Vietnamese language

In 1850, British lawyer James Richardson Logan detected striking similarities between the Korku language in Central India and Vietnamese.

Later, in 1920, French-Polish linguist Jean Przyluski found that Mường is more closely related to Vietnamese than other Mon–Khmer languages, and a Viet–Muong subgrouping was established, also including Thavung, Chut, Cuoi, etc.

[19] Borrowed vocabulary indicates early contact with speakers of Tai languages in the last millennium BC, which is consistent with genetic evidence from Dong Son culture sites.

[20] At this time, Vietic groups began to expand south from the Red River Delta and into the adjacent uplands, possibly to escape Chinese encroachment.

[21] The northern Vietic varieties thus became part of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, in which languages from genetically unrelated families converged toward characteristics such as isolating morphology and similar syllable structure.

[28] Vietic languages were confined to the northern third of modern Vietnam until the "southward advance" (Nam tiến) from the late 15th century.

After France invaded Vietnam in the late 19th century, French gradually replaced Literary Chinese as the official language in education and government.

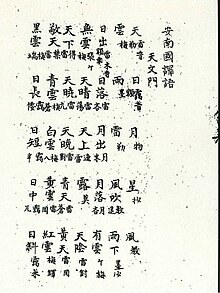

The sources for the reconstruction of Old Vietnamese are Nom texts, such as the 12th-century/1486 Buddhist scripture Phật thuyết Đại báo phụ mẫu ân trọng kinh ("Sūtra explained by the Buddha on the Great Repayment of the Heavy Debt to Parents"),[42] old inscriptions, and a late 13th-century (possibly 1293) Annan Jishi glossary by Chinese diplomat Chen Fu (c. 1259 – 1309).

[46] This conveys the transformation of the Vietnamese lexicon from sesquisyllabic to fully monosyllabic under the pressure of Chinese linguistic influence, characterized by linguistic phenomena such as the reduction of minor syllables; loss of affixal morphology drifting towards analytical grammar; simplification of major syllable segments, and the change of suprasegment instruments.

The language also has three clusters at the beginning of syllables, which have since disappeared: Most of the unusual correspondences between spelling and modern pronunciation are explained by Middle Vietnamese.

Note in particular: De Rhodes's orthography also made use of an apex diacritic on o᷃ and u᷃ to indicate a final labial-velar nasal /ŋ͡m/, an allophone of /ŋ/ that is peculiar to the Hanoi dialect to the present day.

Additionally, as immigration to the United States following the Vietnam war was primarily driven due to political reasons, the Southern Vietnamese dialect was initially strongly linked to social identity.

It is also spoken by the Jing people traditionally residing on three islands (now joined to the mainland) off Dongxing in southern Guangxi Province, China.

In addition, in the diphthongs [āj] and [āːj] the letters y and i also indicate the pronunciation of the main vowel: ay = ă + /j/, ai = a + /j/.

In some cases, they are based on their Middle Vietnamese pronunciation; since that period, ph and kh (but not th) have evolved from aspirated stops into fricatives (like Greek phi and chi), while d and gi have collapsed and converged together (into /z/ in the north and /j/ in the south).

However, according to linguist John Phan, “Annamese Middle Chinese” was already used and spoken in the Red River Valley by the 1st century CE, and its vocabulary significantly fused with the co-existing Proto-Viet-Muong language, the immediate ancestor of Vietnamese.

The Vietnamese term for steering wheel is "vô lăng", a partial derivation from the French volant directionnel.

This vocabulary includes words representative of Japanese culture, such as kimono, sumo, samurai, and bonsai from modified Hepburn romanisation.

Additionally, in the southern provinces of Vietnam, the term xí ngầu can be used to refer to dice, which may have derived from a Cantonese or Teochew idiom, "xập xí, xập ngầu" (十四, 十五, Sino-Vietnamese: thập tứ, thập ngũ), literally "fourteen, fifteen" to mean 'uncertain'.

Some believe that incorporating teenspeak or internet slang in daily conversation among teenagers will affect the formality and cadence of their general speech.

[92][93] The script also represents additional phonemes using ten digraphs (ch, gh, gi, kh, ng, nh, ph, qu, th, and tr) and a single trigraph (ngh).

[94] Starting from the late 19th century, the Vietnamese alphabet (chữ Quốc ngữ or 'national language script') gradually expanded from its initial usage in Christian writing to become more popular among the general public.

The romanised script became predominant over the course of the early 20th century, when education became widespread and a simpler writing system was found to be more expedient for teaching and communication with the general population.

Vietnamese written with the alphabet became required for all public documents in 1910 by issue of a decree by the French Résident Supérieur of the protectorate of Tonkin.

Nevertheless, chữ Hán was still in use during the French colonial period and as late as World War II was still featured on banknotes,[95][96] but fell out of official and mainstream use shortly thereafter.

Priests of the Jing minority in China (descendants of 16th-century migrants from Vietnam) use songbooks and scriptures written in chữ Nôm in their ceremonies.

The Tale of Kiều is an epic narrative poem by the celebrated poet Nguyễn Du, (阮攸), which is often considered the most significant work of Vietnamese literature.

[l] The North-Central and the Central regional varieties, which have a significant number of vocabulary differences, are generally less mutually intelligible to Northern and Southern speakers.

After the Geneva Accords of 1954, which called for the temporary division of the country, about a million northerners (mainly from Hanoi, Haiphong, and the surrounding Red River Delta areas) moved south (mainly to Saigon and heavily to Biên Hòa and Vũng Tàu and the surrounding areas) as part of Operation Passage to Freedom.

More recently, the growth of the free market system has resulted in increased interregional movement and relations between distant parts of Vietnam through business and travel.