Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis

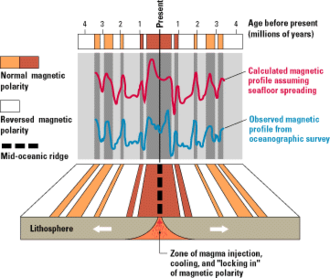

It states that the Earth's oceanic crust acts as a recorder of reversals in the geomagnetic field direction as seafloor spreading takes place.

[3] Geophysicist Frederick John Vine and the Canadian geologist Lawrence W. Morley independently realized that if Hess's seafloor spreading theory was correct, then the rocks surrounding the mid-oceanic ridges should show symmetric patterns of magnetization reversals using newly collected magnetic surveys.

[4] Both of Morley's letters to Nature (February 1963) and Journal of Geophysical Research (April 1963) were rejected, hence Vine and his PhD adviser at Cambridge University, Drummond Hoyle Matthews, were first to publish the theory in September 1963.

[5][6] Some colleagues were skeptical of the hypothesis because of the numerous assumptions made—seafloor spreading, geomagnetic reversals, and remanent magnetism—all hypotheses that were still not widely accepted.

Further evidence for this hypothesis came from Allan V. Cox and colleagues (1964) when they measured the remanent magnetization of lavas from land sites.

[8][9] Walter C. Pitman and J. R. Heirtzler offered further evidence with a remarkably symmetric magnetic anomaly profile from the Pacific-Antarctic Ridge.

The component of the vector that effects the anomaly is at a maximum when the ridge is aligned east-west and the magnetic profile crossing is north-south.

Early in the history of investigating the hypothesis only a short record of geomagnetic field reversals was available for studies of rocks on land.