Variable star

[2] An ancient Egyptian calendar of lucky and unlucky days composed some 3,200 years ago may be the oldest preserved historical document of the discovery of a variable star, the eclipsing binary Algol.

[3][4][5] Aboriginal Australians are also known to have observed the variability of Betelgeuse and Antares, incorporating these brightness changes into narratives that are passed down through oral tradition.

This discovery, combined with supernovae observed in 1572 and 1604, proved that the starry sky was not eternally invariable as Aristotle and other ancient philosophers had taught.

[10] Her analyses and observations of variable stars, carried out with her husband, Sergei Gaposchkin, laid the basis for all subsequent work on the subject.

By combining light curve data with observed spectral changes, astronomers are often able to explain why a particular star is variable.

[13] For example, evidence for a pulsating star is found in its shifting spectrum because its surface periodically moves toward and away from us, with the same frequency as its changing brightness.

Classical Cepheids (or Delta Cephei variables) are population I (young, massive, and luminous) yellow supergiants which undergo pulsations with very regular periods on the order of days to months.

Type II Cepheids (historically termed W Virginis stars) have extremely regular light pulsations and a luminosity relation much like the δ Cephei variables, so initially they were confused with the latter category.

These stars of spectral type A or occasionally F0, a sub-class of δ Scuti variables found on the main sequence.

Alpha Cygni (α Cyg) variables are nonradially pulsating supergiants of spectral classes Bep to AepIa.

Gamma Doradus (γ Dor) variables are non-radially pulsating main-sequence stars of spectral classes F to late A.

Variability of more massive (2–8 solar mass) Herbig Ae/Be stars is thought to be due to gas-dust clumps, orbiting in the circumstellar disks.

Variability of T Tauri stars is due to spots on the stellar surface and gas-dust clumps, orbiting in the circumstellar disks.

These stars reside in reflection nebulae and show gradual increases in their luminosity in the order of 6 magnitudes followed by a lengthy phase of constant brightness.

FU Orionis variables are of spectral type A through G and are possibly an evolutionary phase in the life of T Tauri stars.

Giant eruptions observed in a few LBVs do increase the luminosity, so much so that they have been tagged supernova impostors, and may be a different type of event.

These massive evolved stars are unstable due to their high luminosity and position above the instability strip, and they exhibit slow but sometimes large photometric and spectroscopic changes due to high mass loss and occasional larger eruptions, combined with secular variation on an observable timescale.

Gamma Cassiopeiae (γ Cas) variables are non-supergiant fast-rotating B class emission line-type stars that fluctuate irregularly by up to 1.5 magnitudes (4 fold change in luminosity) due to the ejection of matter at their equatorial regions caused by the rapid rotational velocity.

Variability scales ranges from days, close to the orbital period and sometimes also with eclipses, to years as sunspot activity varies.

A supernova can briefly emit as much energy as an entire galaxy, brightening by more than 20 magnitudes (over one hundred million times brighter).

Also unlike supernovae, novae ignite from the sudden onset of thermonuclear fusion, which under certain high pressure conditions (degenerate matter) accelerates explosively.

These symbiotic binary systems are composed of a red giant and a hot blue star enveloped in a cloud of gas and dust.

Stars with sizeable sunspots may show significant variations in brightness as they rotate, and brighter areas of the surface are brought into view.

Stars with ellipsoidal shapes may also show changes in brightness as they present varying areas of their surfaces to the observer.

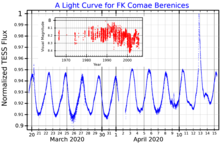

A possible explanation for the rapid rotation of FK Comae stars is that they are the result of the merger of a (contact) binary.

Alpha2 Canum Venaticorum (α2 CVn) variables are main-sequence stars of spectral class B8–A7 that show fluctuations of 0.01 to 0.1 magnitudes (1% to 10%) due to changes in their magnetic fields.

Stars in this class exhibit brightness fluctuations of some 0.1 magnitude caused by changes in their magnetic fields due to high rotation speeds.

Beta Lyrae (β Lyr) variables are extremely close binaries, named after the star Sheliak.

W Serpentis is the prototype of a class of semi-detached binaries including a giant or supergiant transferring material to a massive more compact star.

They are characterised, and distinguished from the similar β Lyr systems, by strong UV emission from accretions hotspots on a disc of material.