Vector field

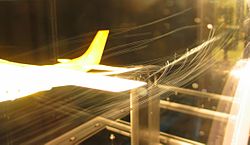

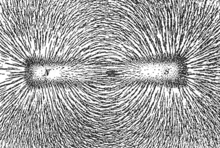

Vector fields are often used to model, for example, the speed and direction of a moving fluid throughout three dimensional space, such as the wind, or the strength and direction of some force, such as the magnetic or gravitational force, as it changes from one point to another point.

The elements of differential and integral calculus extend naturally to vector fields.

When a vector field represents force, the line integral of a vector field represents the work done by a force moving along a path, and under this interpretation conservation of energy is exhibited as a special case of the fundamental theorem of calculus.

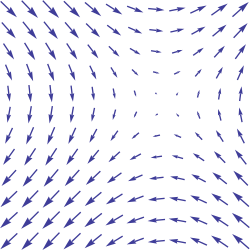

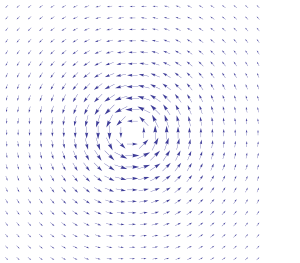

Vector fields can usefully be thought of as representing the velocity of a moving flow in space, and this physical intuition leads to notions such as the divergence (which represents the rate of change of volume of a flow) and curl (which represents the rotation of a flow).

A vector field is a special case of a vector-valued function, whose domain's dimension has no relation to the dimension of its range; for example, the position vector of a space curve is defined only for smaller subset of the ambient space.

Likewise, n coordinates, a vector field on a domain in n-dimensional Euclidean space

can be represented as a vector-valued function that associates an n-tuple of real numbers to each point of the domain.

This representation of a vector field depends on the coordinate system, and there is a well-defined transformation law (covariance and contravariance of vectors) in passing from one coordinate system to the other.

Vector fields are often discussed on open subsets of Euclidean space, but also make sense on other subsets such as surfaces, where they associate an arrow tangent to the surface at each point (a tangent vector).

More generally, vector fields are defined on differentiable manifolds, which are spaces that look like Euclidean space on small scales, but may have more complicated structure on larger scales.

[2] The reason for this notation is that a vector field determines a linear map from the space of smooth functions to itself,

Thus, suppose that (x1, ..., xn) is a choice of Cartesian coordinates, in terms of which the components of the vector V are

and suppose that (y1,...,yn) are n functions of the xi defining a different coordinate system.

A similar transformation law characterizes vector fields in physics: specifically, a vector field is a specification of n functions in each coordinate system subject to the transformation law (1) relating the different coordinate systems.

Since orthogonal transformations are actually rotations and reflections, the invariance conditions mean that vectors of a central field are always directed towards, or away from, 0; this is an alternate (and simpler) definition.

Intuitively this is summing up all vector components in line with the tangents to the curve, expressed as their scalar products.

Given a vector field V and a curve γ, parametrized by t in [a, b] (where a and b are real numbers), the line integral is defined as

To show vector field topology one can use line integral convolution.

The divergence at a point represents the degree to which a small volume around the point is a source or a sink for the vector flow, a result which is made precise by the divergence theorem.

This intuitive description is made precise by Stokes' theorem.

The index of the vector field as a whole is defined when it has just finitely many zeroes.

For a vector field on a compact manifold with finitely many zeroes, the Poincaré-Hopf theorem states that the vector field’s index is the manifold’s Euler characteristic.

In recent decades many phenomenological formulations of irreversible dynamics and evolution equations in physics, from the mechanics of complex fluids and solids to chemical kinetics and quantum thermodynamics, have converged towards the geometric idea of "steepest entropy ascent" or "gradient flow" as a consistent universal modeling framework that guarantees compatibility with the second law of thermodynamics and extends well-known near-equilibrium results such as Onsager reciprocity to the far-nonequilibrium realm.

are called integral curves or trajectories (or less commonly, flow lines) of the vector field

In two or three dimensions one can visualize the vector field as giving rise to a flow on

Typical applications are pathline in fluid, geodesic flow, and one-parameter subgroups and the exponential map in Lie groups.

is called complete if each of its flow curves exists for all time.

[6] In particular, compactly supported vector fields on a manifold are complete.

The Lie bracket has a simple definition in terms of the action of vector fields on smooth functions

Replacing vectors by p-vectors (pth exterior power of vectors) yields p-vector fields; taking the dual space and exterior powers yields differential k-forms, and combining these yields general tensor fields.