Urdu alphabet

There are efforts under way to develop more sophisticated and user-friendly Urdu support on computers and the internet.

The Nastaliq calligraphic writing style began as a Persian mixture of the Naskh and Ta'liq scripts.

After the Muslim conquest of the Indian subcontinent, Nastaʻliq became the preferred writing style for Urdu.

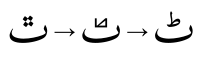

But the Nastaliq style in which Urdu is written uses more than three general forms for many letters, even in simple non-decorative documents.

Tāʼ marbūṭah is also sometimes considered the 40th letter of the Urdu alphabet, though it is rarely used except for in certain loan words from Arabic.

Hamza can be difficult to recognise in Urdu handwriting and fonts designed to replicate it, closely resembling two dots above as featured in ت Té and ق Qaf, whereas in Arabic and Geometric fonts it is more distinct and closely resembles the western form of the numeral 2 (two).

Like in its parent Arabic alphabet, Urdu vowels are represented using a combination of digraphs and diacritics.

Short vowels (a, i, u) are represented by optional diacritics (zabar, zer, pesh) upon the preceding consonant or a placeholder consonant (alif, ain, or hamzah) if the syllable begins with the vowel, and long vowels by consonants alif, ain, ye, and wa'o as matres lectionis, with disambiguating diacritics, some of which are optional (zabar, zer, pesh), whereas some are not (madd, hamzah).

At the beginning of a word, alif can be used to represent any of the short vowels: اب ab, اسم ism, اردو Urdū.

For long ā at the beginning of words alif-mad is used: آپ āp, but a plain alif in the middle and at the end: بھاگنا bhāgnā.

Only when preceded by the consonant k͟hē (خ), can wāʾo render the "u" ([ʊ]) sound (such as in خود, "k͟hud" - myself), or not pronounced at all (such as in خواب, "k͟haab" - dream).

Ayn in its initial and final position is silent in pronunciation and is replaced by the sound of its preceding or succeeding vowel.

If the first word ends in choṭī he (ہ) or ye (ی or ے) then hamzā (ء) is used above the last letter (ۂ or ئ or ۓ).

[21] Other early code pages which represented Urdu alphabets were Windows-1256 and MacArabic encoding both of which date back to the mid-1990s.

In Pakistan, the 8-bit code page which is developed by National Language Authority is called Urdu Zabta Takhti (اردو ضابطہ تختی) (UZT)[22] which represents Urdu in its most complete form including some of its specialized diacritics, though UZT is not designed to coexist with the Latin alphabet.

For example, the University of Chicago's electronic copy of John Shakespear's "A Dictionary, Hindustani, and English"[24] includes the word 'بهارت' (bhārat "India").

In Urdu, the /h/ phoneme is represented by the character U+06C1, called gol he (round he), or chhoti he (small he).

In 2003, the Center for Research in Urdu Language Processing (CRULP)[26]—a research organisation affiliated with Pakistan's National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences—produced a proposal for mapping from the 1-byte UZT encoding of Urdu characters to the Unicode standard.

There are efforts underway to develop more sophisticated and user-friendly Urdu support on computers and on the Internet.

[29] Apple implemented the Urdu language keyboard across Mobile devices in its iOS 8 update in September 2014.

[31] The National Language Authority of Pakistan has developed a number of systems with specific notations to signify non-English sounds, but these can only be properly read by someone already familiar with the loan letters.

[citation needed] Roman Urdu also holds significance among the Christians of Pakistan and North India.