Viscoelasticity

Viscous materials, like water, resist both shear flow and strain linearly with time when a stress is applied.

Elastic materials strain when stretched and immediately return to their original state once the stress is removed.

[1] In the nineteenth century, physicists such as James Clerk Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann, and Lord Kelvin researched and experimented with creep and recovery of glasses, metals, and rubbers.

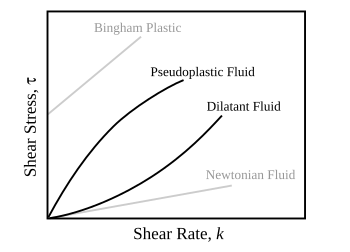

[1] Depending on the change of strain rate versus stress inside a material, the viscosity can be categorized as having a linear, non-linear, or plastic response.

[1] Many viscoelastic materials exhibit rubber like behavior explained by the thermodynamic theory of polymer elasticity.

Ligaments and tendons are viscoelastic, so the extent of the potential damage to them depends on both the rate of the change of their length and the force applied.

Since viscosity is the resistance to thermally activated plastic deformation, a viscous material will lose energy through a loading cycle.

Plastic deformation results in lost energy, which is uncharacteristic of a purely elastic material's reaction to a loading cycle.

where Viscoelasticity is studied using dynamic mechanical analysis, applying a small oscillatory stress and measuring the resulting strain.

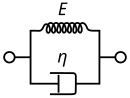

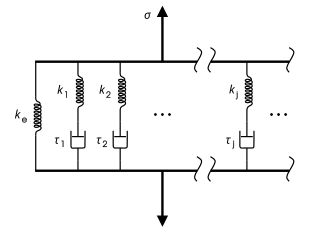

Viscoelastic behavior has elastic and viscous components modeled as linear combinations of springs and dashpots, respectively.

First, an elastic component occurs instantaneously, corresponding to the spring, and relaxes immediately upon release of the stress.

The Maxwell model for creep or constant-stress conditions postulates that strain will increase linearly with time.

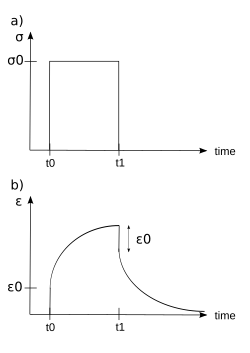

Upon application of a constant stress, the material deforms at a decreasing rate, asymptotically approaching the steady-state strain.

At constant stress (creep), the model is quite realistic as it predicts strain to tend to σ/E as time continues to infinity.

It is the simplest model that describes both the creep and stress relaxation behaviors of a viscoelastic material properly.

Due to molecular segments of different lengths with shorter ones contributing less than longer ones, there is a varying time distribution.

Non-linear viscoelastic constitutive equations are needed to quantitatively account for phenomena in fluids like differences in normal stresses, shear thinning, and extensional thickening.

[3] Necessarily, the history experienced by the material is needed to account for time-dependent behavior, and is typically included in models as a history kernel K.[12] The second-order fluid is typically considered the simplest nonlinear viscoelastic model, and typically occurs in a narrow region of materials behavior occurring at high strain amplitudes and Deborah number between Newtonian fluids and other more complicated nonlinear viscoelastic fluids.

[22] Because thermal motion is one factor contributing to the deformation of polymers, viscoelastic properties change with increasing or decreasing temperature.

In most cases, the creep modulus, defined as the ratio of applied stress to the time-dependent strain, decreases with increasing temperature.

Generally speaking, an increase in temperature correlates to a logarithmic decrease in the time required to impart equal strain under a constant stress.

For example, exposure of pressure sensitive adhesives to extreme cold (dry ice, freeze spray, etc.)

When subjected to a step constant stress, viscoelastic materials experience a time-dependent increase in strain.

, a viscoelastic material is loaded with a constant stress that is maintained for a sufficiently long time period.

If, on the other hand, it is a viscoelastic solid, it may or may not fail depending on the applied stress versus the material's ultimate resistance.

The testing can be done at constant strain rate, stress, or in an oscillatory fashion (a form of dynamic mechanical analysis).

[27] Shear rheometers are typically limited by edge effects where the material may leak out from between the two plates and slipping at the material/plate interface.

[28] Extensional rheometers are also limited by edge effects at the ends of the extensiometer and pressure differences between inside and outside the capillary.

Although this requires the use of different instruments, these techniques and apparatuses allow for the study of the extensional viscoelastic properties of materials such as polymer melts.

The Meissner-type rheometer, developed by Meissner and Hostettler in 1996, uses two sets of counter-rotating rollers to strain a sample uniaxially.