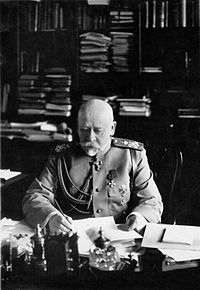

Vladimir Sukhomlinov

He encouraged official support for a major expansion of Aisenstein's work with the establishment of a series of experimental stations which were subsequently bought by the Ministry of War.

In this position, Sukhomlinov opposed training innovations that would have placed emphasis on infantry firepower against the use of sabers, lances and bayonets; stating that "I have not read a military manual for the last twenty-five years".

[8] Sukhomlinov held Grand Duke Nicolas, Guchkov and Polivanov responsible for his downfall and went fishing in Saimaa near Imatra, writing articles under the pseudonym Ostap Bondarenko and studying the Russo-Turkish War (1787–92).

[9] Maurice Paleologue, the last French ambassador to Imperial Russia, described Sukhomlinov as "intelligent, clever and cunning, obsequious towards the tsar and a friend of Rasputin—a man who has lost the habit of work—I know few men who inspire more distrust at first sight".

On the other hand, in Bayonets Before Bullets, Bruce W. Menning asserts that "There was no doubt that he remained committed to building Russia's defensive and offensive military power. ...

Though he has some criticism for the Minister, Menning credits him with simplifying and modernizing the structure of the Russian army corps, including the addition of a six aircraft detachment to each.

Norman Stone maintains that Sukhomlinov had "an extremely bad press" due to his autocratic style and accusations of corruption made by his enemies in the Imperial Duma and the army.

Stone details his position as the leader of an informal group of "praetorians" in the high ranks of the army: professional soldiers, often from lower- and middle-class backgrounds, with experience in and loyalty to the infantry.

[citation needed] Stone blames Sukhomlinov's failure to achieve more on problems of Russian development economics, and the resistance of the supposedly "technocratic" patrician faction.

Polivanov accused him of abuse of power, in relation with the divorce of his wife, corruption, depositing millions of rubles at the Deutsche Bank in Berlin, and high treason after some of his close associates had been convicted for espionage on behalf of Germany (c.q.

Sukhomlinov was rearrested during the February Revolution and locked up in the same cold and humid cell at Peter and Paul Fortress as two years before, in addition to his wife and Anna Vyrubova who were also imprisoned there.

[14] After the fall of the Russian Provisional Government, Sukhomlinov had in prison the company of all the former ministers, others were Alexei Khvostov, Purishkevich, and Stepan Petrovich Beletsky.

Highly critical of former colleagues, Sukhomlinov suggested that the Revolutions of 1917-1923 had occurred because the breakup of the League of the Three Emperors and the war prevented Russia and Germany from remaining united against liberal democracy.

Sukhomlinov lived the remainder of his life in extreme poverty in Berlin, where he was found dead from exposure to cold on a park bench one morning on 2 February 1926.