Utopia (book)

It is variously rendered as any of the following: The first created original name was even longer: Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia.

The letters also explain the lack of widespread travel to Utopia; during the first mention of the land, someone had coughed during announcement of the exact longitude and latitude.

The first book tells of the traveller Raphael Hythlodaeus, to whom More is introduced in Antwerp, and it also explores the subject of how best to counsel a prince, a popular topic at the time.

He, however, points out: Plato doubtless did well foresee, unless kings themselves would apply their minds to the study of philosophy, that else they would never thoroughly allow the council of philosophers, being themselves before, even from their tender age, infected and corrupt with perverse and evil opinions.More seems to contemplate the duty of philosophers to work around and in real situations and, for the sake of political expediency, work within flawed systems to make them better, rather than hoping to start again from first principles.

... for in courts they will not bear with a man's holding his peace or conniving at what others do: a man must barefacedly approve of the worst counsels and consent to the blackest designs, so that he would pass for a spy, or, possibly, for a traitor, that did but coldly approve of such wicked practices.Utopia is placed in the New World and More links Raphael's travels with Amerigo Vespucci's real life voyages of discovery.

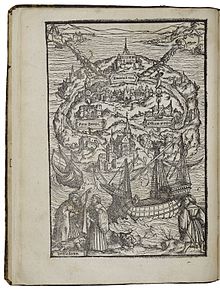

These ends, curved round as if completing a circle five hundred miles in circumference, make the island crescent-shaped, like a new moon.

[10]The island was originally a peninsula but a 15-mile wide channel was dug by the community's founder King Utopos to separate it from the mainland.

There is deliberate simplicity about the trades; for instance, all people wear the same types of simple clothes, and there are no dressmakers making fine apparel.

More does allow scholars in his society to become the ruling officials or priests, people picked during their primary education for their ability to learn.

The gold is part of the community wealth of the country, and fettering criminals with it or using it for shameful things like chamber pots gives the citizens a healthy dislike of it.

Privacy is not regarded as freedom in Utopia; taverns, ale houses and places for private gatherings are nonexistent for the effect of keeping all men in full view and so they are obliged to behave well.

In an amicable dialogue with More and Giles, Hythloday expresses strong criticism of then-modern practices in England and other Catholicism-dominated countries, such as the crime of theft being punishable by death, and the over-willingness of kings to start wars (Getty, 321).

Book two has Hythloday tell his interlocutors about Utopia, where he has lived for five years, with the aim of convincing them about its superior state of affairs.

[14] He has argued that More was taking part in the Renaissance humanist debate over true nobility, and that he was writing to prove the perfect commonwealth could not occur with private property.

Quentin Skinner's interpretation of Utopia is consistent with the speculation that Stephen Greenblatt made in The Swerve: How the World Became Modern.

There, Greenblatt argued that More was under the Epicurean influence of Lucretius's On the Nature of Things and the people that live in Utopia were an example of how pleasure has become their guiding principle of life.

The suggestion that More may have agreed with the views of Raphael is given weight by the way he dressed; with "his cloak... hanging carelessly about him", a style that Roger Ascham reports that More himself was wont to adopt.

[19] According to Burlinson, More interprets that decadent expression of animal cruelty as a causal antecedent for the cruel intercourse present within the world of Utopia and More's own.

[19] Burlinson does not argue that More explicitly equates animal and human subjectivities, but is interested in More's treatment of human-animal relations as significant ethical concerns intertwined with religious ideas of salvation and the divine qualities of souls.

For example, indigenous Americans, although referred to as "noble savages" in many circles, showed the possibility of living in social harmony [with nature] and prosperity without the rule a king...".

The early British and French settlers in the 1500 and 1600s were relatively shocked to see how the native Americans moved around so freely across the untamed land, not beholden by debt, "lack of magistrates, forced services, riches, poverty or inheritance".

[21] In Utopian Justifications: More’s Utopia, Settler Colonialism, and Contemporary Ecocritical Concerns, Susan Bruce juxtaposes Utopian justifications for the violent dispossession of idle peoples unwilling to surrender lands that are underutilized with Peter Kosminsky's The Promise, a 2011 television drama centered around Zionist settler colonialism in modern-day Palestine.

[22] Bruce's treatment of Utopian foreign policy, which mirrored European concerns in More's day, situates More's text as an articulation of settler colonialism.

[22] Bruce identifies an isomorphic relationship between Utopian settler logic and the account provided by The Promise’s Paul, who recalls his father's criticism of Palestinians as undeserving, indolent, and animalistic occupants of the land.

More started by writing the introduction and the description of the society that would become the second half of the work, and on his return to England, he wrote the "dialogue of counsel".

The word 'utopia', invented by More as the name of his fictional island and used as the title of his book, has since entered the English language to describe any imagined place or state of things in which everything is perfect.

The antonym 'dystopia' is used for hypothetical places of great suffering or injustice, including systems that present or market themselves as utopian but actually have terrible other sides to them.

Although he may not have directly founded the contemporary notion of what has since become known as Utopian and dystopian fiction, More certainly popularised the idea of imagined parallel realities, and some of the early works that owe a debt to Utopia must include The City of the Sun by Tommaso Campanella, Description of the Republic of Christianopolis by Johannes Valentinus Andreae, New Atlantis by Francis Bacon and Candide by Voltaire.

[citation needed] An applied example of More's Utopia can be seen in Vasco de Quiroga's implemented society in Michoacán, Mexico, which was directly inspired by More's work.