Hiroshige

The subjects of his work were atypical of the ukiyo-e genre, whose typical focus was on beautiful women, popular actors, and other scenes of the urban pleasure districts of Japan's Edo period (1603–1868).

For scholars and collectors, Hiroshige's death marked the beginning of a rapid decline in the ukiyo-e genre, especially in the face of the westernization that followed the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

[3] He was of a samurai background,[3] and is the great-grandson of Tanaka Tokuemon, who held a position of power under the Tsugaru clan in the northern province of Mutsu.

Hiroshige's father, Gen'emon, was adopted into the family of Andō Jūemon, whom he succeeded as fire warden for the Yayosu Quay area.

[10] About 1831, his Ten Famous Places in the Eastern Capital appeared, and seem to bear the influence of Hokusai, whose popular landscape series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji had recently seen publication.

[13] An invitation to join an official procession to Kyoto in 1832 gave Hiroshige the opportunity to travel along the Tōkaidō route that linked the two capitals.

As he had never been west of Kyoto, Hiroshige-based his illustrations of Naniwa (modern Osaka) and Ōmi Province on pictures found in books and paintings.

[14] Hiroshige's first wife helped finance his trips to sketch travel locations, in one instance selling some of her clothing and ornamental combs.

She died in October 1838, and Hiroshige remarried to Oyasu,[b] sixteen years his junior, daughter of a farmer named Kaemon from Tōtōmi Province.

[19] In One Hundred Famous Views of Edo Hiroshige frequently places large-scale objects, people and animals, or parts of them, in the foreground.

In his declining years, Hiroshige still produced thousands of prints to meet the demand for his works, but few were as good as those of his early and middle periods.

In no small part, his prolific output stemmed from the fact that he was poorly paid per series, although he was still capable of remarkable art when the conditions were right — his great One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (名所江戸百景 Meisho Edo Hyakkei) was paid for up-front by a wealthy Buddhist priest in love with the daughter of the publisher, Uoya Eikichi (a former fishmonger).

[22] He largely confined himself in his early work to common ukiyo-e themes such as women (美人画 bijin-ga) and actors (役者絵 yakusha-e).

Then, after the death of Toyohiro, Hiroshige made a dramatic turnabout, with the 1831 landscape series Famous Views of the Eastern Capital (東都名所 Tōto Meisho) which was critically acclaimed for its composition and colors.

Increasingly large series were produced to meet demand, and this trend can be seen in Hiroshige's work, such as The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

Hiroshige's The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1833–1834) and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856–1858) greatly influenced French Impressionists such as Monet.

Hiroshige's style also influenced the Mir iskusstva, a 20th-century Russian art movement in which Ivan Bilibin and Mstislav Dobuzhinsky were major artists.

[25] Hiroshige was regarded by Louise Gonse, director of the influential Gazette des Beaux-Arts and author of the two volume L'Art Japonais in 1883, as the greatest painter of landscapes of the 19th century.

Returning Sails at Tsukuda , from Eight Views of Edo , early-19th century

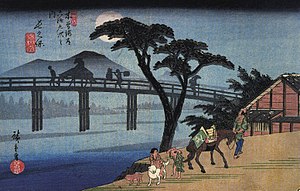

Oiwake , from The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō , 1830s