Virology

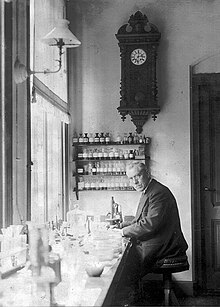

The identification of the causative agent of tobacco mosaic disease (TMV) as a novel pathogen by Martinus Beijerinck (1898) is now acknowledged as being the official beginning of the field of virology as a discipline distinct from bacteriology.

Louis Pasteur was unable to find a causative agent for rabies and speculated about a pathogen too small to be detected by microscopes.

[6] At the time it was thought that all infectious agents could be retained by filters and grown on a nutrient medium—this was part of the germ theory of disease.

[7] In 1898, the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck repeated the experiments and became convinced that the filtered solution contained a new form of infectious agent.

[8] He observed that the agent multiplied only in cells that were dividing, but as his experiments did not show that it was made of particles, he called it a contagium vivum fluidum (soluble living germ) and reintroduced the word virus.

Beijerinck maintained that viruses were liquid in nature, a theory later discredited by Wendell Stanley, who proved they were particulate.

[6] In the same year, Friedrich Loeffler and Paul Frosch passed the first animal virus, aphthovirus (the agent of foot-and-mouth disease), through a similar filter.

[12] By the end of the 19th century, viruses were defined in terms of their infectivity, their ability to pass filters, and their requirement for living hosts.

[14] Another breakthrough came in 1931 when the American pathologist Ernest William Goodpasture and Alice Miles Woodruff grew influenza and several other viruses in fertilised chicken eggs.

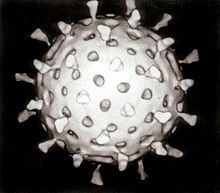

[17] The first images of viruses were obtained upon the invention of electron microscopy in 1931 by the German engineers Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll.

[18] In 1935, American biochemist and virologist Wendell Meredith Stanley examined the tobacco mosaic virus and found it was mostly made of protein.

Reverse transcriptase, the enzyme that retroviruses use to make DNA copies of their RNA, was first described in 1970 by Temin and David Baltimore independently.

[31] Many viruses were discovered using this technique and negative staining electron microscopy is still a valuable weapon in a virologist's arsenal.

For instance, herpes simplex viruses produce a characteristic "ballooning" of the cells, typically human fibroblasts.

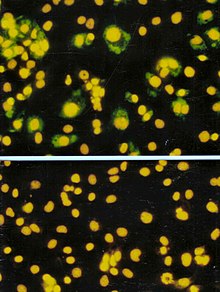

The antibodies are tagged with a dye that is luminescencent and when using an optical microscope with a modified light source, infected cells glow in the dark.

The so-called "home" or "self"-testing gadgets are usually lateral flow tests, which detect the virus using a tagged monoclonal antibody.

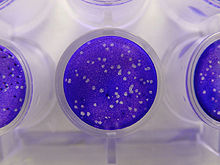

[50] Counting viruses (quantitation) has always had an important role in virology and has become central to the control of some infections of humans where the viral load is measured.

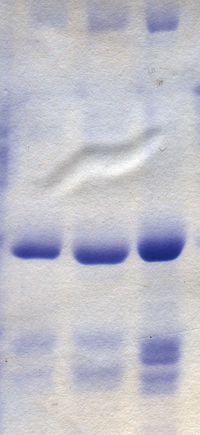

Like the plaque assay, host cell monolayers are infected with various dilutions of the virus sample and allowed to incubate for a relatively brief incubation period (e.g., 24–72 hours) under a semisolid overlay medium that restricts the spread of infectious virus, creating localized clusters (foci) of infected cells.

The FFA method typically yields results in less time than plaque or fifty-percent-tissue-culture-infective-dose (TCID50) assays, but it can be more expensive in terms of required reagents and equipment.

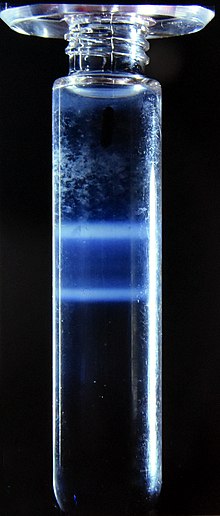

[62] Following differential centrifugation, virus suspensions often remain contaminated with debris that has the same sedimentation coefficient and are not removed by the procedure.

Caesium chloride is often used for these solutions as it is relatively inert but easily self-forms a gradient when centrifuged at high speed in an ultracentrifuge.

[68] At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic the availability of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA sequence enabled tests to be manufactured quickly.

[73] Bacteriophages, long known for their positive effects in the environment, are used in phage display techniques for screening proteins DNA sequences.

Recombination is not as common as reassortment in nature but it is a powerful tool in laboratories for studying the structure and functions of viral genes.

[83] In 1962, André Lwoff, Robert Horne, and Paul Tournier were the first to develop a means of virus classification, based on the Linnaean hierarchical system.

The system proposed by Lwoff, Horne and Tournier was initially not accepted by the ICTV because the small genome size of viruses and their high rate of mutation made it difficult to determine their ancestry beyond order.

[86] Starting in 2018, the ICTV began to acknowledge deeper evolutionary relationships between viruses that have been discovered over time and adopted a 15-rank classification system ranging from realm to species.

[88][89] The ICTV developed the current classification system and wrote guidelines that put a greater weight on certain virus properties to maintain family uniformity.

[90] As of 2021, 6 realms, 10 kingdoms, 17 phyla, 2 subphyla, 39 classes, 65 orders, 8 suborders, 233 families, 168 subfamilies, 2,606 genera, 84 subgenera, and 10,434 species of viruses have been defined by the ICTV.

Viral genomes may be single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds), RNA or DNA, and may or may not use reverse transcriptase (RT).