Ununennium

Ununennium and Uue are the temporary systematic IUPAC name and symbol respectively, which are used until the element has been discovered, confirmed, and a permanent name is decided upon.

The Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia, plans to make an attempt at some point in the future, but a precise date has not been released to the public.

[20] The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds.

This value was chosen as an estimate of how long it takes a nucleus to acquire electrons and thus display its chemical properties.

However, its range is very short; as nuclei become larger, its influence on the outermost nucleons (protons and neutrons) weakens.

[i] Spontaneous fission, however, produces various nuclei as products, so the original nuclide cannot be determined from its daughters.

[j] Elements 114 to 118 (flerovium through oganesson) were discovered in "hot fusion" reactions at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Russia.

[53] An attempt to make element 119 from calcium-48 and less than a microgram of einsteinium was made in 1985 at the superHILAC accelerator at Berkeley, California, but did not succeed.

[54] More practical production of further superheavy elements requires projectiles heavier than 48Ca,[52] but this makes the reaction more symmetric[55] and gives it a smaller chance of success.

[53] Attempts to synthesize element 119 push the limits of current technology, due to the decreasing cross sections of the production reactions and the probably short half-lives of produced isotopes,[56] expected to be on the order of microseconds.

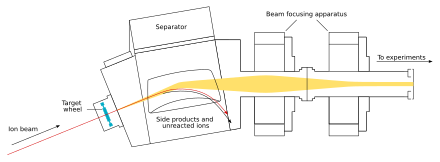

[1][57] From April to September 2012, an attempt to synthesize 295Uue and 296Uue was made by bombarding a target of berkelium-249 with titanium-50 at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Darmstadt, Germany.

[55] Due to the predicted short half-lives, the GSI team used new "fast" electronics capable of registering decay events within microseconds.

[60][55] The experiment was originally planned to continue to November 2012,[61] but was stopped early to make use of the 249Bk target to confirm the synthesis of tennessine (thus changing the projectile to 48Ca).

[60] The team at RIKEN in Wakō, Japan began bombarding curium-248 targets with a vanadium-51 beam in January 2018[62] to search for element 119.

The report recommended that if the 5 fb cross-section limit is reached without any events observed, then the team should "evaluate and eventually reconsider the experimental strategy before taking additional beam time.

[69] The team at the JINR plans to attempt synthesis of element 119 in the future, but a precise timeframe has not been publicly released.

[72] The team at the Heavy Ion Research Facility in Lanzhou (HIRFL), which is operated by the Institute of Modern Physics (IMP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, also plans to try the 243Am+54Cr reaction.

Using the 1979 IUPAC recommendations, the element should be temporarily called ununennium (symbol Uue) until it is discovered, the discovery is confirmed, and a permanent name chosen.

This concept, proposed by University of California professor Glenn Seaborg, explains why superheavy elements last longer than predicted.

[1] The main reason for the predicted differences between ununennium and the other alkali metals is the spin–orbit (SO) interaction—the mutual interaction between the electrons' motion and spin.

Computational chemists understand the split as a change of the second (azimuthal) quantum number ℓ from 1 to 1⁄2 and 3⁄2 for the more-stabilized and less-stabilized parts of the 7p subshell, respectively.

[1] This stabilization of the outermost s-orbital (already significant in francium) is the key factor affecting ununennium's chemistry, and causes all the trends for atomic and molecular properties of alkali metals to reverse direction after caesium.

[86] Indeed, the static dipole polarisability (αD) of ununennium, a quantity for which the impacts of relativity are proportional to the square of the element's atomic number, has been calculated to be small and similar to that of sodium.

[2][3][88] The chemistry of ununennium is predicted to be similar to that of the alkali metals,[1] but it would probably behave more like potassium[90] or rubidium[1] than caesium or francium.

This is due to relativistic effects, as in their absence periodic trends would predict ununennium to be even more reactive than caesium and francium.

The metal–metal bond lengths in these M2 molecules increase down the group from Li2 to Cs2, but then decrease after that to Uue2, due to the aforementioned relativistic effects that stabilize the 8s orbital.

[5] The UueF molecule is expected to have a significant covalent character owing to the high electron affinity of ununennium.

This is very different from the behaviour of s-block elements, as well as gold and mercury, in which the s-orbitals (sometimes mixed with d-orbitals) are the ones participating in the bonding.

[86] The ΔHsub and −ΔHads values for the alkali metals change in opposite directions as atomic number increases.