Euclidean vector

The mathematical representation of a physical vector depends on the coordinate system used to describe it.

Other vector-like objects that describe physical quantities and transform in a similar way under changes of the coordinate system include pseudovectors and tensors.

Working in a Euclidean plane, he made equipollent any pair of parallel line segments of the same length and orientation.

Like Bellavitis, Hamilton viewed vectors as representative of classes of equipollent directed segments.

As complex numbers use an imaginary unit to complement the real line, Hamilton considered the vector v to be the imaginary part of a quaternion:[10] The algebraically imaginary part, being geometrically constructed by a straight line, or radius vector, which has, in general, for each determined quaternion, a determined length and determined direction in space, may be called the vector part, or simply the vector of the quaternion.Several other mathematicians developed vector-like systems in the middle of the nineteenth century, including Augustin Cauchy, Hermann Grassmann, August Möbius, Comte de Saint-Venant, and Matthew O'Brien.

Grassmann's 1840 work Theorie der Ebbe und Flut (Theory of the Ebb and Flow) was the first system of spatial analysis that is similar to today's system, and had ideas corresponding to the cross product, scalar product and vector differentiation.

His 1867 Elementary Treatise of Quaternions included extensive treatment of the nabla or del operator ∇.

Josiah Willard Gibbs, who was exposed to quaternions through James Clerk Maxwell's Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, separated off their vector part for independent treatment.

In physics and engineering, a vector is typically regarded as a geometric entity characterized by a magnitude and a relative direction.

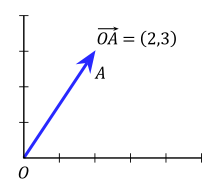

For instance, the velocity 5 meters per second upward could be represented by the vector (0, 5) (in 2 dimensions with the positive y-axis as 'up').

Examples of quantities that have magnitude and direction, but fail to follow the rules of vector addition, are angular displacement and electric current.

This coordinate representation of free vectors allows their algebraic features to be expressed in a convenient numerical fashion.

In the geometrical and physical settings, it is sometimes possible to associate, in a natural way, a length or magnitude and a direction to vectors.

One physical example comes from thermodynamics, where many quantities of interest can be considered vectors in a space with no notion of length or angle.

The vectors described in this article are a very special case of this general definition, because they are contravariant with respect to the ambient space.

Vectors are usually shown in graphs or other diagrams as arrows (directed line segments), as illustrated in the figure.

A circle with a dot at its centre (Unicode U+2299 ⊙) indicates a vector pointing out of the front of the diagram, toward the viewer.

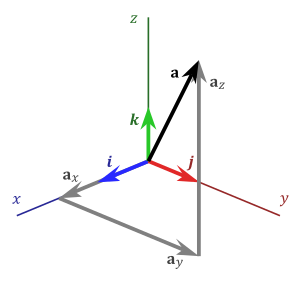

These have the intuitive interpretation as vectors of unit length pointing up the x-, y-, and z-axis of a Cartesian coordinate system, respectively.

The latter two choices are more convenient for solving problems which possess cylindrical or spherical symmetry, respectively.

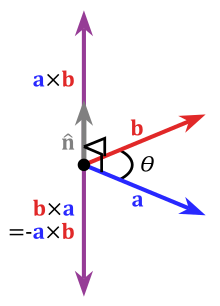

where θ is the measure of the angle between a and b, and n is a unit vector perpendicular to both a and b which completes a right-handed system.

First, the absolute value of the box product is the volume of the parallelepiped which has edges that are defined by the three vectors.

In such a case it is necessary to develop a method to convert between bases so the basic vector operations such as addition and subtraction can be performed.

One way to express u, v, w in terms of p, q, r is to use column matrices along with a direction cosine matrix containing the information that relates the two bases.

Equal length of vectors of different dimension has no particular significance unless there is some proportionality constant inherent in the system that the diagram represents.

An alternative characterization of Euclidean vectors, especially in physics, describes them as lists of quantities which behave in a certain way under a coordinate transformation.

Similarly, if the reference axes were stretched in one direction, the components of the vector would reduce in an exactly compensating way.

Examples of contravariant vectors include displacement, velocity, electric field, momentum, force, and acceleration.

A transformation that switches right-handedness to left-handedness and vice versa like a mirror does is said to change the orientation of space.

If the world is reflected in a mirror which switches the left and right side of the car, the reflection of this angular velocity vector points to the right, but the actual angular velocity vector of the wheel still points to the left, corresponding to the minus sign.

Other examples of pseudovectors include magnetic field, torque, or more generally any cross product of two (true) vectors.