Our Lady of Guadalupe

Juan Diego experienced a vision of a young woman at a place called the Hill of Tepeyac, which later became part of Villa de Guadalupe, in a suburb of Mexico City.

What is purported by some to be the earliest mention of the miraculous apparition of the Virgin is a page of parchment, the Codex Escalada from 1548, which was discovered in 1995 and, according to investigative analysis, dates from the sixteenth century.

[16][17] A more complete early description of the apparition occurs in a 16-page manuscript called the Nican mopohua, which has been reliably dated in 1556 and was acquired by the New York Public Library in 1880.

[23] The written record suggests the Catholic clergy in 16th century Mexico were deeply divided as to the orthodoxy of the native beliefs springing up around the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, with the Franciscan order (who then had custody of the chapel at Tepeyac) being strongly opposed to the outside groups, while the Dominicans supported it.

In a 1556 sermon Montúfar commended popular devotion to "Our Lady of Guadalupe", referring to a painting on cloth (the tilma) in the chapel of the Virgin Mary at Tepeyac, where certain miracles had also occurred.

Days later, Fray Francisco de Bustamante, local head of the Franciscan order, delivered a sermon denouncing the native belief and believers.

[27][28] A document called "Informaciones 1556" and published in 1888 states that on September 8, 1556, the feast of the Nativity of Mary, at the end of the sermon that Bustamante gave in the chapel of San José in the convent of San Francisco in Mexico, Bustamante attacked Archbishop Montúfar for having, according to the former, encouraged a devotion that had arisen around an image “painted yesterday by the Indian Marcos.”[29][30][31] Prof. Jody Brant Smith, referring to Philip Serna Callahan's examination of the tilma using infrared photography in 1979, wrote: "if Marcos did, he apparently did so without making a preliminary sketches – in itself then seen as a near-miraculous procedure... Cipac may well have had a hand in painting the Image, but only in painting the additions, such as the angel and moon at the Virgin's feet.

[36]Sahagún's criticism of the indigenous group seems to have stemmed primarily from his concern about a syncretistic application of the native name Tonantzin to the Catholic Virgin Mary.

[38] Another account is the Codex Escalada, dating from the sixteenth century, a sheet of parchment recording apparitions of the Virgin Mary and the figure of Juan Diego, which reproduces the glyph of Antonio Valeriano alongside the signature of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún.

[18] A manuscript version of the Nican Mopohua, which is now held by the New York Public Library,[41] appears to be dated to c. 1556, and may have been the original work by Valeriano, as that was used by Laso in composing the Huei tlamahuiçoltica.

Because of the Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666 in the year 1754, the Sacred Congregation of Rites confirmed the true and valid value of the apparitions, and granted celebrating Mass and Office for the then Catholic version of the feast of Guadalupe on December 12.

In 1996 the 83-year-old abbot of the Basilica of Guadalupe, Guillermo Schulenburg, was forced to resign following an interview published in the Catholic magazine Ixthus, in which he was quoted as saying that Juan Diego was "a symbol, not a reality", and that his canonization would be the "recognition of a cult.

"[61] In 1883 Joaquín García Icazbalceta, historian and biographer of Zumárraga, in a confidential report on the Lady of Guadalupe for Bishop Labastida, had been hesitant to support the story of the vision.

[16][pages needed][63] Some scholars remained unconvinced, one describing the discovery of the Codex as "rather like finding a picture of St. Paul's vision of Christ on the road to Damascus, drawn by St. Luke and signed by St.

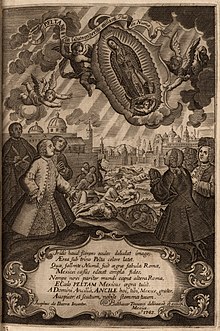

[68] The theory promoting the Spanish origin of the name says that: The image of Our Lady of Guadalupe is of a life-sized, dark-haired, olive-skinned young woman, standing with her head slightly inclined to her right, eyes downcast, and her hands held before her in prayer.

[75] The iconography of the Virgin is fully Catholic:[76] Miguel Sánchez, the author of the 1648 tract Imagen de la Virgen María, described her as the Woman of the Apocalypse from the New Testament's Revelation 12:1, "clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars."

The painters unanimously agreed that it was "impossible that any artist could paint and work something so beautiful, clean, and well-formed on a fabric which is as rough as is the tilma",[86][85] and that the image must therefore be miraculous.

[94] In 1982, Guillermo Schulenburg, abbot of the basilica, hired José Sol Rosales of the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura to study the image.

[102] In 1810, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla initiated the bid for Mexican independence with his Grito de Dolores, with the cry "Death to the Spaniards and long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!"

"[100] After Hidalgo's death, leadership of the revolution fell to a mestizo priest named José María Morelos, who led insurgent troops in the Mexican south.

[100]Simón Bolívar noticed the Guadalupan theme in these uprisings, and shortly before Morelos's execution in 1815 wrote: "the leaders of the independence struggle have put fanaticism to use by proclaiming the famous Virgin of Guadalupe as the queen of the patriots, praying to her in times of hardship and displaying her on their flags... the veneration for this image in Mexico far exceeds the greatest reverence that the shrewdest prophet might inspire.

Though Zapata's rebel forces were primarily interested in land reform—"tierra y libertad" ('land and liberty') was the slogan of the uprising—when his peasant troops penetrated Mexico City, they carried Guadalupan banners.

[103] More recently, the contemporary Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) named their "mobile city" in honor of the Virgin: it is called Guadalupe Tepeyac.

"[112] Nobel Literature laureate Octavio Paz wrote in 1974 that "The Mexican people, after more than two centuries of experiments and defeats, have faith only in the Virgin of Guadalupe and the National Lottery.

Over the Friday and Saturday of December 11 to 12, 2009, a record number of 6.1 million pilgrims visited the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City to commemorate the anniversary of the apparition.

[1] In addition, due to the growth of Hispanic communities in the United States, religious imagery of Our Lady of Guadalupe has started appearing in some Lutheran, Anglican, and Methodist churches.

[116][117][118] Due to her association as a crusader of social justice, the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe has been utilized as a symbol across regions to advance political movements and mobilize the masses.

In fact, the first president of the Mexican republic, José Miguel Ramón Adaucto Fernández y Félix, who was heavily involved in Mexico's Independence war, changed his name as to Guadalupe Victoria as a sign of devotion.

[135] Similarly to Mexico's Independence movement, the famous pilgrimage in 1966 that drew national attention to the cause was lead under a banner with the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

For instance, Ester Hernandez's screen print titled Wanted (2010) and Consuelo Jimenez Underwood's Sacred Jump (1994) and Virgen de los Caminos (1994).