Visionary architecture

[1][4] Traditionally, the term visionary refers to a person who has visions or sees things that do not exist in the real world, such as a saint or someone who is mentally unbalanced.

[5] However, an article in Forbes noted, "Whereas ordinary architecture literally shapes the way in which we live, unrealized plans and models provide infrastructure for our collective imagination.

[2][7] Prominent modern and pre-modern visionary architects include Etienne-Louis Boullée, Peter Eisenman, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, Antonio Sant'Elia, and Lebbeus Woods.

In the 16th century, a Dutch painter and architect, Jan Vredeman de Vries, produced numerous engravings that portrayed new forms of architecture.

[12] Some visionary architects skipped the model process entirely, believing that drawing is "the highest form and clearest expression of architecture.

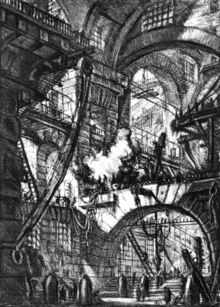

[10] Visionary architecture of the 18th century centered around projects of immense size that "defied both man's comprehension and his building techniques.

[14] Ledoux developed an entire master plan for Chaux, along with architectural drawings, elevations, and sections of various individual buildings.

[15] After the French Revolution ended his chance to become a palace architect, he worked as a civil servant, cartographer, surveyor, and draftsman.

[16] He was also an influential architectural theorist because he taught at the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées and elsewhere for fifty years.

[16] In his La Théorie Des Corps, he discussed the properties of geometric forms such as the cube, cylinder, pyramid, and sphere and their effect on the senses.

[1] Early 20th-century Visionary architecture is divided into three main movements: German expressionism, Italian futurism, and Russian constructivism.

[20] Russian constructivism also emerged after World War I, and leaned toward "openwork, pavilion-like structures with strident placards and public-address systems.

[19] One outstanding example of this style is the Vesnin brothers' design for the Palace of the Soviets, with its immense size and mechanization through projections at each level.

[19] In 1960, Arthur Drexler curated an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City that showcased the designs of visionary architects.

[1] The exhibition included architectural drawings of Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn, William Katavolos, Frederick John Kiesler, Hans Poelzig, Paolo Soleri, and Michael Webb.

[1] During this time, visionary architects tended to create designs that either anticipated the future or exaggerated and distorted existing structures.

[6] It included Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Ron Herron, and Michael Webb.

[6] Archigram's work was almost exclusively visionary; its only constructed designs were a swimming pool for Rod Stewart and a playground in Buckinghamshire.

[24] Peter Eisenman is a deconstructivist theorist who believes that architecture should be disharmonious or even nonfunctional because this would "make people think rather than feel".

[25] For example, House IV had a column that abutted the dining table and it was impossible to fit a double bed in the main bedroom because a glass strip ran through the center of the room.

[10] Finsterlin's architectural drawings are among the purest paper buildings ever developed and would require ingenious engineering to construct because his designs go against their form.

[26] One of her significant buildings is the Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, Ohio, essentially "a vertical series of cubes and voids".

[6] One writer notes, "Jonas's funnels question the assumption that urban residences ought to be refuges from the cities in which we live, and encourage us to consider more holistic options.

[30] His visionary architectural designs include floor plans of destroyed buildings and sketches of piles of sticks.

[3] When the paper architects won fifty competitions between 1981 and 1989, their visionary architecture began to be applauded within the Soviet Union.

[3] One work by the paper architects is Avvakumov’s Tower of Perestroika, an ironic reminiscence of Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International.

"[2] The Guardian noted that Woods created, "Dynamic compositions of splintered surfaces and twisted wiry forms, his fantastical scenes depicted alternative worlds, glimpses into a parallel universe writhing beneath the earth's crust.

"[2] Only one of his designs resulted in a physical building—the Light Pavilion within Steven Holl's vast complex of towers in Chengdu, China.