Natural dye

Throughout history, people have dyed their textiles using common, locally available materials, but scarce dyestuffs that produced brilliant and permanent colors such as the natural invertebrate dyes Tyrian purple and crimson kermes became highly prized luxury items in the ancient and medieval world.

[4] Plant-based dyes such as woad (Isatis tinctoria), indigo, saffron, and madder were important trade goods in the economies of Asia, Africa and Europe.

[5] Western consumers have become more concerned about the health and environmental impact of synthetic dyes—which require the use of toxic fossil fuel byproducts for their production—in manufacturing and there is a growing demand for products that use natural dyes.

The types of natural dyes currently popular with craft dyers and the global fashion industry include:[6] Colors in the "ruddy" range of reds, browns, and oranges are the first attested colors in a number of ancient textile sites ranging from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age across the Levant, Egypt, Mesopotamia and Europe, followed by evidence of blues and then yellows, with green appearing somewhat later.

[14] His contributions to refining the dyeing process and his theories on color brought much praise by the well known poet and artist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Additional modifiers may be used during or after dying to protect fibre structure, shift pH to achieve different color results, or for any number of other desirably outcomes.

The Chinese ladao process is dated to the 10th century; other traditional techniques include tie-dye, batik, Rōketsuzome, katazome, bandhani and leheria.

[19] Some mordants and some dyestuffs produce strong odours, and the process of dyeing often depends on a good supply of fresh water, storage areas for bulky plant materials, vats which can be kept heated (often for days or weeks) along with the necessary fuel, and airy spaces to dry the dyed textiles.

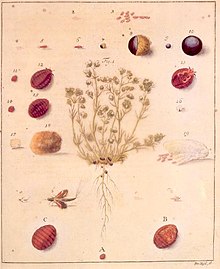

[21] Madder and related plants of the genus Rubia are native to many temperate zones around the world, and were already used as sources of good red dye in prehistory.

In the Philippines, red dye was obtained from noni (Morinda citrifolia) roots, sapang (sappanwood), katuray (Sesbania grandiflora), and narra wood (Pterocarpus spp.

[32] In Japan, dyers have mastered the technique of producing a bright red to orange-red dye (known as carthamin) from the dried florets of safflower (Carthamus tinctorius).

An extract made from plums that have been covered with soot and fumigated in a smoking pit for 24 hours, followed by a drying period of one month in the sun, is then used as a color fixing mordant.

[36] Yellow dyes are "about as numerous as red ones",[37] and can be extracted from saffron, pomegranate rind, turmeric, safflower, onion skins, and a number of weedy flowering plants.

[37][38] Limited evidence suggests the use of weld (Reseda luteola), also called mignonette or dyer's rocket[39] before the Iron Age,[37] but it was an important dye of the ancient Mediterranean and Europe and is indigenous to England.

[41] Navajo artists create yellow dyes from small snake-weed, brown onion skins, and rubber plant (Parthenium incanum).

[42] Woolen cloth mordanted with alum and dyed yellow with dyer's greenweed was overdyed with woad and, later, indigo, to produce the once-famous Kendal green.

In the Philippines, blue to indigo colors were also obtained from Indigofera tinctoria and related species, known under common names including tarum, dagum, tayum.

Other indigo-bearing dye plants include dyer's knotweed (Polygonum tinctorum) from Japan and the coasts of China, and the West African shrub Lonchocarpus cyanescens.

[29] Purples can also be derived from lichens, and from the berries of White Bryony from the northern Rocky Mountain states and mulberry (morus nigra) (with an acid mordant).

Juniper, Juniperus monosperma, ashes provide brown and yellow dyes for Navajo people,[31] as do the hulls of wild walnuts (Juglans major).

[50] Khaki, which translates a Hindustani word signifying "soil-colored", was introduced into British uniforms in India, which were dyed locally with a dye prepared from the native mazari palm Nannorrhops.

[29] Navajo weavers create black from mineral yellow ochre mixed with pitch from the piñon tree(Pinus edulis) and the three-leaved sumac (Rhus trilobata).

Swedish and American mycologists, building upon Rice's research, have discovered sources for true blues (Sarcodon squamosus) and mossy greens (Hydnellum geogenium).

Tyrian purple retained its place as the premium dye of Europe until it was replaced "in status and desirability"[55] by the rich crimson reds and scarlets of the new silk-weaving centers of Italy, colored with kermes.

[58] Woollens were frequently dyed in the fleece with woad and then piece-dyed in kermes, producing a wide range colors from blacks and grays through browns, murreys, purples, and sanguines.

[58] By the 14th and early 15th century, brilliant full grain kermes scarlet was "by far the most esteemed, most regal" color for luxury woollen textiles in the Low Countries, England, France, Spain and Italy.

[64][65] The origins of the trend for somber colors are elusive, but are generally attributed to the growing influence of Spain and possibly the importation of Spanish merino wools.

The trend spread in the next century: the Low Countries, German states, Scandinavia, England, France, and Italy all absorbed the sobering and formal influence of Spanish dress after the mid-1520s.

[67] Scientists continued to search for new synthetic dyes that would be effective on cellulose fibres like cotton and linen, and that would be more colorfast on wool and silk than the early anilines.

The European Union, for example, has encouraged Indonesian batik cloth producers to switch to natural dyes to improve their export market in Europe.