Utilitarianism

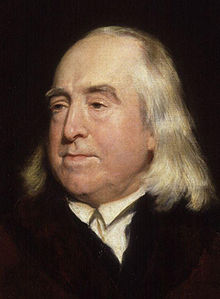

For instance, Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, described utility as the capacity of actions or objects to produce benefits, such as pleasure, happiness, and good, or to prevent harm, such as pain and unhappiness, to those affected.

The tradition of modern utilitarianism began with Jeremy Bentham, and continued with such philosophers as John Stuart Mill, Henry Sidgwick, R. M. Hare, and Peter Singer.

The concept has been applied towards social welfare economics, questions of justice, the crisis of global poverty, the ethics of raising animals for food, and the importance of avoiding existential risks to humanity.

Consequentialist theories were first developed by the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi, who proposed a system that sought to maximize benefit and eliminate harm.

[5] Mohist consequentialism advocated communitarian moral goods, including political stability, population growth, and wealth, but did not support the utilitarian notion of maximizing individual happiness.

Utilitarianism as a distinct ethical position only emerged in the 18th century, and although it is usually thought to have begun with Jeremy Bentham, there were earlier writers who presented theories that were strikingly similar.

If any false opinion, embraced from appearances, has been found to prevail; as soon as farther experience and sounder reasoning have given us juster notions of human affairs, we retract our first sentiment, and adjust anew the boundaries of moral good and evil.Gay's theological utilitarianism was developed and popularized by William Paley.

It has been claimed that Paley was not a very original thinker and that the philosophies in his treatise on ethics is "an assemblage of ideas developed by others and is presented to be learned by students rather than debated by colleagues.

"[18] Nevertheless, his book The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy (1785) was a required text at Cambridge[18] and Smith (1954) says that Paley's writings were "once as well known in American colleges as were the readers and spellers of William McGuffey and Noah Webster in the elementary schools.

Apart from restating that happiness as an end is grounded in the nature of God, Paley also discusses the place of rules, writing:[21] [A]ctions are to be estimated by their tendency.

Perhaps aware that Francis Hutcheson eventually removed his algorithms for calculating the greatest happiness because they "appear'd useless, and were disagreeable to some readers,"[24] Bentham contends that there is nothing novel or unwarranted about his method, for "in all this there is nothing but what the practice of mankind, wheresoever they have a clear view of their own interest, is perfectly conformable to."

Whereas, intellectual pursuits give long-term happiness because they provide the individual with constant opportunities throughout the years to improve his life, by benefiting from accruing knowledge.

Hall (1949) and Popkin (1950) defend Mill against this accusation pointing out that he begins Chapter Four by asserting that "questions of ultimate ends do not admit of proof, in the ordinary acceptation of the term" and that this is "common to all first principles".

[43] He identifies three methods: intuitionism, which involves various independently valid moral principles to determine what ought to be done, and two forms of hedonism, in which rightness only depends on the pleasure and pain following from the action.

But, for the most part, the consideration of what would happen if everyone did the same, is the only means we have of discovering the tendency of the act in the particular case.Some school level textbooks and at least one British examination board make a further distinction between strong and weak rule utilitarianism.

Another response might be that the riots the sheriff is trying to avoid might have positive utility in the long run by drawing attention to questions of race and resources to help address tensions between the communities.

An older form of this argument was presented by Fyodor Dostoyevsky in his book The Brothers Karamazov, in which Ivan challenges his brother Alyosha to answer his question:[84] Tell me straight out, I call on you—answer me: imagine that you yourself are building the edifice of human destiny with the object of making people happy in the finale, of giving them peace and rest at last, but for that you must inevitably and unavoidably torture just one tiny creature, [one child], and raise your edifice on the foundation of her unrequited tears—would you agree to be the architect on such conditions? ...

"[99] Robert Goodin takes yet another approach and argues that the demandingness objection can be "blunted" by treating utilitarianism as a guide to public policy rather than one of individual morality.

[103] The concept is also important in animal rights advocate Richard Ryder's rejection of utilitarianism, in which he talks of the "boundary of the individual", through which neither pain nor pleasure may pass.

"[106] Thus, the aggregation of utility becomes futile as both pain and happiness are intrinsic to and inseparable from the consciousness in which they are felt, rendering impossible the task of adding up the various pleasures of multiple individuals.

Can anyone who really considers the matter seriously honestly claim to believe that it is worse that one person die than that the entire sentient population of the universe be severely mutilated?

Lord Devlin notes, 'if the reasonable man "worked to rule" by perusing to the point of comprehension every form he was handed, the commercial and administrative life of the country would creep to a standstill.

Thomas Carlyle derided "Benthamee Utility, virtue by Profit and Loss; reducing this God's-world to a dead brute Steam-engine, the infinite celestial Soul of Man to a kind of Hay-balance for weighing hay and thistles on, pleasures and pains on".

With such rubbish has the brave fellow, with his motto, "nulla dies sine linea [no day without a line]", piled up mountains of books.Pope John Paul II, following his personalist philosophy, argued that a danger of utilitarianism is that it tends to make persons, just as much as things, the object of use.

Consequently, "the decay of population is the greatest evil that a state can suffer; and the improvement of it the object which ought, in all countries, to be aimed at in preference to every other political purpose whatsoever.

According to Derek Parfit, using total happiness falls victim to the repugnant conclusion, whereby large numbers of people with very low but non-negative utility values can be seen as a better goal than a population of a less extreme size living in comfort.

The former view is the one adopted by Bentham and Mill, and (I believe) by the Utilitarian school generally: and is obviously most in accordance with the universality that is characteristic of their principle ... it seems arbitrary and unreasonable to exclude from the end, as so conceived, any pleasure of any sentient being.

Nick Bostrom and Carl Shulman consider that, as advancements in artificial intelligence continue, it will probably be possible to engineer digital minds that require less resources and have a much higher rate and intensity of subjective experience than humans.

[147] The concept has been applied towards social welfare economics, questions of justice, the crisis of global poverty, the ethics of raising animals for food, and the importance of avoiding existential risks to humanity.

[150] Many utilitarian philosophers, including Peter Singer and Toby Ord, argue that inhabitants of developed countries in particular have an obligation to help to end extreme poverty across the world, for example by regularly donating some of their income to charity.