Venezuelan crisis of 1895

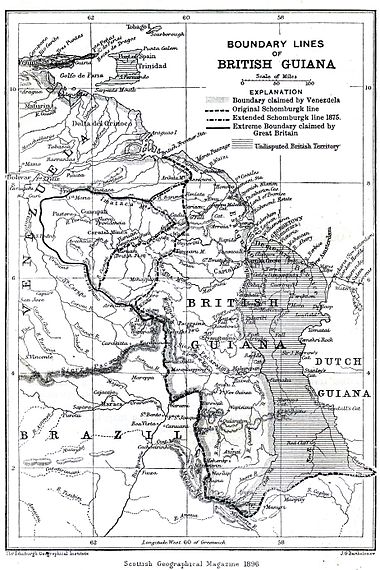

As the dispute became a crisis, the key issue became Britain's refusal to include in the proposed international arbitration the territory east of the "Schomburgk Line", which a surveyor had drawn half-a-century earlier as a boundary between Venezuela and the former Dutch territory ceded by the Dutch in the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, later part of British Guiana.

[2] The dispute had become a diplomatic crisis in 1895 when a lobbyist for Venezuela William Lindsay Scruggs sought to argue that British behaviour over the issue violated the 1823 Monroe Doctrine and used his influence in Washington, DC, to pursue the matter.

US President Grover Cleveland adopted a broad interpretation of the Doctrine that forbade new European colonies but also declared an American interest in any matter in the hemisphere.

[8] Over the course of the 19th century, Britain and Venezuela had proved no more able to reach an agreement until matters came to a head in 1895, after seven years of severed diplomatic relations.

The basis of the discussions between Venezuela and the United Kingdom lay in Britain's advocacy of a particular division of the territory deriving from a mid-19th-century survey that it had commissioned.

That survey originated with German naturalist Robert Schomburgk's four-year expedition for the Royal Geographical Society in 1835 to 1839, which resulted in a sketch of the territory with a line marking what he believed to be the western boundary claimed by the Dutch.

The dispute went unmentioned for many years until gold was discovered in the region, which disrupted relations between the United Kingdom and Venezuela.

[9] In October 1886, Britain declared the line to be the provisional frontier of British Guiana, and in February 1887 Venezuela severed diplomatic relations.

[citation needed] The mine at El Callao, started in 1871, was once one of the richest in the world, and the goldfields as a whole saw over a million ounces exported between 1860 and 1883.

[9] Scruggs, a former US ambassador to Colombia and Venezuela, was recruited in 1893 by the Venezuelan government to operate on its behalf in Washington D.C. as a lobbyist and legal attache.

[15] On April 27, 1895, the Royal Navy occupied the Nicaraguan port of Corinto, after a number of British subjects, including the vice-consul, had been seized during disturbances, shortly after the former protectorate of the Mosquito Coast had been incorporated into Nicaragua.

"[9]By 17 December 1895, Cleveland delivered an address to the United States Congress reaffirming the Monroe Doctrine and its relevance to the dispute.

[9] The address asked Congress to fund a commission to study the boundaries between Venezuela and British Guiana, and declared it the duty of the United States "to resist by every means in its power as a willful aggression upon its rights and interests" any British attempt to exercise jurisdiction over territory the United States judged Venezuelan.

"[19] In January 1896, the British government decided in effect to recognise the US right to intervene in the boundary dispute and accepted arbitration in principle without insisting on the Schomburgk line as a basis for negotiation.

[26] Britain's key argument was that prior to Venezuela's independence, Spain had not taken effective possession of the disputed territory and said that the local Indians had had alliances with the Dutch, which gave them a sphere of influence that the British acquired in 1814.

[30] With the Treaty of Washington, Great Britain and Venezuela both agreed that the arbitral ruling in Paris would be a "full, perfect, and final settlement"[31] (Article XIII) to the border dispute.

The first deviation from the Schomburgk line was that Venezuela's territory included Barima Point at the mouth of the Orinoco, giving it undisputed control of the river and thus the ability to levy duties on Venezuelan commerce.

[34] Though the Venezuelans were keenly disappointed with the outcome, they honoured their counsel for their efforts (their delegation's Secretary, Severo Mallet-Prevost, received the Order of the Liberator in 1944), and abided by the award.

[34] The Anglo-Venezuelan boundary dispute asserted for the first time a more outward-looking American foreign policy, particularly in the Americas, marking the United States as a world power.

US Secretary of State Richard Olney in January 1897 negotiated an arbitration treaty with the British diplomat Julian Pauncefote.

However, half a century later, the publication of an alleged political deal between Russia and Britain led Venezuela to reassert its claims.

That reopened the issues, with Mallet-Prevost surmising a political deal between Russia and Britain from the subsequent private behaviour of the judges.

Mallet-Prevost said that the American judges and Venezuelan counsel were disgusted at the situation and considered the 3-2 option with a strongly-worded minority opinion but ultimately went along with Martens to avoid depriving Venezuela of valuable territory to which it was entitled.

* The extreme border claimed by Britain

* The current boundary (roughly) and

* The extreme border claimed by Venezuela