United States incarceration rate

[7] Corrections (which includes prisons, jails, probation, and parole) cost around $74 billion in 2007 according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS).

[8][9] According to the Justice Expenditures and Employment in the United States, 2017 report release by BJS, it is estimated that county and municipal governments spent roughly US$30 billion on corrections in 2017.

[10][11] As of their March 2023 publication, the Prison Policy Initiative, a non-profit organization for decarceration, estimated that in the United States, about 1.9 million people were or are currently incarcerated.

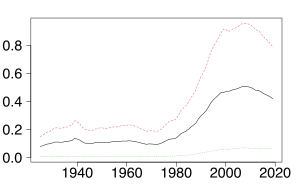

[28] In the twenty-five years since the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, the United States penal population rose from around 300,000 to more than two million.

In comparison to countries with similar percentages of immigrants, Germany has an incarceration rate of 67 per 100,000 population (as of June 2022),[34] Italy is 97 per 100,000 (as of November 2022),[35] and Saudi Arabia is 207 per 100,000 (as of 2017).

[36] When compared to other countries with a zero tolerance policy for illegal drugs, the rate of Russia is 304 per 100,000 (as of November 2022),[37] Kazakhstan is 184 per 100,000 (as of July 2022),[38] Singapore is 169 per 100,000 (as of December 2021),[39] and Sweden is 74 per 100,000 (as of January 2022).

The same report found that longer prison sentences were the main driver of increasing incarceration rates since 1990.

[citation needed] The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 may have had a minor effect on mass incarceration.

[53] The Brookings Institution reconciles the differences between Alexander and Pfaff by explaining two ways to look at the prison population as it relates to drug crimes, concluding "The picture is clear: Drug crimes have been the predominant reason for new admissions into state and federal prisons in recent decades" and "rolling back the war on drugs would not, as Pfaff and Urban Institute scholars maintain, totally solve the problem of mass incarceration, but it could help a great deal, by reducing exposure to prison.

[56] After the passage of Reagan's Anti-Drug Abuse Act in 1986, incarceration for non-violent offenses dramatically increased.

The Act imposed the same five-year mandatory sentence on those with convictions involving crack as on those possessing 100 times as much powder cocaine.

[50][57] This had a disproportionate effect on low-level street dealers and users of crack, who were more commonly poor blacks, Latinos, the young, and women.

[62] According to the American Civil Liberties Union, "Even when women have minimal or no involvement in the drug trade, they are increasingly caught in the ever-widening net cast by current drug laws, through provisions of the criminal law such as those involving conspiracy, accomplice liability, and constructive possession that expand criminal liability to reach partners, relatives and bystanders.

According to Dorothy E. Roberts, the explanation is that poor women, who are disproportionately black, are more likely to be placed under constant supervision by the State to receive social services.

This has resulted in distrust from Black individuals towards aspects of the legal system such as police, courts, and heavy sentences.

[67] Despite a general decline in crime, the massive increase in new inmates due to drug offenses ensured historically high incarceration rates during the 1990s, with New York City serving as an example.

A significant contributing factor to these figures are the racially and economically segregated neighborhoods that account for the majority of the Black prison population.

[76] In the 1980s, the rising number of people incarcerated as a result of the War on Drugs and the wave of privatization that occurred under the Reagan Administration saw the emergence of the for-profit prison industry.

[80][81] In a 2011 report by the ACLU, it is claimed that the rise of the for-profit prison industry is a "major contributor" to "mass incarceration," along with bloated state budgets.

[82] Louisiana, for example, has the highest rate of incarceration in the world with the majority of its prisoners being housed in privatized, for-profit facilities.

[83] A 2013 Bloomberg report states that in the past decade the number of inmates in for-profit prisons throughout the U.S. rose 44 percent.

[82]In January 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden signed an executive order directing the Department of Justice (DOJ) to begin phasing out its contracts with private federal prisons.

[93] As of March 2021, the private prison population of the United States has seen a 16% decline since reaching its peak in 2012 with 137,000 people incarcerated.

Constructing Crime: Perspectives on Making News and Social Problems is a book collecting together papers on this theme.

[98] The researchers say that the jump in incarceration rate from 0.1% to 0.5% of the United States population from 1975 to 2000 (documented in the figure above) was driven by changes in the editorial policies of the mainstream commercial media and is unrelated to any actual changes in crime.

That allowed media company executives to maintain substantially the same audience while slashing budgets for investigative journalism and filling the space from the police blotter, which tended to increase and stabilize advertising revenue.

News media thrive on feeding frenzies (such as missing white women) because they tend to reduce production costs while simultaneously building an audience interested in the latest development in a particular story.

"[T]he dynamics of competitive journalism created a media feeding frenzy that found news workers 'snatching at shocking numbers' and 'smothering reports of stable or decreasing use under more ominous headlines.

Beale found that the more media attention a criminal case is given, the greater the incentive for prosecutors and judges to pursue harsher sentences.

[citation needed] Less media coverage means a greater chance of a lighter sentence or that the defendant may avoid prison time entirely.