John Vanbrugh

In his career as a playwright, he offended many sections of Restoration and 18th century society, not only by the sexual explicitness of his plays, but also by their messages in defence of women's rights in marriage.

Downes' example of one sugar baker's house in Liverpool, estimated to bring in £40,000 a year in trade from Barbados, throws a new light on Vanbrugh's social background, one rather different from the picture of a backstreet Chester sweetshop as painted by Leigh Hunt in 1840 and reflected in many later accounts.

[citation needed] Taken in this context, though he has sometimes been viewed as an odd or unqualified appointee to the College of Arms, it is not surprising, given the social expectations of his day, that by descent his credentials for his offices there were sound.

His forebears, both Flemish/Dutch and English, were armigerous, and their coats of arms can be traced in three out of four cases, revealing that Vanbrugh was of gentle descent (Jacobson, of Antwerp and London [the family of his paternal grandmother Maria daughter of Peter brother to Philip Jacobson, jeweller and financier to successive English kings, James I, and Charles I, and monied backer of the Second Virginia Company and the East India Company]; Carleton of Imber Court; Croft of Croft Castle).

[citation needed] After growing up in a large household in Chester (12 children of his mother's second marriage survived infancy), the question of how Vanbrugh spent the years from age 18 to 22 (after he left school) was long unanswered, with the baseless suggestion sometimes made that he had been studying architecture in France (stated as fact in the Dictionary of National Biography).

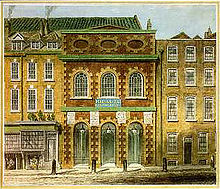

[10] In spite of the distant noble relatives and the lucrative sugar trade, Vanbrugh never seemed to possess any capital for business ventures (such as the Haymarket Theatre), but always had to rely on loans and backers.

The often-repeated claim that Vanbrugh wrote part of his comedy The Provoked Wife in the Bastille is based on allusions in a couple of much later memoirs and is regarded with some doubt by modern scholars (see McCormick).

[21] After being released from the Bastille, he had to spend three months in Paris, free to move around but unable to leave the country, and with every opportunity to see an architecture "unparalleled in England for scale, ostentation, richness, taste and sophistication".

[24] The Club is best known today as an early 18th-century social gathering point for culturally and politically prominent Whigs, including many artists and writers (William Congreve, Joseph Addison, Godfrey Kneller) and politicians (the Duke of Marlborough, Charles Seymour, the Earl of Burlington, Thomas Pelham-Holles, Sir Robert Walpole and Richard Temple, 1st Viscount Cobham who gave Vanbrugh several architectural commissions at Stowe).

Politically, the Club promoted the Whig objectives of a strong Parliament, a limited monarchy, resistance to France,[citation needed] and primarily the Protestant succession to the throne.

Theatre was under threat from more colourful types of entertainment such as opera, juggling, pantomime (introduced by John Rich), animal acts, travelling dance troupes, and famous visiting Italian singers.

A new comedy staged with the makeshift remainder of the company in January 1696, Colley Cibber's Love's Last Shift, had a final scene that to Vanbrugh's critical mind demanded a sequel, and even though it was his first play he threw himself into the fray by providing it.

Love's Last Shift has not been staged again since the early 18th century and is read only by the most dedicated scholars, who sometimes express distaste for its businesslike combination of four explicit acts of sex and rakishness with one of sententious reform (see Hume[page needed]).

[34] That new play, The Relapse, did turn out a tremendous success that saved the company, not least by virtue of Colley Cibber again bringing down the house with his second impersonation of Lord Foppington.

While The Relapse had been robustly phrased to be suitable for amateurs and minor acting talents, he could count on versatile professionals like Thomas Betterton, Elizabeth Barry, and the rising young star Anne Bracegirdle to do justice to characters of depth and nuance.

In 1698, Vanbrugh's argumentative and sexually frank plays were singled out for special attention by Jeremy Collier in his Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage, particularly for their failure to impose exemplary morality by appropriate rewards and punishments in the fifth act.

On his release from prison (he was at the Bastille by then) on 22 November 1692 he spent a short time in Paris,[37] there he would have seen much recent architecture including Les Invalides, the Collège des Quatre-Nations and the east wing of the Louvre Palace.

In the contest for the commission of Castle Howard, the untrained and untried Vanbrugh astonishingly managed to out-charm and out-clubman the professional but less socially adept Talman and to persuade the Earl of Carlisle to give the great opportunity to him instead.

Castle Howard, with its immense corridors in segmental colonnades leading from the main entrance block to the flanking wings, its centre crowned by a great domed tower complete with cupola, is very much in the school of classic European baroque.

[51] The gate, its tapering walls creating an illusion of greater height, also serves as water tower for the palace, thus confounding those of Vanbrugh's critics, such as the Duchess, who accused him of impracticability.

[51] Blenheim, the largest non-royal domestic building in England, consists of three blocks, the centre containing the living and state rooms, and two flanking rectangular wings both built around a central courtyard: one contains the stables, and the other the kitchens, laundries, and storehouses.

Over the south portico (illustrated right), itself a massive and dense construction of piers and columns, definitely not designed in the Palladian manner for elegant protection from the sun, a huge bust of Louis XIV is forced to look down on the splendours and rewards of his conqueror.

Perhaps to improve the view down to Avonmouth, the centre was remodelled by Mylne with a canted bay window, at odds with the tautness of Vanbrugh's overall design of the house, in which all planes were parallel or perpendicular to the walls.

Already discouraged and upset by the reception the palace was receiving from the Whig factions, the final blow for Vanbrugh came when the Duke was incapacitated in 1717 by a severe stroke, and the thrifty (and hostile) Duchess took control.

The craftsmen brought in by the Duchess, under the guidance of furniture designer James Moore, completed the work in perfect imitation of the greater masters, so perhaps there was fault and intransigence on both sides in this famed argument.

[58] That Vanbrugh's work at Blenheim has been the subject of criticism can largely be blamed on those, including the Duchess, who failed to understand the chief reason for its construction: to celebrate a martial triumph.

Voltaire, who visited Blenheim Palace in the autumn of 1727, described it as 'a great mass of stone with neither charm nor taste' and thought that if the apartments 'were but as spacious as the walls thick, the house would be commodious enough'.

But if we consider that Sir John Vanbrugh was to construct a building of endless duration, that no bounds were set to expense, and that an edifice was required that should strike with awe and surprise even at a distance; the architect may be excused for having sacrificed, in some degree, the elegance of design to multiplicity of ornament.

So true it is, that genius is not confined to one subject, but wherever exercised, is equally manifest.In 1766 Lord Stanhope described the Roman amphitheatre at Nîmes as 'Ugly and clumsy enough to have been the work of Vanbrugh if it had been in England.

'[66] In his fifth Royal Academy lecture of 1810, Sir John Soane said that 'By studying his works the artist will acquire a bold flight of irregular fancy',[67] calling him 'the Shakespeare of architects'.