County of Oneida v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York State

[2] Since then, Justices William O. Douglas and Potter Stewart had departed, replaced by John Paul Stevens and Sandra Day O'Connor.

[6] The case was initiated by George Shattuck of Bond, Schoeneck & King(BS&K), on a contingency fee basis rather than as a pro bono matter.

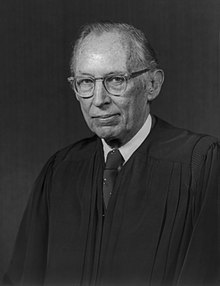

[15] The majority opinion by Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr. recognized the Oneida's federal common law cause of action, and rejected all the counties' affirmative defenses.

[16] The court concluded: [W]e hold that the Oneidas can maintain this action for violation of their possessory rights based on federal common law.

"[18] Because the Act contained no remedial provisions, and because subsequent Congressional enactments contemplated possessory land suits by Indians, the Court found that preemption was not indicated.

[19] The court reviewed its recent aboriginal title decisions, and reiterated its statement in Oneida I that the Act merely "put in statutory form what was or came to be the accepted rule.

"[22] Reviewing Congressional actions in the context of the Indian Claims Commission, the Court concluded that "It would be a violation of Congress' will were we to hold that a state statute of limitations period should be borrowed in these circumstances.

"[24] The same footnote cited Ewert v. Bluejacket, 259 U.S. 129 (1922) for the proposition that laches "cannot properly have application to give vitality to a void deed and to bar the rights of Indian wards in lands subject to statutory restrictions.

"[24] In its final footnote, the majority noted that, on "[t]he question whether equitable considerations should limit the relief available to the present day Oneida Indians .

"[25] The counties advanced the theory that the causes of action under Nonintercourse Acts of 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, and 1802 (unlike the final 1833 version) abated upon the expiration of the statutes.

[29] The Court concluded by remarking upon the "potential consequences of affirmance," arguing that "this litigation makes abundantly clear the necessity for congressional action" to extinguish Indian title by statute.

As our opinion indicates, however, neither petitioners nor we have found any applicable statute of limitations or other relevant legal basis for holding that the Oneidas' claims are barred or otherwise have been satisfied.

[34] Specifically, they cited "[t]hree decisions of this Court illustrate the application of the doctrine of laches to actions seeking to set aside conveyances made in violation of federal law.

"[35] Moreover, the dissenters quoted Lewis v. Marshall, 30 U.S. 470 (1831), for the proposition that: The best interests of society require that causes of action should not be deferred an unreasonable time.

[37] The following year, McCurn denied cross-motions for relief from the judgment–seeking to correct various mathematical errors previously made by Judge Port—due to a pending appeal before the Second Circuit.

[39] Another Oneida claim, challenging the pre-constitutional conveyance of another 6-million-acre (24,000 km2) tract, was rejected by the Second Circuit in 1988, on the grounds that the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783 had neither the authority nor the intent to limit the acquisition of Indian lands within the borders of the states.

Instead, they began to purchase land within the claim area in fee simple, asserting sovereignty over the re-acquired parcels and refusing to pay property tax.

In City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York (2005), the Supreme Court held that laches barred the re-assertion of sovereignty over ancestral land re-acquired in fee simple; the Court did not consider whether the original aboriginal title over the disputed parcels was validly extinguished, and thus did not disturb its holding in Oneida II.

[43] In a similar suit by a different tribe, the Second Circuit adopted the view of the four dissenting Oneida II justices in Cayuga Indian Nation of New York v. Pataki (2005).