United States v. More

Benjamin More, a justice of the peace in the District of Columbia, argued that the repeal of statutory provisions authorizing compensation for his office violated the salary-protection guarantees for federal judges in Article Three of the United States Constitution.

Below, a divided panel of the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia had sided with More, interpreted the repeal act prospectively, and sustained his demurrer to the criminal indictment for the common law crime of exacting illegal fees under color of office.

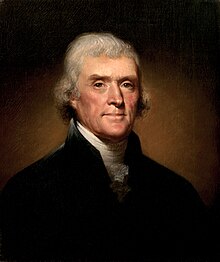

Immediately after his inauguration, Jefferson instructed his Secretary of State, James Madison, to stop delivery on all outstanding commissions.

[8] The following day, the House impeached Justice Samuel Chase, but six Democratic-Republicans crossed party lines in the Senate to prevent his conviction by a single vote.

[15] Justices of the peace were authorized to "inflict whipping, imprisonment, and fine as high as 500 pounds of tobacco" and to hear civil cases with an amount in controversy up to $20.

"[14] A March 3, 1801 amendment to the Organic Act provided that: "[T]he magistrates, to be appointed for the said district, shall be and they are hereby constituted a board of commissioners within their respective counties, and shall possess and exercise the same powers, perform the same duties, receive the same fees and emoulments [sic?

"[29] Senator (and future Supreme Court justice) William Paterson noticed the lack of provision for criminal appeals in preliminary notes and a draft outline of a speech he gave on June 23, 1789.

[30] According to Rossman, Paterson may have viewed the inability of the government to appeal (to a court in the nation's capitol) as a "protection for ordinary citizens.

[34] In Ex parte Bollman (1807), the Court explained that its jurisdiction in Hamilton could only have been exercised via original habeas under § 14 of the Judiciary Act of 1789.

[35] Second, in United States v. Lawrence (1795), the Court declined to issue a writ of mandamus to compel a district judge to order the arrest of a deserter of the French navy.

[41] According to O'Fallon, "More appears to have been a man of moderate Jeffersonian sentiments and attachments, who nonetheless joined in a Federalist defense of judicial independence.

[22] "More has all the markings of a trumped-up case, manufactured to present the Supreme Court with the issues of principle raised by the repeal, without the embarrassment of direct conflict with the Executive.

"[43] More was indicted by the Grand Inquest for the County of Washington, during its July term, for taking unlawful fees for his services as a justice of the peace.

"[56] The Organic Act provided that the laws of Maryland and Virginia would continue in force in the portions of the district ceded from those states.

[48] Cranch, joined by Marshall, sustained More's demurrer based on the Compensation Clause of Article Three of the United States Constitution.

"[58] Contemporary media accounts reported that the circuit court had held that fee-elimination provision of the May 23, 1802 act unconstitutional, rather than interpreting it as prospective.

[60] Chief Judge Kilty's dissent noted the recent confirmation of the principle of judicial review in Marbury v. Madison.

"[56] Kilty briefly argued that More was not an Article III judge and that the fees in question were not compensation received at "times Stated.

"[56] "[W]hen congress, in exercising exclusive legislation over this territory, enact laws to give or to take away the fees of the justices of the peace, such laws cannot be tested by a provision in the constitution, evidently applicable to the judicial power of the whole United States, and containing restrictions which cannot, in their nature, affect the situation of the justices, or the nature of the compensation.

"[56] He admitted that, even within the federal district, Congress was Mason argued the appeal of the United States before the Supreme Court.

[63] According to O'Fallon, due to the President's power to remove most appointees from office, this could only have been a reference to the Good Behavior Clause of Article Three.

"[59] Mason countered that Marbury only held that justices of the peace were entitled to hold their offices for five years of good behavior.

"[66] On February 13, sua sponte, Chief Justice Marshall raised his doubts to the Court's jurisdiction to entertain criminal appeals.

"[69] Mason acknowledged that, under Clarke v. Bazadone (1803),[70] the Supreme Court's appellate jurisdiction required an affirmative grant by Congress.

Said Mason: Chief Justice Marshall replied that, if Congress had made no provision for appeals of any kind to the Supreme Court, "your argument would be irresistible.

"[44] On March 2, 1805, writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice John Marshall dismissed the writ of error for want of jurisdiction.

[78] Marshall noted that "it has never been supposed, that a decision of a circuit court could be reviewed, unless the matter in dispute should exceed the value of 2,000 dollars.

"[83] The Court summarily rejected Lee's argument: "we are unanimously of opinion, that it is a civil cause: It is a process of the nature of a libel in rem; and does not, in any degree, touch the persons of the offender.

"[100] Given that Justice Samuel Chase was acquitted by the Senate in his impeachment case on March 1, 1805, the day before the release of the More decision, "[o]ne can imagine John Marshall passing a sigh of relief as he handed down the judgment in More.

"[101] "[T]he dismissal of More marked the end of Federalist efforts to obtain a Supreme Court ruling, directly or by implication, that the repeal of the 1801 Judiciary Act was unconstitutional.