Van Ness Bus Rapid Transit

It was built as part of the $346 million Van Ness Improvement Project, which also included utility replacement and pedestrian safety features.

The red concrete was then poured, with dowel baskets to join adjacent slabs, then topped with a color hardener layer.

The finished lane pavement has a compressive strength of 8,000 pounds per square inch (55,000 kPa), 60% stronger than a typical roadway, extending its life.

SFMTA normally operates two primary routes along the full length of the BRT corridor – 47 Van Ness and 49 Van Ness-Mission – with combined headways as low as 3.5 minutes; several other routes (including the 30X Stockton Express, 76X Marin Headlands, 79X Arena Express, and 90 San Bruno Owl) operate on part or all of the corridor at lower frequencies.

[7]: 13, 32 GGT buses use only the seven stops from Union to Eddy, as they run on Golden Gate Avenue and McAllister Street to reach downtown San Francisco.

[14] A 2021 civil grand jury report determined the planning process had failed to account for the location and future maintenance of underground utility lines; because existing water and sewer lines were buried under the center of Van Ness, they had to be relocated curbside to avoid future disruption of BRT service when these utilities required maintenance.

[12]: 7–9 Although the general position of the existing utility lines was known as early as 2006, detailed survey maps and routing were not developed until after the project had started construction, and the task of determining exact utility routing fell on the construction contractor rather than SFMTA, exceeding the contractor's intended scope of responsibilities and causing project cost and schedule overruns.

[12]: 10–11 In August 2013, a selection panel of the San Francisco Arts Commission (SFAC) recommended the proposal from Cuban-born artist Jorge Pardo for consideration by the full SFAC over competing proposals from Norie Sato and Janet Zweig for a series of three sculptures that would be installed at the Market, Sutter and Union stations.

[24] Businesses along Van Ness complained of lost customers due to construction disruption and the delays in completion.

[26][27] Field tests indicated that interference with wheel lug nuts would create a gap at least 5 in (130 mm) wide between the edge of a 14-inch-high platform and the boarding doors, and bridge plates would be required at middle doors to meet ADA standards for level boarding; the added complexity could impact vehicle reliability.

In addition, because the buses would also operate outside the Van Ness BRT corridor, they would continue to need to be equipped with boarding ramps at the front door for regular curbside service.

[28] The original concrete poles built to support the overhead electrical supply lines for the streetcars in 1914 were moved onto the sidewalks in 1936 to accommodate the widening of Van Ness.

[29]: 1–2 Since then, the poles have deteriorated due to extra loads from additional wires (added for the electrical return path when the lines were converted to trolleybus service) and modified catenary geometry, exhibiting significant spalling and cracking.

[29]: 1–3 A 2009 evaluation of the original 1914/36 poles concluded they could not be rehabilitated and retrofitted for use on the modern BRT line because of their shape, height, and inadequate foundation.

[29]: 1–4 [23] A separate report determined the original trolley poles were not eligible for retention on a historical basis due to their loss of physical integrity.

[30]: 60 The city's Historic Preservation Commission provided conditional approval to remove the original 1914/1936 trolley poles and streetlamps in November 2015, but preservationists were concerned over the loss of the Van Ness "Ribbon of Light" and three prominent organizations formed the "Coalition to Save the Historic Streetlamps of Van Ness Avenue" in 2016.

[23][31] The Board of Supervisors unanimously passed a resolution on September 20, 2016, urging SFMTA to "make all efforts to preserve the historic character of the Van Ness Corridor".

[33] As a compromise, four poles were retained and restored in front of San Francisco City Hall and War Memorial Plaza.

[36] Van Ness, famed as the widest street in the city and for its row of auto dealerships, also became busy with automobile traffic, as it became part of U.S. Route 101 in 1926.

[30]: 23, 31 In 1934, with the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge imminent, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors proposed to expand surface streets to facilitate automobile traffic, including widening Van Ness from Market to Bay.

[42] The Proposition B sales tax expenditure plan, approved in 1989, included funding for "transit service improvements on Van Ness Avenue".

[46][47]: 67, 113 Collectively, the Geary and Van Ness corridors had more than 200,000 automobile-based person-trips per day, with BRT implementation anticipated to remove approximately 4,500 vehicles at peak periods.

[5] The proposed projects on Van Ness and Geary were anticipated to have short construction times (between 18 and 24 months) and lower costs than rail lines.

[53] The "lengthy planning, review, and public-participation process" in 2014 was faulted for causing delays in BRT implementation, as opposition to the removal of an automobile lane and impacts to parking were not offset by a local working example demonstrating its benefits.

[56] The first phase of construction involved the removal and replacement of underground water and sewer lines, some of which dated back to the 19th century.

[64] Items uncovered during utility work covered a broad range of history, from Ohlone artefacts to abandoned fiber optic cables originally placed during the dot-com boom.

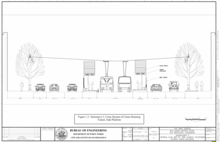

[73] The first red concrete was poured for the BRT lanes on November 10, 2020, and hundreds of trees were planted along Van Ness at approximately the same time.

Species planted include lemon-scented gum along the median and London plane, Brisbane box, and palm trees along the sidewalk.