Urban renewal

These efforts frequently aim to transform underutilized urban areas into hubs of economic and cultural activity, leveraging policies that promote both sustainability and equitable development.

For example, green infrastructure projects, such as urban parks and community gardens, not only enhance property values but also foster social cohesion and provide environmental benefits like improved water management and biodiversity conservation.

These stakeholders often collaborate with governments and private entities to redevelop vacant land into dynamic public spaces, such as pop-up cultural venues or urban beaches.

Culturepreneur initiatives are designed to bridge the gap between the needs of urban residents, local authorities, and property developers, fostering innovative, community-driven solutions.

Addressing these challenges requires a deliberate focus on equitable development strategies, as demonstrated by initiatives like the ReGenesis Project in South Carolina, which combines environmental cleanup with community-driven planning.

A primary purpose of urban renewal is to restore economic viability to a given area by attracting external private and public investment and by encouraging business start-ups and survival.

Poorly-conceived designs can lead to the destruction of functional neighborhoods and the creation of new ones which are less desirable or replaced with experimental new development patterns which prove undesirable or not economically sustainable.

Displacement may be a stated or covert intention of the project, but it may also happen when other renewal objectives are prioritized over the ability of residents to stay in their area, or as an unforeseen consequence of planning decisions.

Indirect displacement can also result from the interplay of renewal projects and social inequalities, for example when people face discrimination in the housing market based on racial identity.

In 2016, Portland Development Commission apologised again after the funds instead went into multimillion-dollar apartment projects, the increasing prices force the African-American and other low-income residents out of the market.

Professor Kenneth Paul Tan writes that Singapore's self-image of having succeeded against all odds has led to strong pressure to pursue progress and development regardless of the destructive cost, postulating that Singapore's "culture of comfort and affluence" has developed in order to cope with people's repeated loss of their sense of place, redirecting their desires from "community" towards "economic progress, upward mobility, affluent and convenient lifestyles and a ‘world-class’ city.

[20] The CBDs and inner suburban areas of Australia's cities have been in constant renewal since the 19th century, however apart from large commercial re-developments this has mostly been done in ad-hoc fashion rather than as major planning initiative.

In Rio de Janeiro, the Porto Maravilha [pt] is a large-scale urban waterfront revitalization project, which covers a centrally located five million square meter area.

In terms of the similarity sharing with U.S. urban renewal programs, both countries viewed older neighborhoods as outdated and blighted, encouraged local governments to cooperate with local development interests for downtown redevelopment, failed to provide enough support and concern for residents of cleared areas, who often were the low-income residents, and building plenty of highways to reach large scale urban sprawl.

People remain living inside the buildings during the renovation period, which usually lasts for over a year, leading to concerns about exposure to construction dust and the possible presence of asbestos.

Examples most often cited as successes include Temple Bar in Dublin where tourism was attracted to a bohemian 'cultural quarter', Israel has been undergoing extensive urban renewal projects due to the large number of concrete tenement buildings in its cities which do not meet modern Israeli safety standards and have what is widely considered to be an impoverished and unattractive appearance.

This law defines the urban regeneration as "the coordinated set of urban-building interventions and social initiatives that can include replacement, re-use, redevelopment of the built environment and reorganization of the urban landscape by mean of recovery of degraded, underused or abandoned areas, as well as through the creation and management of infrastructure, green spaces and services […] with a horizon towards sustainability and environmental and social resilience, technological innovation and increasing biodiversity" (Art 2.

Its historical development began in 1976, when the Taipei Municipal Government accepted the proposal to redevelop the area east of the Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hall.

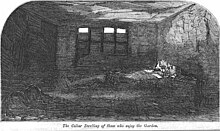

The Housing Act of 1930 gave local councils wide-ranging powers to demolish properties unfit for human habitation or that posed a danger to health, and obligated them to rehouse those people who were relocated due to the large scale slum clearance programs.

In an effort to rehouse the poorest people affected by redevelopment, the rent for housing was set at an artificially low level, although this policy also only achieved mixed success.

This approach supports important themes in urban renewal today, such as participation, sustainability and trust – and government acting as advocate and 'enabler', rather than an instrument of command and control.

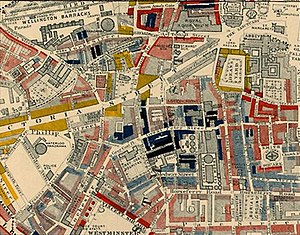

[54] Prior to the Urban Renewal policies of the 1950s, cities in the United States revitalized with large scale projects like the design and construction of Central Park in New York and the 1909 Plan for Chicago by Daniel Burnham.

[55] In 1944, the GI Bill (officially the Serviceman's Readjustment Act) guaranteed Veterans Administration (VA) mortgages to veterans under favorable terms, which fueled suburbanization after the end of World War II, as places like Levittown, New York, Warren, Michigan and the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles were transformed from farmland into cities occupied by tens of thousands of families in a few years.

A large section of downtown at the heart of the city was demolished, converted to parks, office buildings, and a sports arena and renamed the Golden Triangle in what was generally recognized as a major success.

[59] Because of the ways in which it targeted the most disadvantaged sector of the American population, novelist James Baldwin famously dubbed Urban Renewal "Negro Removal" in the 1960s.

This resulted in a serious degradation of the tax bases of many cities, isolated entire neighborhoods,[62] and meant that existing commercial districts were bypassed by the majority of commuters.

The Rondout neighborhood in Kingston, New York (on the Hudson River) was essentially destroyed by a federally funded urban renewal program in the 1960s, with more than 400 old buildings demolished, most of them historic brick structures built in the 19th century.

In San Francisco, Joseph Alioto was the first mayor to publicly repudiate the policy of urban renewal, and with the backing of community groups, forced the state to end construction of highways through the heart of the city.

The Rainbow Centre interrupted the street grid, taking up three blocks, and parking ramps isolated the city from the core, leading to the degradation of nearby neighborhoods.

[68] In post-apartheid South Africa major grassroots social movements such as the Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign and Abahlali baseMjondolo emerged to contest 'urban renewal' programs that forcibly relocated the poor out of the cities.