply to a formal petition from the city council of Rio de Janeiro.

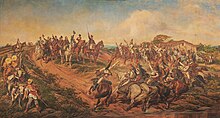

By defying explicit orders that demanded his return to Europe, Pedro escalated the events that would lead to the separation of Brazil from the United Kingdom, and hastened the crucial moment of the Proclamation of Independence.

Prince Pedro, acting on the advice of his newly convened Council, embraced those demands, and issued a decree on 13 June 1822 summoning elections for a Brazilian Constituent Assembly.

News of further attempts of the Portuguese Cortes aimed at dissolving Prince Pedro's Regency led directly to the Brazilian Proclamation of Independence.

On 4 October, acting as the Cortes had directed, the Portuguese King signed at the Royal Palace of Queluz a Charter of Law promulgating the text of the Constitution and ordering its execution by all his subjects throughout the United Kingdom.

This Charter of Law, containing the full text of the Constitution, including the signatures of the members of the Cortes and the King's instrument of assent, was published on the following day, 5 October 1822.

Also, in the context of the struggle to sustain the newly declared independence of Brazil, and to seek recognition for the Empire, the religious act of coronation would establish Emperor Pedro I as an anointed monarch, crowned by the Catholic Church.

The Portuguese initially refused to recognize Brazil as a sovereign state, treating the whole affair as a rebellion and attempting to preserve the United Kingdom.

However, military action was never close to Rio de Janeiro, and the main battles of the independence war took place in the Northeastern region of Brazil.

Under British pressure, Portugal eventually agreed to recognize Brazil's independence in 1825, thus allowing the new country to establish diplomatic ties with other European powers shortly thereafter.

Since a coup d'etát on 3 June 1823 the Portuguese King John VI had already abolished the Constitution of 1822 and dissolved the Cortes, thus reversing the Liberal Revolution of 1820.

The second act of recognition was materialized in a Treaty of Peace signed in Rio de Janeiro on 29 August 1825, by means of which Portugal again recognized the independence of Brazil.

King John VI wanted to "save face" by giving the impression that Portugal was voluntarily conceding independence to Brazil, and not just recognizing a fait accompli.

In the 13 May 1825 Letters Patent, King John recited the polity creating acts of his predecessors and of other sovereigns of Europe, recited his own desire to promote the happiness of all the peoples over which he ruled, and proceeded to declare and enact that from thenceforth the Kingdom of Brazil would be an Empire, and that the Empire of Brazil would be separate from the Kingdoms of Portugal and the Algarves in both internal and foreign affairs; that he, John, therefore took for himself the title of Emperor of Brazil and King of Portugal and the Algarves, to which would follow the other titles of the Portuguese Crown; that the title of "Prince or Princess Imperial of Brazil, and Royal of Portugal and the Algarves" would be vested in the heir or heiress presumptive of the imperial and royal Crowns; that since the succession of both the imperial and royal Crowns belonged to his son, "Prince Dom Pedro", he, King John, at once, "by this same act and letters patent", ceded and transferred to Pedro, from thenceforth, of his "own free will", the full sovereignty of the Empire of Brazil, for Pedro to govern it, assuming at once the title Emperor of Brazil, keeping at the same time the title of Prince Royal of Portugal and the Algarves, while John reserved for himself the same title of Emperor, and the position of King of Portugal and the Algarves, with the full sovereignty of the said Kingdoms (of Portugal and the Algarves).

The new Brazilian Government therefore made the establishment of peaceful relations and diplomatic ties with Portugal conditional on the signature of a bilateral treaty between the two Nations.

The treaty between the Empire of Brazil and the Kingdom of Portugal on the recognition of Brazilian independence, signed in Rio de Janeiro on 29 August 1825, finally entered into force on 15 November 1825 upon the exchange of the instruments of ratification in Lisbon.

Thus, by a separate convention that was signed on the same occasion as the Treaty on the Recognition of Independence, Brazil agreed to pay Portugal two million pounds in damages.

Before his abdication, on 26 April, King Pedro confirmed the Regency of Portugal that had been established by his father during his final illness, and that was led by the Infanta Isabel Maria, his sister.

Charles Stuart arrived in Lisbon on 2 July 1826 and presented the acts signed by King Pedro IV to the Government of Portugal, including his original deed of abdication of the Portuguese Throne.

Although Pedro's abdication of the Portuguese Crown to Maria II was provided for even in the Constitution issued on 29 April 1826, the original deed of abdication, signed on 2 May 1826 contained conditions; however, those conditions were subsequently waived, as the abdication was later declared final, irrevocable, accomplished and fully effective by a decree issued by Pedro on 3 March 1828,[3] just a few months before Infante Miguel's usurpation of the Throne and the start of the Portuguese Civil War (in accordance with a decree issued on 3 September 1827, Infante Miguel replaced Infanta Isabel Maria as Regent of Portugal on 26 February 1828, and he initially agreed to govern in the name of the Queen, but on 7 July 1828 he had himself proclaimed King with retroactive effect, assuming the title of Miguel I; Maria II would only be restored to the Throne in 1834, at the conclusion of the Civil War).

However, the question was all important because, in the event that Emperor Pedro II died before producing descendants, the Crown of the independent Empire of Brazil could end up coming to the Queen of Portugal, thus recreating a personal union between the two monarchies.

In order to settle that question, the Brazilian General Assembly adopted a statute, signed into law by the Regent on behalf of Emperor Pedro II on 30 October 1835, declaring Queen Maria II of Portugal had lost her succession rights to the Crown of Brazil, due to her condition as a foreigner, so that she and her descendants were excluded from the Brazilian line of succession; ruling that Princess Januária and her descendants were therefore first in line to the Throne after Emperor Pedro II and his descendants, and decreeing that, accordingly, Princess Januária, as the then heiress presumptive of the Brazilian Crown, should be recognized as Princess Imperial.

Thus, the abdication of the Portuguese Crown by Brazilian Emperor Pedro I terminated the brief 1826 personal union and separated the monarchies of Portugal and Brazil, and that abdication, coupled with the exclusion of the new Portuguese Queen, Maria II, from the Brazilian line of succession, broke the last remaining ties of political union between the two Nations, securing the preservation of the independence of Brazil and putting to an end all hopes of the rebirth of a Luso-Brazilian United Kingdom.